Cate Blanchett’s Deconstruction of Performance through Performance

Jennifer O’Meara

Despite widespread acclaim since her break-out performance in Elizabeth (Shekar Kapur, 1998), Cate Blanchett has received little attention within star or performance studies. Charlie Keil’s comparative essay on Blanchett and Kate Winslet is an exception, providing a useful overview of her as an actress who ‘‘staked out a claim to stardom predicated explicitly on acting talent over celebrity.’’[1] This article builds on Keil’s insights by focusing on a sub-set of performances that reveal Blanchett’s talent for embodying roles that deconstruct the performance process. I argue that, despite media profiles that stress how she ‘‘disappears’’ into roles,[2] the actress is particularly drawn to reflexive parts that make a dramatic feature of characters’ own performances. In a discussion of ‘‘performing performing,’’ Charles Affron explains that when an actor performs a role within a role, ‘‘we become conscious of a high level of fictivity.’’[3] Although Affron was concerned with overtly reflexive performances involving the mise-en-abyme of a play or film within the film, I focus instead on three roles that require Blanchett to perform characters whose own performances are failing, and who are ‘‘split’’ in different ways.

In Coffee and Cigarettes (Jim Jarmusch, 2003) Blanchett plays two characters (a fictionalized version of herself and her cousin), with the performances combined by a split screen. This duality offers rich insights into screen acting and provides a unique opportunity to see an actress do an impersonation, of her own impersonation, of herself. Next, in I’m Not There (Todd Haynes, 2007) Blanchett plays one persona of a character (Bob Dylan) who is split across six performers. Finally, in Blue Jasmine (Woody Allen, 2013) Blanchett performs a character whose traumatic past and subsequent breakdown require her to convey a mental split through external signs. I demonstrate how, through layered nuances of voice and body, Blanchett creates the impression that the character is also performing. To do so, I draw on James Naremore’s discussion of acting that requires a breakdown in expressive coherence.[4] Initially detailed by social psychologist Erving Goffman in regard to the dramaturgy of everyday life,[5] Naremore has discussed cinema’s potential to reveal fissures in a performance: ‘‘Ordinary living usually requires us to maintain expressive coherence, assuring others of our sincerity; theater and movies work according to a more complex principle, frequently demanding that actors dramatize situations in which the expressive coherence of a character either breaks down or is revealed as a mere ‘act.’’’[6]

Finally, I suggest Blanchett’s strong performances reflect her personal contributions and strong collaboration with directors .[7] I explore how Sharon Carnicke’s discussion of the actor as auteur helps illuminate Blanchett’s performances in the selected films.[8] More generally, I take Carnicke’s approach that ‘‘[e]xamining the physical and vocal choices that appear on screen as both interpretative and constitutive of style offers a more useful means by which to analyze performance than those based primarily on actor training.’’[9] I therefore consider what appears in the finished product rather than alignment with any given school of acting to support my argument that Blanchett’s reflexive performances provide viewer and actress alike with the opportunity to deconstruct the performance process.

Playing Herself and Playing Opposite Herself

Media reception of Blanchett is overwhelmingly positive, with frequent references to her ‘‘alert intelligence’’[10] and desire to be challenged.[11] Such comments appear justified; highly articulate in interviews, Blanchett frequently discusses acting in abstract rather than descriptive terms and has shown a keen interest in academic coverage of Australia’s cultural policy.[12] Her appointment as artistic co-director (with husband Andrew Upton) of the Sydney Theatre Company from 2008 to 2012 further strengthened her reputation as a ‘‘serious’’ actress with ambitions to direct and coordinate, as well as perform in, productions. Although beginning in period films, Blanchett proved her versatility in major and minor roles in productions such as Charlotte Gray (Gillian Armstrong, 2001), The Aviator (Martin Scorsese, 2004), and Little Fish (Rowan Woods, 2005). She subsequently reprised her role as monarch in Elizabeth: The Golden Age (Shekhar Kapur, 2007). Discussing her performance in Elizabeth: The Golden Age, Keil notes the presence of heightened theatricality, but argues that the film accounts for the histrionics by suggesting ‘‘the monarchy involves displays of self-conscious performance.’’[13] But as I will demonstrate, rather than being an exceptional case, heightened displays of self-consciousness are a recurring feature of Blanchett’s work.

