Audiovisual Scholarship and Experiments in Non-linear Film History

Tracy Cox-Stanton and John Gibbs

INTRODUCTION

In this essay, we want to consider how videographic forms provide an opportunity for inventive ways of making arguments, presenting evidence, and conveying analysis. While the audiovisual essay is increasingly legitimated within academia, there are still interesting questions to ask about its status as scholarship. Can the audiovisual essay do the same “work” as the written scholarly essay? Do audiovisual forms have any advantages in conveying an argument? Do they have particular limitations? Through a discussion of two of our own works, we suggest that indeed, the audiovisual essay offers a unique potential to convey the goals of scholarship through subjective, poetic, performative and filmic means. More precisely, as this essay will explore, videographic methods have the potential to enable novel approaches to film history.

Quite independently, both of us found ourselves pursuing non-linear forms in projects which reached publication within a few days of each other. John’s essay “Say, have you seen the Carioca?,” is “an experiment in non-linear, non-hierarchical approaches to film history,” and is organised around the motif of a mind map, which “charts journeys and relationships which are neither geographical nor chronological,” as its accompanying statement maintains. The subtitle to Tracy’s essay “Gesture in A Woman Under the Influence” is “a charting of relations,” a phrase meant to capture the video’s multiple and divergent lines of inquiry. Thus, while our work emerged from very different contexts and articulates divergent interests, it shares an ambition to use the possibilities presented by the audiovisual essay to engage with the complex entanglements of film history. Here we wish to reflect on those methods and consider how audiovisual expression might offer innovative ways of conveying the traditional goals of scholarship: staging a research question, developing an argument in response to that question, and presenting evidence to establish the value of that argument.

As Ian Garwood argues in [in]Transition, developing Christian Keathley’s critical categories (as Keathley himself does in his curatorial essay in the first issue of the journal), one should not underestimate the poetic in the explanatory, or works that integrate these two modes.[1] Keathley has argued more recently that the most compelling videos are those that “borrow the aesthetic force of the moving images and sounds that constitute their object of study … for their own critical work.”[2] We hope to further complicate the separation of the poetic and the explanatory, as we see great overlap between the modes, and celebrate videographic scholarship that imagines audiovisual strategies to convey the traditional and important work of scholarly explanation, argument, and analysis.

CONSTRUCTING A SCHOLARLY GAZE THROUGH VIDEO: OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

Tracy Cox-Stanton

“Gesture in A Woman Under the Influence” began in a way I imagine many scholarly investigations begin: with great personal investment channeled into some proper research questions. My investment was in the character of Mabel Longhetti, whose vibrance and eccentricity have always affected me deeply. I wanted to address the film in a way that kept this fictional character at the center of my study, without objectifying or dissecting her, and without subordinating her expression to the overarching discourse of John Cassavetes the auteur, or even of Gena Rowlands, the performer. I wanted to do justice to the film’s complex and loving treatment of Mabel and likewise cultivate a sympathetic gaze, but one that was critical and scholarly as well. The entry point for me—the locus for the appropriate research questions—was gesture. Thus my process, as with a traditional essay, began with research—in this case, a dive into the scholarly literature on gesture as well as more specific historical considerations of Swan Lake and of Charcot’s studies of hysteria.

In my research, I encountered a line from Lesley Stern’s essay “Putting on a Show, or the Ghostliness of Gesture” that seemed to articulate perfectly what had previously been only an intuition motivating my fixation on the Swan Lake references in A Woman Under the Influence. Stern writes,

This quote provided the anchor for my study as it not only articulated a theory of gesture but also suggested a non-hierarchical and intermedial method of expression that would allow for digressions, using gesture to smooth otherwise dizzying leaps through time and across media, from Cassavetes’ 1974 film to the Serpentine Dance filmed by the Kinetograph in 1894, from Anna Pavlova’s 1907 performance of “The Dying Swan” to Albert Londe’s 1880s “medical photography,” and from these images to Hollywood fan magazine articles and advertisements from the silent era into the 1970s.

Reading Georges Didi-Huberman’s Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, including its bounty of appendices, was enormously helpful in framing my research questions as well as shaping the structure and disposition of my video. While the book carefully develops its New Historical/Foucauldian argument about the invention of hysteria, it also uses first-person narration, figurative language and an unconventional structure to “retrace” Charcot’s world,[4] conveying an experiential sense of life at the Salpêtrière. In this way, it deviates from the typically “objective” academic study, acknowledging its own positioning and its construction of a gaze that is at the same time narrative, critical, and spectacular. The first chapter, “Spectacle” begins by asking “How might a relationship to pain already be projected, as it were, in our approach to works and images?”[5] This is precisely the kind of question I was contemplating in relation to the migrating gestures of Swan Lake, as well as in relation to my own application of audiovisual writing.

While my project began with the same process that would begin a written essay, it was obvious to me that my ideas would be best suited to a videographic expression because I recognized the video essay’s capacity to convey density, affect and ambiguity, refusing a singular, fixing narrative that might “explain away” Mabel’s predicament. While the traditional scholarly essay tends to necessitate a singular line of argument and repress the personal investment that underlies most research projects, the video essay is well suited to convey the author’s unique voice (often literally) and more easily permits multiple lines of inquiry. This is, of course, because the video essay has at its disposal not only the word-based language of scholarly critique, but also the expressive devices of filmmaking—montage, close-ups, color, movement, sound and sensation. These means of communication occur simultaneously (the image can suggest one thing, or more than one thing, while the sound suggests something else, for example), lending a multi-perspectival quality that can convey polysemous arguments with ease.

Gesture offered a suitable starting point for my experiment in a non-hierarchical film history that de-centered Cassavetes the director and suggested new entry points into the film. Gesture exceeds human agency and suggests, as Laura Mulvey and Lesley Stern have described, a ghostly actuation. This spectral quality is well suited for videographic expression since editing software can easily layer images to convey a density and complexity that would be difficult to achieve in writing. For example, in a short montage sequence that considers how the gestures of Swan Lake reverberate through film history, I layer and dissolve images from A Woman Under the Influence (1974), to Billy Elliot (2000), to The Red Shoes (1948), to Black Swan (2010), back to A Woman Under the Influence, and finally to Anna Pavlova’s 1907 performance of “The Dying Swan.” The result, I hope, is an argument that is felt as much as induced, aiming to defamiliarize (in the sense of ostranenie as discussed by Viktor Shklovsky) each individual example and encourage viewers to sense the accretion of a common theme. The editing uses graphic matches to link the gestures in these diverse films, illuminating the ways these scenes confront society’s wavering distinctions between the beautiful and the grotesque, the genius and the deviant.

While the video essay has many advantages over the traditional essay in conveying multivalent arguments that can re-purpose the emotional expressiveness of films, there are some scholarly tasks it is not well suited for. It is difficult to cite sources in a video essay, as the machinery of footnotes or parenthetical references disturbs the work’s artful flow. It is awkward to include footnotes visually, and nearly impossible to suggest them within a voice-over.[6] This is one reason I published the “script” of “Gesture in A Woman Under the Influence” alongside the video, so viewers can see where and what my voice is referencing; and I included an extensive bibliography at the end of the video, hoping to inventory all the sources that contributed to the video whether they “appear” in it or not. In some ways, my research process was perhaps more akin to the work of dramaturgy than traditional scholarship, since much of it doesn’t appear in the resultant work as it would in a written essay. Rather, it comprises a hidden foundation without which the work would collapse. Nevertheless, for me, this step of reading the work of other scholars and positioning my own thoughts in relation to theirs is central to the work of scholarship whether it manifests as a written or a videographic essay.