In ‘‘Cousins,’’ one segment of Coffee and Cigarettes (2003), Blanchett plays herself, Cate, and Shelly, a fictional cousin. In the analysis to follow, all references to ‘‘Cate’’ refer to the character in Coffee and Cigarettes, while references to the actress are made through her last name. She filmed a character a day, with the two subsequently combined by split screen. Jim Jarmusch was inspired by Blanchett’s wide variety of roles and the unusual set-up provides Blanchett and viewer alike with an opportunity to deconstruct aspects of the performance process. While literature on film acting notes the difficulty of distinguishing moments of the actor’s intentionality from those of the director, and from the actor simply ‘‘being,’’ the unique circumstances of Coffee and Cigarettes make it easier to see Blanchett’s choices as an actress. One moment that clearly illustrates Blanchett’s agency occurs when Shelly mimics one of Cate’s earlier hand movements (when she tightly laces her fingers together), while mocking Cate further with an exaggerated version of her facial expression. In this and various other scenes, it appears that Blanchett has set up a moment on the first day of shooting (as Cate), that she responds to on the second (as Shelly).

Blanchett’s performances in the film also provide a good opportunity to do a more in-depth vocal analysis, the kind Carnicke encourages as a useful means by which to analyze performance. Though the two roles are differentiated physically with changes in posture, hair and make-up, the vocal nuances strongly suggest Blanchett’s careful planning; while Shelly’s resentment of Cate’s fame and lifestyle is clear from the script, Blanchett develops this further by isolating words associated with celebrity and delivering them, as Shelly, in a mocking tone. When she pronounces the words ‘‘movie star’’ with a false sense of grandness, she simultaneously labels Cate as one and ridicules the idea that she should be considered one. Referring to Cate’s interviews with the press, Shelly over-enunciates the word ‘‘junket,’’ capturing her contempt for them through a harsh and extended second syllable. Also, Shelly’s more pronounced Australian accent suggests an acknowledgement on Blanchett’s part that she has suppressed aspects of her background for stardom. Indeed, as Keil notes, in adopting accents including Russian and Irish, Blanchett has broadened her range of accents ‘‘to the point where the skill is an obvious part of her performance repertoire.’’[14] The more low-key character of Cate also has vocal tics that reveal a mild annoyance with Shelly that is never explicitly verbalized. For example, Cate responds to several comments with sighs of resignation that become louder over time. Blanchett also breaks up the line, ‘‘And I just thought it would be nicer if we met down here’’ with a cough after the word ‘‘nicer.’’ Since Shelly’s smoke is the reason she coughs, the specific placement adds irony and reveals Blanchett’s forethought with regard to the finished product.

But to address the issue of authorial intent were these subtleties of voice initiated by Blanchett or requested by Jarmusch? Consultation with a selection of interviews suggests a combination of both, since each has stressed the importance of the voice as a performance tool. The voice is such a priority for Jarmusch that he will not allow his films to be dubbed for overseas markets. As his agent Bart Walker explains, he insists that ‘‘[t]he integrity of his film changes when the actor’s voice is changed.’’[15] Blanchett, on the other hand, has discussed the ‘‘complicated neurolinguistic process’’ involved in delivering lines so that the words do not come across as pre-written.[16] Actor and director are therefore well-aligned, with Blanchett paying her vocal performance the kind of close attention Jarmusch values.

The character of Cate is initially more sympathetic since Blanchett plays herself as pleasant and polite, despite her cousin’s inappropriate behavior and denigrating remarks. However, in another example of reflexivity, she also suggests awareness of the importance of her public persona. In a telling moment in which Shelly reveals the special treatment she received when someone mistook her for Cate, her face changes to a look of concern which, in light of Shelly’s general behaviour, can be read as concern that she damaged her reputation. Taken as a whole, although less than ten minutes long, the segment is exceptionally rich in terms of deconstructing the performance process. As Keil explains, the short is loaded with subtext, including the idea that celebrities risk seeing everything, and everyone, as extensions of themselves.[17] Although, in the film, Cate seems concerned with carefully managing her persona, Blanchett’s willingness to take experimental roles suggests otherwise. This is particularly the case with I’m Not There, in which she is the only actress to join five actors playing Bob Dylan.