Another challenge for the scholarly video essay concerns its capacity for argument. The poetic ambiguity that I have framed here as an asset of videography can also be a shortcoming, as determining the argument is often a much more subjective matter for a video essay than it is for a written essay. Like films, video essays elicit varied responses in viewers whose preferences, sympathies, and emotional engagements inevitably impact the way they respond to the spectacular qualities of sound and image. Eric Faden’s 2008 “A Manifesto for Critical Media” identified the essay film as the key antecedent of the academic video essay and cited Godard’s definition of “research in the form of a spectacle.”[7] While I intentionally chose the essay film as a model for my videographic study of gesture in A Woman Under the Influence, I recognized that presenting my research in the form of a spectacle posed a number of challenges. By recirculating images of women from the Salpêtrière, I am, to some extent, participating in the spectacularization that I aim to critique. I hope that the images’ recontextualization and the rhythm and emotional register of the video convey my intent, but much is left to the viewer’s interpretation. Even when video essays aim to motivate filmic registers for scholarly purposes, their “knowledge effect” is inextricable from a particular sensibility and they are subject to the idiosyncratic reading of spectators who may or may not respond to that sensibility.

Finally, while my intention here has been to contrast the scholarly potentials of videographic approaches with that of the traditional academic essay, I think it is important to address the centrality of writing—good old-fashioned wrestling with words—to all scholarly endeavors. It is a mistake to see words as the enemy of a “poetic” video essay. After all, the term “poetic” originated to describe a particularly figurative use of words. When Viktor Shklovsky theorized ostranenie in “Art as Device,” his examples were from Tolstoy, not Eisenstein.[8] When academics speak of the video essay, it is understandable that we carry on about the potentials of expressing things videographically because that is what is new to us, but increasingly I realize that an audiovisual orientation nevertheless encompasses a close attention to words. In my experience, words in a video essay are subject to a strict economy and each one must do a lot of work. In “Gesture,” for example, the words I used to designate “chapters” were intended to function not only as traditional signposts to provide structure and clarity, but also to suggest some of the possibilities that reverberate through the video without quite rising to the surface.

While it’s indisputable that the traditional academic essay has evolved into a notably exegetic use of writing, there is nonetheless a solid history of scholars challenging that tradition. When I attended graduate school in the 1990s, academia was still under the heady and experimental sway of poststructuralism. The works of Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Hélène Cixous and others embraced the materiality of language and inspired the experimental methods of many scholars, including two of my own graduate professors, Robert B. Ray and Gregory Ulmer. At the same time, in Australia, a group of writers proposed the rubric of “fictocriticism” to describe their scholarly works that emphasized an embodied, first-person point of view, embraced figurative language and experimented with structure. Lesley Stern, whose essay on gesture inspired my video, is one of those writers and I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that the style of her writing influenced my work as much as its ideas about gesture. Likewise, as I mentioned in the beginning of this essay, Didi-Huberman’s book on Charcot is a poetic and performative work, interested as much in its “experience effect” as its “knowledge effect.”

Expressing my research videographically allowed me not only to write about a particular gaze, but to construct a scholarly gaze of my own. My intention was to create a point of view that short-circuits the easy objectification of the video’s aberrant bodies by recontextualizing them within scholarly considerations of gesture and within a broader history of society’s disciplining of the “feminine” body. This work of recontextualization is not unique to the video essay of course, as the same intention could just as easily motivate a written essay. In fact, that is what scholarly essays do—they raise questions about a topic, then reconsider those questions within the context of additional scholarly works and new ideas. But with the video essay, this recontextualization occurs through words, moving images and sounds, providing new opportunities and new challenges.

THE AUDIOVISUAL ESSAY AND INTERMEDIAL APPROACHES TO FILM HISTORY

John Gibbs

“Say, have you seen the Carioca?” was one of the outputs of an international research project which aimed to produce an intermedial history of Brazilian cinema and to explore intermediality as method for rethinking film history more generally. The IntermIdia project was a four-year collaboration between colleagues at the University of Reading and the Federal University of São Carlos, funded by a grant from the AHRC in the UK and FAPESP in Brazil. Though not envisaged in the original application, audiovisual forms of scholarship became an important aspect of our work; the project produced a number of audiovisual essays and an award-winning feature documentary. This development was due to a range of factors including, in the case of the essays, my participation in the inaugural NEH-funded Workshop, Scholarship in Sound and Image, at Middlebury College in 2015, the same year as the project began, and a timely call from [in]Transition for a special issue on Latin American Cinema which was responded to by two fellow project members. That the audiovisual essay is itself an intermedial form, and is thus particularly well suited to exploring these research questions, is also significant.