Androgynous Acting in I’m Not There

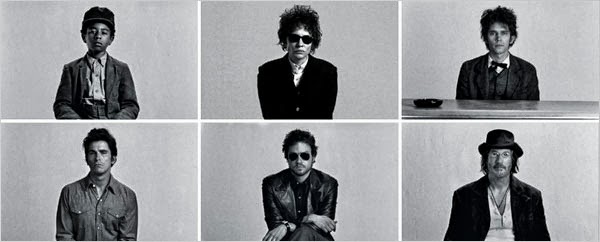

Released four years after Jarmusch’s film, as another experimental treatment of celebrity, I’m Not There is an interesting complement to Coffee and Cigarettes. Rather than producing the standard chronological biopic, writer-director Todd Haynes captures the sense of Dylan’s larger than life persona by separating aspects of it among six performers of various age, nationality, race and gender. Blanchett plays the Dylan referred to as Jude Quinn, who renounced folk to public dismay in the period between 1965-1966. From an early stage, Haynes intended for Jude to be played by a woman as he was keen to capture the ‘‘feline quality’’ of Dylan in this period.[18] But while it has become the norm for actresses to prove dedication to the craft with roles that require a compromise of their glamorous looks, few have embraced androgyny by crossing the gender divide. According to Haynes, Blanchett researched the part extensively by watching documentaries on Dylan and studying press conferences from his 1966 tour.[19] Again, attention can be drawn to her vocal performance; not only did the role require Blanchett to employ an accent, but to capture elements of a distinctive male voice. Dylan’s idiosyncratic phrasing is channelled with, as Patrick Barkham notes in an interview for The Guardian, the use of elongated vowels and seemingly random emphases.[20] Further comparisons can be drawn between the deconstruction of performance in Haynes’s and Jarmusch’s films. Just as Blanchett parodies her public image in Coffee and Cigarettes, Jude parodies his when shouting ‘‘Do your early stuff, man’’ at a statue of Jesus.

Furthermore, David Yaffe sums up his response to Blanchett as Dylan as both believing in her interpretation and simultaneously ‘‘appreciating its audacity.’’[21] The same could be said of Coffee and Cigarettes and, as will be demonstrated below, Blue Jasmine. While not low key, these performances are contrived with a subtlety similar to the kind of everyday performances Goffman details in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. For Goffman, ‘‘A performer who is disciplined, dramaturgically speaking, is someone who remembers his part and does not commit unmeant gestures or faux pas in performing it.’’[22] Although everyday performances are often incoherent, the incompatible ‘put on’ elements of social acting are difficult to determine and require careful monitoring of the performer. [23] Unlike in reality, however, actors and film-makers can carefully design the visual and verbal signs for understanding the performer and his/her inconsistencies. Significantly, this requires the kind of ‘‘performing performing’’ and ‘‘performance within performance’’ that was noted, respectively, by Affron and Naremore, and which depends on the idea of a gap between the ‘‘true’’ and performed self.

But precisely how does this relate to Blanchett and the roles under discussion? The gap between a character’s ‘‘true’’ and performed self is carefully revealed in Coffee and Cigarettes since Shelly reveals a constructed identity (she is exposed as less confident and happy) in the closing moments; when Cate leaves to do press interviews, Shelly enthusiastically reciprocates, saying ‘‘send my love to everyone your end,’’ but, after a six second pause that allows Cate to move further away, adds, ‘‘if they even remember me.’’ The enthusiasm in her face and voice are gone to reveal a sense of hurt. Cate shouts back in voice-off, ‘‘Hey, maybe next time I’ll get to meet Lou!’’ and Shelly smiles again as she answers ‘‘Yeah!’’ but then mutters under her breath, ‘‘It’s Lee.” The sequence neatly captures that although Cate is the actress by occupation, Shelly has also been performing. Its overt reflexivity also alludes to the complex relationship between professional and everyday actors that Naremore describes: ‘‘professional acting could be regarded as part of an unending process—a copy of everyday performances that are themselves copies.’’[24] As Shelly, Blanchett mimics the character of Cate, who is equally removed from the off-screen Blanchett who, in keeping with Goffman’s socio-psychological model, presumably employs a degree of performance in everyday life. In these ways, Shelly, Cate and Blanchett are located at various points in Naremore’s unending performance process.