One of the stated objectives of our funding application was “to demonstrate the timeliness and advantages of the intermedial method over historiographies drawing on evolutionary chronologies and classical-modern or centre-periphery models, which inevitably lead to the privileging of certain styles and genres over others.” It continued, “The project will argue that the intermedial method can offer a non-linear and non-hierarchical, hence more democratic, approach to film history.” My experience was to be that audiovisual essays provide a dynamic form for examining and articulating non-linear connections and that their intermedial properties are central to how this enquiry can advance.

This objective from the application helped me to focus my approach and thinking as I reflected on some of the connections between north American film traditions and Brazilian cinema, one of my areas of responsibility within the project, and on a number of the other histories that we were investigating. Among the advantages of a large project team is that different colleagues bring different skills, interests and experience to the task at hand. Readers may recognise, in the quote above, some of the enduring commitments of my colleague, and one of the project’s two Principal Investigators, Lúcia Nagib, who has long argued for understanding world cinema as a polycentric phenomenon. I have an interest in challenging the false opposition of popular and modernist which recurs in film studies and beyond: the films which most inspire me are those that are both popular entertainment and complex and critical works of art at the same time.[9] Examining the creative connections between different artists and practices also appealed, as did finding a videographic way of articulating some of the relationships that were beginning to emerge. By this stage I had already collaborated on two audiovisual essays with colleagues from UFSCAR and the ideas in play seemed particularly suitable for exploring in this form.[10]

The mind map which forms a structuring motif for the essay was the actual page of a notebook on which I began to trace an intriguing network. A mind map charts journeys and relationships that are neither geographical nor chronological, but rather involve other kinds of connections. Here it gave me a way to give form to, and keep track of, a mass of non-linear interrelations. “Carioca” and “Gesture in A Woman Under the Influence” may not have the degree of non-linearity of some web-based forms, or of Chris Marker’s interactive CD-Rom Immemory, for example; the video essay is still a time-based linear medium, unless embedded in a wider matrix. But neither essay closes down the research enquiry with a definitive linear form or conclusion. Rather, while finding forms which seem appropriately contained and complete, they both encourage an awareness of the further networks which branch off from the material presented. A couple of examples departing from “Carioca”: Fred and Ginger can carry us to Brazilian found footage filmmaker Carlos Adriano, whose Sem Titulo #1: Dance of a Leitfossil (2014) combines one of the routines from Swing Time (1936) with fado singer Ana Moura’s “Desfado” as a tribute to his partner, collaborator and renowned film programmer Bernardo Vorobow.[11] The second unit footage in Notorious was shot by Gregg Toland; Toland worked on many films, but none more famous than his collaboration with Orson Welles on Citizen Kane (1941); in 1942 Welles worked in Brazil on the uncompleted film It’s All True, on which he collaborated with Grande Otelo, the two becoming mutual admirers and friends. And so it goes on. This is more than an extended game of six degrees of Kevin Bacon; these movements begin to map some of the complexity of the creative traffic between Brazil and the US, and through different moments in time.

Since the audiovisual essay was completed, more than one person has described it as being “rhizomatic,” and while Deleuze and Guattari hadn’t been part of my thinking there is a link between poststructuralist philosophy and the writing on intermediality which informed the design of the wider project. In the second, enlarged, edition of her book Cinema and Intermediality: The Passion for the In-Between Ágnes Pethő, who was a member of IntermIdia’s advisory board, notes the importance of Deleuze, Foucault and Lyotard to writers exploring “in-betweenness,” one of the three paradigms she identifies in the theoretical field of intermediality, and quotes Bernd Herzogenrath from the introduction to his collection Travels in Intermediality, arguing that “the rhizomatic interconnections among the various media are what constitute the field of intermedia[lity].”[12]