Questioning of a character’s fundamental self is equally found in I’m Not There. Critical reception of the film praised Blanchett’s performance, with several reviewers rating her embodiment of Dylan as the most convincing. The experimental casting therefore recalls the notion of gender as performance, since, despite being female, Blanchett credibly portrays the male musician. Furthermore, as critic Peter Bradshaw explains, the film’s depiction of Dylan’s parallel persona ‘‘repudiates the typical biopic assumption that the essential truth about someone can be told in a linear couple of hours.’’[25] Like Blanchett’s simultaneous roles in Coffee and Cigarettes, the part of Jude/Dylan questions the assumption that any character, or indeed person, has a single, fixed self. Discussing Dylan, Blanchett also stresses this ambiguity when she reflects that ‘‘the truth isn’t a static thing.’’[26] Again, such an acknowledgement is evident in her attraction to roles in which the character displays a divided self.

Blue Jasmine and Blue Jeanette

This dimension of performance is explored most thoroughly in Blue Jasmine, in which Blanchett plays the title role of a woman whose anxiety has her dependent on alcohol and prescription drugs. As Naremore notes, characters who are alcoholics or addicts provide ample ground for showcasing expressive incoherence and Woody Allen’s creation is no exception.[27] Flashbacks are used to show Jasmine’s attempts to cope with her husband Hal’s (Alec Baldwin) imprisonment for fraud and subsequent suicide, as well as the loss of her home and her son (who disowns her out of anger). Jasmine’s behavior aligns with elements of a post-traumatic stress disorder; she frequently tunes out her immediate environment when reliving stressful events, with disassociation from the present marked by her trance-like speech throughout. However, Jasmine’s complex sense of self appears to pre-date the dramatic events with Hal, since, as her sister Ginger (Sally Hawkins) reveals, Jasmine’s real name is Jeanette. The adopted moniker is an early signal of the character’s image management and class-climbing aspirations, with various scenes constructed to increase the audience’s awareness of Jasmine’s control of her image.

Romantically, she plays hard to get in a complex fashion. When Dwight (Peter Sarsgaard), the object of her affection, calls, Jasmine pretends to be busy despite frantically waiting to hear from him. The extent of her contrivance is revealed when she asks him to hold and counts to ten before speaking again. Dwight eventually discovers Jasmine’s hidden history and she arrives home to Ginger, upset. Yet despite Jasmine’s wet and dishevelled appearance, she fixes her hair as she walks to the bathroom, repeating a gesture Blanchett performs in earlier scenes when Jasmine is calm and well groomed. By repeating this gesture in a scene in which Jasmine’s physical appearance matches her inner turmoil, Blanchett conveys the character’s inability to let go of the ‘‘together’’ persona she has adopted for so long. Other ways in which Blanchett conveys Jasmine’s falseness include her careful pronunciation of designer labels, and the way her mouth is kept rigid as though the muscles are frozen in place. Blanchett adds a stutter to Jasmine’s collection of anxious tics, particularly when she speaks of Hal (H-H-Hal), her deceased husband. Blanchett’s mannerisms therefore seem carefully designed to convey Jasmine’s struggle to maintain control and the appearance of normalcy.[28]

Again, Blanchett’s comments on the role suggest an intuitive understanding of the reflexivity required of the performance. When interviewed for the film’s production notes, she makes frequent reference to Jasmine’s performed self and denial of truth. She identifies the character’s theatrical decision to change her name, explaining that ‘‘she always steps slightly sideways from the truth.’’[29] Blanchett also echoes Goffman’s discussion of the theatrical roles individuals choose for themselves, identifying the social component of Jasmine’s constructed self: ‘‘She is very conscious of how she’s perceived and her desire to control that perception, the outward shell of who she is, trumps the discovery of who she actually is.’’[30] As the above examples suggest, Blanchett repeats gestures suited to earlier scenes in later ones, in which the gestures jar, in order to convey a gap between Jasmine’s outward shell and the reality she tries to hide. Jasmine’s duplicity is also communicated directly by the dialogue, when she makes inconsistent points regarding her past and current life. At times, only the audience is aware of the full picture and they must determine which version of events is more likely to be true based on Blanchett’s tone of voice and expressions. As an actress, her task is therefore to help the audience realize that they cannot take Jasmine at face value, and why not. In part because Jasmine’s half-truths involve self-deception, as opposed to strategic lying, Blanchett succeeds in doing this in a way that garners the character sympathy.

Blanchett as a Collaboratory Actor

Yet it would be misleading to suggest Blanchett’s attachment to these roles is based solely on the reflexivity of the characters; she also takes the director into account when selecting projects. As Keil notes, despite her prolificacy, Blanchett’s work with well-respected directors like Sally Potter, Martin Scorsese and Tom Tykwer suggests she is discerning when choosing filmmakers with whom to work.[31] I will now consider Blanchett’s agency in the chosen roles, a subjective task given that performance studies inherently involve ambiguity when determining which elements of the final product originated with the actor. Editing and sound recording techniques can radically alter the actor’s performance, as Carnicke explains when describing montage’s power to ‘‘redefine the relationship between director and actor from one of collaboration to one of authority and control.’’[32] Using the director as auteur approach risks taking credit away from the actor, so Carnicke loosely categorises directors into 1) those who view actors as collaborators and 2) those who consider actors ‘‘primarily as props to manipulate within the mise-en-scene.’’[33] Carnicke attempts the difficult task of measuring actors’ responses to different directors. Comparing Jack Nicholson’s use of voice and body in The Passenger (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1975) and The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980), she concludes that he is highly flexible in his ability to adapt to differing direction styles.

The same could be said of Blanchett. When asked her view on different working relationships with directors, she displays a keen awareness of the open-mindedness required: ‘‘Some directors want to know what they’re going to receive before they receive it. And I don’t mind that; I just treat it as part of the rehearsal process. It really depends on that material…. In the final analysis, it’s the communal conversation that’s important.’’[34] With Blue Jasmine, Blanchett takes cues for her performance from the script itself. Allen is known for his minimal direction and she describes how she had to ‘‘deprogram’’ herself from expecting him to suggest things.[35] Instead, she appears to take inspiration from details of the writing. For instance, Ginger comments that Jasmine has a habit of looking the other way when she doesn’t want to see something and, in turn, Blanchett frequently stares into space and, as evidenced by the film’s use of flashback, into her past.

However, in terms of Blanchett’s freedom to author her own performance, the selection of roles is also important. Although it is generally difficult to distinguish moments of the actor’s intentionality from those of the director, or from the actor simply ‘‘being,’’ such choices become more obvious when Blanchett plays opposite herself (as in Coffee and Cigarettes), or when she shares one character with other actors (as in I’m Not There). For the latter, Blanchett compiled details for the role from actual recordings of Dylan. Although it is difficult to determine how directive Haynes was on set, she took it upon herself to locate and perfect usable mannerisms from existing sources. In a feature for Interview Magazine,Jarmusch also suggests Blanchett was the controlling force behind both portrayals in Coffee and Cigarettes. Delivering the performances to someone invisible, he commends her ability to keep ‘‘the nuances of each character’s reactions in [her] head.’’[36] Jarmusch notes that Blanchett developed the character differences ahead of time and, while admitting to getting lost himself, remained confident that she was keeping track. In this case, then, Blanchett seemed to have considerable control over both performances. Alternatively, although Jarmusch praises Blanchett’s character construction, it was his experimental premise that provided her with the opportunity to create complex vocal dynamics between the ‘‘neurolinguistic process’’ of two characters. It therefore seems fair to consider their collaboration as a mutually beneficial one that allowed Blanchett considerable creative autonomy.

The aim of this article was to demonstrate how Blanchett’s role choices and acting style push at the boundaries of conventional screen performance. In order to consider reflexivity as a recurring feature of her roles and performance style, I focused on three of her more experimental performances. By playing herself, and opposite herself, in Coffee and Cigarettes, Blanchett helps viewers gain a better understanding of how performance is made up of distinct choices of gesture and physical and vocal expression. The viewer is also afforded a rare chance to see an actress do an impersonation of her own impersonation of herself. In I’m Not There, by playing one aspect of a famous musician of the opposite sex, Blanchett draws our attention to the difficulty of capturing the true nature of a given person, as well as cinema’s potential to complicate this further through casting that questions gender as biologically determined. Issues of multiple selves and constructed identities are also to the fore with Blue Jasmine. As my analysis suggests, the role required Blanchett to distinguish between the inner turmoil and difficult past of Jeanette and the more ‘‘together’’ and ambitious Jasmine.