“Carioca” draws on photography, film, theatrical performance, music, voice-over and on-screen captions to explore relationships between film, popular music, histories of dance and cinema exhibition practice, and between different historical periods and national cinemas, and there is a strong connection between the non-linear qualities of the audiovisual essay and its own intermediality. This may be partly because to change medium can easily effect a non-linear shift, but it is also because the kind of enquiry in both this essay and “Gesture” demands an approach which encompasses the relationships between different cultural practices, and that teases out unexpected connections between them. Brazilian cinema is a good test case for an intermedial historiography because of the rich confluences between different artforms, in terms of medium and in terms of the players involved. The connections between art practices are often directly political, but they are also creative in many other ways, embodying innovation and shared dialogue in musical and artistic forms: Caetano Veloso’s decision to open his American songbook album A Foreign Sound (2004) with The Carioca exemplifies a number of these qualities.

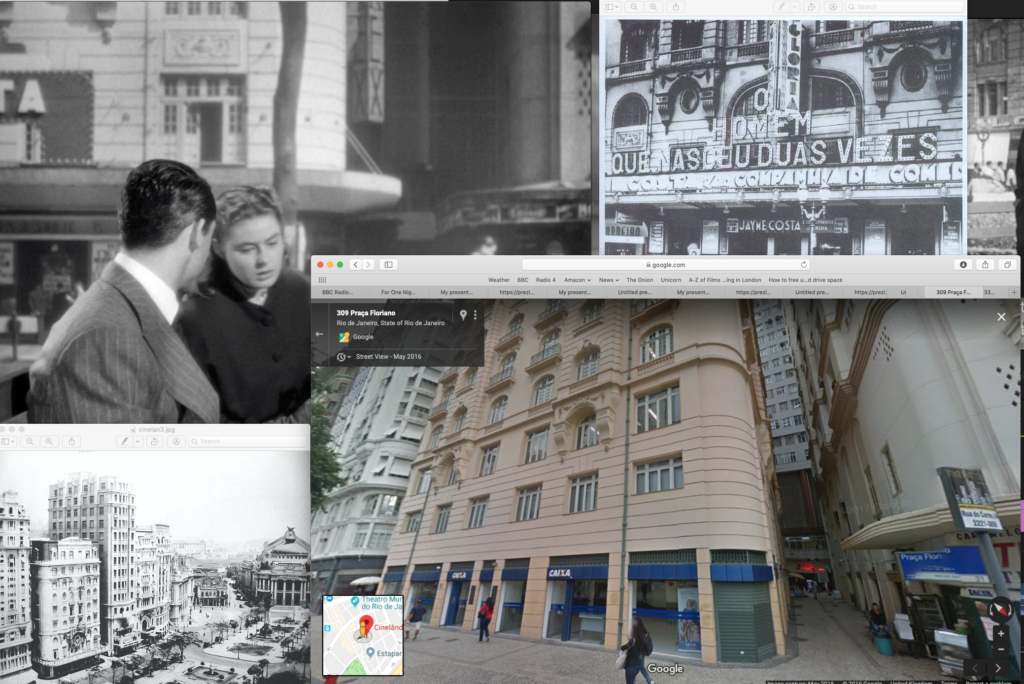

Many mind maps are hierarchical, with a central concept and subsidiary thoughts branching out from it; that is not the case here. (On reflection, it might have been better to describe it as a concept map, after it had been incorporated into the video). In this map, all of the elements have equal weight. Offering a different and more open ended way of presenting knowledge, this map also plays with the colonialist connotations of cartography, at one moment evoking the trope of the aeroplane flying over a map, beloved of Saturday morning adventure serials (and Indiana Jones), a Pan American airways plane (borrowed, in fact, from Notorious [1946]) to introduce Flying down to Rio (1933), literalising the ambitions of a pan-American corporation, and bringing to mind the excessive spectacle of the musical’s conclusion. (Though, as scholars have noted, the expectations and assumptions of the North Americans Flying down to Rio are frequently challenged, including during the Carioca number). The Cinelândia sequence presents an example of an audiovisual essay using media objects to construct or analyse space: the movement between the postcard and Ingrid Bergman’s appearance animates the Praça Floriano Peixoto, and while the aim here is partly to make a point about Notorious’ rear projection, the footage enables the essay to locate two of the three cinemas that staged live action movie prologues in the twenties. (Mapping this out involved drawing on the expertise of Project PI Luciana Correa de Araújo, a historical walking tour led by Rafael de Luna Freire, searching through photographs, and examining the modern facades of the buildings facilitated by Google street view).

Videographic forms, therefore, present different opportunities and methods for implying connections or emphasising oppositions. Editing connects but it can do so in a way that registers difference: when the essay moves from Footlight Parade (1933) to Macunaíma (1969) it does not transition via the mind map but instead through a straight cut—a percussive one, jumping us from Hollywood black and white to tropicalist colour, from orchestrated studio spectacle to parodic fountain in scrubland—which introduces the oppositional qualities of that film’s complex carnivalesque.[13]

Both “Carioca” and “Gesture” reflect on their own processes. A further advantage of the mind map as structuring device is that it allows the research journey of the essay to become part of the audience experience. Later passages of the video reveal some of the chronology of investigation of archival material, particularly the nature of the link between Fanchon and Marco and the Carioca, interrogating Wikipedia’s suggestion that the brother and sister team had created the dance on which the film’s is based. This itself is part of a wider back and forth where, taking something from the rhythms of the number, the audiovisual essay posits different elements only to complicate or answer them: “This reference to Fanchon and Marco’s involvement appears in a number of sources online… ⎸but with suspiciously similar phrasing.” The revelation that there is an image in the Huntingdon archive which depicts an “idea” called the Carrioca [sic], which is unlikely to be picked up by the search tool because of the misspelling, is then countered by the date on the photograph which suggests that it post-dates the film. In an appropriately open-ended way, the process of research is ongoing: I’ve subsequently found advertisements in the Los Angeles Times, from 11th and 12th April 1934, which advertise the appearance at the Paramount Theatre of a Fanchon & Marco presentation including “‘Carioca’ featuring The Original Carioca Dancers of ‘Flying down to Rio’ In Person.”

CONCLUSION

Watching each other’s essays for the first time, and reflecting on them together subsequently, has revealed some striking parallels. Both videos experiment with non-linear methods as opposed to “historiographies drawing on evolutionary chronologies and classical-modern or centre-periphery models,” and both achieve this, at least in part, through embracing intermedial connections. They also deploy a range of audiovisual techniques to make these leaps and connections—layering of dissolved images, split screens, quotation of other works, dialogue and sound. In doing so they uncover the complexity of cultural relationships in their respective areas of enquiry, and suggest new ways of approaching and revealing the intricate histories and the fusion of elements which shape media objects.

In Death 24x a Second, often regarded as a foundational text for videographic film studies, Mulvey discusses how “delayed cinema” can call attention to the “in between-ness” of movements that otherwise vanish into the narrative flow. A “delayed cinema” methodology can occur quite literally, as it does in the beginning of “Gesture in A Woman Under the Influence” where slow motion, freeze-frame and repetition are used to magnify particular gestures within the film. But “Gesture” and “Carioca” extend that methodology into a broader application that engages with film history, enabling an extra-textual magnification of the “in between.” This broader methodology pauses the narrative flow of films and zooms in on particular moments—gestures, sets, props, rear projections, musical numbers—that evoke hidden histories and relationships, opening up spaces “in between” distinct media, artforms and cultures. The audiovisual essay as a form is itself “in between” scholarship and filmmaking, and draws on the potential of digital forms celebrated by Mulvey to frame academic enquiry in novel ways. Our own experiments suggest that the video essay is particularly well suited for non-hierarchical approaches to film history, as it easily accommodates multiple lines of inquiry and offers myriad ways of conveying the complex migrations of images and ideas that underlie many a film text.

Tracy Cox-Stanton is Professor of Cinema Studies at Savannah College of Art and Design. She is the founder and editor of The Cine-Files.