Geoffrey Rush, who acted alongside Blanchett in Elizabeth and Elizabeth: The Golden Age also identifies her willingness to highlight rather than downplay ambiguity regarding character. He explains how she extracts from the material ‘‘all the many dark, mysterious, and conflicting elements of the character that are going to make it engaging and thrilling for the audience.’’[37] As I have shown, part of Blanchett’s ability to engage and thrill us would seem to come from her willingness to construct her own performance so that the characters’ performances are simultaneously revealed. Relating her role as actor to the eventual experience of the viewer, she explains how ‘‘[t]he same questions an audience asks are the ones I ask as an actor. The difference between me and an audience member is that, as an actor, you absolutely don’t want to solve or answer or define those things. You just want to keep all those questions alive.’’[38] Choosing roles that are deliberately ambiguous about the ‘‘true’’ versus performed nature of a character is one way to help keep the audience’s questions alive.

Because such roles provide the opportunity to showcase performance skills, their appeal to Blanchett is understandable. As Naremore explains, parts of this nature require the actor to demonstrate virtuosity ‘‘by sending out dual signs.’’[39] In Coffee and Cigarettes and Blue Jasmine, she creates multi-layered performances through nuanced vocal deliveries and repeated gestures. Close analysis of Blanchett’s aural delivery reveals how, as a barometer of emotion, her voice strengthens or undermines the words as written.[40] By changing the intensity, pitch and speed, Blanchett creates the impression that some of her characters’ words are more genuine than others. In I’m Not There, the layering of performance largely comes from the narrative structuring with six performers acting out various elements of one role. The layering is also built into the structure of Coffee and Cigarettes since Blanchett plays its only two characters. In various ways, then, the three films under discussion reveal Blanchett’s attraction to roles that question the idea of a character’s ‘‘true’’ self, allowing her to deconstruct elements of performance in the process.

Jennifer O’Meara is a PhD candidate in Film Studies at Trinity College Dublin, where her research focuses on dialogue in independent cinema. Her articles have appeared, or are forthcoming, in Cinema Journal, The Soundtrack, and The Films of Wes Anderson: Critical Essays on an Indiewood Icon (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

[1] Charlie Keil, “Kate Winslet and Cate Blanchett: The Performance is the Star” in Shining in Shadows: Movie Stars of the 2000s, ed. Murray Pomerance (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2011) 182. Keil makes this remark in respect of both Blanchett and Kate Winslet.

[2] John Lahr, ‘‘Disappearing Act’’ in New Yorker, February 12, 2007, 38. Accessed on 1/29/14 at http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/02/12/070212fa_fact_lahr

[3] Charles Affron,‘‘Performing Performing: Irony and Affect,’’ Cinema Journal 20, no. 1 (Fall 1980), 42.

[4] James Naremore, ‘‘Expressive Coherence and Performance within Performance’’ in Acting in the Cinema, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990) 68-82.

[5] Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Harmondsworth: Penguin, [1959] 1990).

[6] Naremore, ‘‘Expressive Coherence,’’ 70.

[7] Blanchett comments on this directly when she notes that ‘‘[f]ortunately, for the most part I’ve worked with directors who trust actors.’’ Richard Porton, ‘‘Trusting the Text: An Interview with Cate Blanchett’,” Cineaste Vol. 32, Issue 2 (Spring 2007), 18.

[8] Sharon Marie Carnicke, ‘‘Screen Performances and Directors’ Visions’’ in More Than a Method: Trends and Traditions in Contemporary Film Performance, ed. Cynthia Baron, Diane Carson, and Frank P. Tomasulo (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004) 42-52.

[9] Carnicke, ‘‘Screen Performances,’’ 47.

[10] Richard Corliss, ‘‘The 2007 TIME 100: Cate Blanchett,’’ TIME, May 03, 2007. Celeste Simons refers to Blanchett as ‘‘intelligent, entrepreneurial and not content to coast along on her beauty and talent.’’ Celeste Simons, ‘‘Stars and star vehicles: Giorgio Armani, Cate Blanchett, Liv Ullmann, Henrik Ibsen and the Norwegian-Australian connection,’’ Nordic Notes, Vol. 12 (2008) 5.

[11] As Jenny Comita summed up in a profile of the actress, ‘‘If [a role] doesn’t sound a little impossible, Cate Blanchett is not interested.’’ Jenny Comita, ‘‘Queen Cate’’, W Magazine, October 2007, accessed on 1/29/14 at http://www.wmagazine.com/film-and-tv/2007/10/blanchett_cate/. Charlie Keil similarly argues that Blanchett’s choice of roles is guided by a ‘pursuit of acting challenges’; ‘‘Kate Winslet and Cate Blanchett,’’183.