John Gibbs is Professor of Film at the University of Reading. He is one of the editors of Movie: a journal of film criticism and series co-editor of Palgrave Close Readings in Film & Television.

John Gibbs would like to acknowledge a debt to Christian Keathley, in the form of some eloquent observations made in email correspondence, which have helped him to better describe and discuss “Carioca.”

1. Ian Garwood, “The Poetics of the Explanatory Audiovisual Essay,” [in] Transition Journal of Videographic Film and Moving Image Studies 1, no. 3 (2014), http://mediacommons.org/intransition/2014/08/26/how-little-we-know.

2. Christian Keathley, “Journal Editors Speak: Criteria of Evaluation of Video Essays,” Introductory Guide to Video Essays, Learning on Screen: The British Universities and Colleges Film and Video Council, accessed October 10, 2020, https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/guidance/introductory-guide-to-video-essays/finding-coherence-across-journals-guidelines-and-criteria-for-making-curating-and-publishing-video-essays/.

3. Lesley Stern, “Putting on a Show, or the Ghostliness of Gesture,” Lola, Issue 5, November 2014, http://www.lolajournal.com/5/putting_show.html.

4. Georges Didi-Huberman and Alisa Hartz, Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005), xi.

5. Ibid., 3.

6. This problem—how to credit sources within an audiovisual text—is important to confront if we wish to accommodate various digital forms of writing for academic purposes. Last year, I was interested to learn of one scholar’s innovative approach to the problem. University of Iowa graduate student Anna Williams created a podcast for her doctoral dissertation, and she used the sound of a bell to indicate every instance of an endnote (which could be found on an accompanying website) within her script. Anna Williams, “My Gothic dissertation: a podcast” (PhD diss., University of Iowa, Summer 2019), https://www.mygothicdissertation.com/.

7. Eric Faden, “A Manifesto for Critical Media,” Mediascape, spring 2008, https://scalar.usc.edu/works/film-studies-in-motion/media/FADEN%20Manifesto%20for%20Critical%20Media_Spring08.pdf.

8. Viktor Shklovsky and Benjamin Sher, “Art as Device,” in Theory of Prose (Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1990), 1–14.

10. To quote Andrew Britton, “we have only to turn to the classical Hollywood cinema and consider (for instance) Psycho, Written on the Wind, While the City Sleeps, Blonde Venus, Now, Voyager, Bonjour Tristesse, Letter from an Unknown Woman and Gaslight to provide ourselves with the evidence that high modernism could, and once did, exist as a viable popular commercial culture.” Andrew Britton, “The Myth of Postmodernism: The Bourgeois Intelligensia in the Age of Reagan,” Cineaction 12/13 (August 1988): 3–17. Reprinted in Andrew Britton and Barry Keith Grant, Britton on Film (Detroit: Wayne State UP, 2009), 484.

11. Namely, with Suzana Reck Miranda on “Playing at the Margins”, and with Flávia Cesarino Costa on “Chanchadas and Intermediality: On the Musical Numbers of Aviso aos navegantes (Watson Macedo, 1950).”

12. For an article by Adriano on found footage filmmaking, and a critical discussion of Dance of a Leitfossil by Scott MacDonald, see Stefan Solomon, Tropicália and Beyond: dialogues in Brazilian film history (Berlin: Archive Books, 2017).

13. Agnes Pethő, Cinema and Intermediality: The Passion for the In-Between (Second, Enlarged Edition). (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020), 44. Bernd Herzogenrath (ed.) Travels in Intermediality. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2012), 3.

14. One of the great Brazilian modernist strategies is anthropophagy—cannibalism. How do you deal with the imposition of a colonising culture? Swallow it, make use of the bits which are useful to you and discard the rest—certainly a motif and strategy which play out in Macunaíma. Oswald de Andrade’s “Anthropophagic Manifesto” (1928) is the key reference here, which as well as being central to Brazilian modernism of the 1920s was also an inspiration to the artists and musicians of Tropicália. For further discussion, and a reprint of this and other relevant essays, see: Pedro Neves Marques, The Forest and the School / Where to sit at the dinner table? (Berlin: Archive Books, 2014).