[12] In 2006, Blanchett lauded a paper by cultural economist David Throsby entitled ‘‘Does Australia Need a Cultural Policy?’’ in order to raise awareness. Ben Cubby, ‘‘Cate’s wish: a culture that touches all,’’ Sydney Morning Herald, February 9, 2006. Accessed on 1/28/14 at http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/cates-wish-a-culture-that-touches-all/2006/02/08/1139379573550.html

[13] Keil, ‘‘Kate Winslet and Cate Blanchett,’’ 198.

[14] Keil, ‘‘Kate Winslet and Cate Blanchett,’’ 188.

[15] Lynn Hirschberg, ‘‘The Last of the Indies,’’ New York Times, July 31, 2005, accessed on 1/29/14 at http://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/31/magazine/31JARMUSCH.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

[16] Porton, ‘‘Trusting the Text,’’ 19. Blanchett makes this comment in a press interview for Notes on a Scandal, yet it appears to reflect her more general approach to the voice.

[17] Keil, ‘‘Kate Winslet and Cate Blanchett,’’ 190.

[18] David Yaffe, Bob Dylan: Like a Complete Unknown (New Haven, Conn., Yale University Press, 2011) 47.

[19] Peter Bradshaw, ‘‘I’m Not There,’’ The Guardian, 21 December 2007. Accessed on 1/28/14 at http://www.theguardian.com/film/2007/dec/21/drama

[20] Patrick Barkham, “The power and the glory,” The Guardian, October 26, 2007. Accessed on 1/28/14 at http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2007/oct/26/awardsandprizes

[21] Yaffe, Bob Dylan, 47.

[22] Goffman, Presentation of Self, 210.

[23] Goffman, Presentation of Self, 143.

[24] Naremore, ‘‘Expressive Coherence,’’ 70.

[25] Bradshaw, “I’m Not There.” n.p.

[26] Barkham, ‘Power and the Glory’, n.p.

[27] Naremore, ‘‘Expressive Coherence,’’ 76.

[28] Difficulties in performing stuttering have been highlighted by Donna Peberdy in her study of James Earl Jones. Jones is generally required to control his natural stutter for roles and Peberdy explains how, unlike a lisp, a stutter is a speech affectation that can be hidden and controlled through a variety of techniques. In the case of Jasmine, it is therefore fitting that she would stutter when referring to her dead husband, revealing a relationship between her inability to control her feelings and an inability to control her stutter. Peberdy, ‘Male Sounds and Speech Affectations: Voicing Masculinity’ in Film Dialogue, ed. Jeff Jaeckle (New York; Chichester: Wallflower, 2013) 206-219

[29] Sony Picture Classics. Blue Jasmine Press Kit, 5. Accessed 1/27/14 at http://www.sonyclassics.com/bluejasmine/bluejasmine_presskit.pdf Blue Jasmine Press Kit, 5.

[30]Blue Jasmine Press Kit, 6.

[31] Keil, ‘‘Kate Winslet and Cate Blanchett,’’ 189.

[32] Sharon Marie Carnicke, “Lee Strasberg’s Paradox of the Actor” in Screen Acting, ed. Alan Lovell and Peter Krämer (London: Routledge, 1999) 76

[33] Carnicke, ‘‘Screen Performances,’’ 45.

[34] Porton, ‘‘Trusting the Text,’’ 18.

[35]Blue Jasmine Press Kit, 10.

[36] Cate Blanchett, ‘‘Jim Jarmusch by Cate Blanchett,’’ Interview Magazine 34.5 (June 2004) 49.

[37] Adam Green, ‘‘Cate Blanchett: Truth or Dare,’’ Vogue.com,December 2009. Accessed on 1/27/14 at http://www.vogue.com/magazine/article/cate-blanchett-truth-or-dare/#1

[38] Porton, ‘‘Trusting the Text,’’ 17.

[39] Naremore, ‘‘Expressive Coherence,’’ 76.

[40] This is in keeping with David Sonnenschein’s discussion of the voice as an instrument that carries two meanings: one verbal, the other, intonational and reflects the speaker’s feelings in Sound Design: The Expressive Power of Music, Voice and Sound Effects in Cinema (Studio City, Calif. Michael Wiese Productions) 138-9.