Chris Marker and the Essay Film: a Presentation by Timothy Corrigan

by Tracy Cox-Stanton

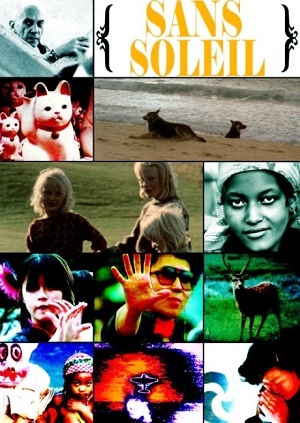

As part of the Savannah Film Festival, the Department of Cinema Studies screened Chris Marker’s 1982 documentary Sans Soleil, and offered a lecture presentation by visiting scholar Timothy Corrigan. Corrigan’s recent book The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker, winner of the 2012 Katherine Singer Kovács Award for the best book in film and media studies, illuminates a cinematic tradition that has remained largely invisible to film scholars and historians. Analogous to the literary essay (beginning with Michel de Montaigne in the 16th Century), the essay film represents a “thinking out loud,” as it experiments with a shifting subjectivity that encounters various public experiences. The destabilizing effect of that interaction between an individual subject and the public sphere is key to Corrigan’s definition of the essay film, and it forms the basis of the many examples thoughtfully analyzed in his book.

As part of the Savannah Film Festival, the Department of Cinema Studies screened Chris Marker’s 1982 documentary Sans Soleil, and offered a lecture presentation by visiting scholar Timothy Corrigan. Corrigan’s recent book The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker, winner of the 2012 Katherine Singer Kovács Award for the best book in film and media studies, illuminates a cinematic tradition that has remained largely invisible to film scholars and historians. Analogous to the literary essay (beginning with Michel de Montaigne in the 16th Century), the essay film represents a “thinking out loud,” as it experiments with a shifting subjectivity that encounters various public experiences. The destabilizing effect of that interaction between an individual subject and the public sphere is key to Corrigan’s definition of the essay film, and it forms the basis of the many examples thoughtfully analyzed in his book.

Corrigan suggests that though its lineage can be traced to the first historical avant-garde as well as the silent documentary tradition, the essay film really begins only after 1945. The post-World War II transformations that enabled the French “new wave” in narrative filmmaking likewise affected nonfiction filmmaking. In Alain Resnais’s documentary about Nazi concentration camps, Night and Fog (1955), for example, the authoritative, “voice of God” narrator that distinguished earlier documentaries is eschewed in favor of the questioning, poetic, and embodied voice-over of Jean Cayrol, a camp survivor. This film is “an early and widely recognized example of the essay film,” Corrigan writes, because it so powerfully frames the complex encounter of an individual subject (Jean Cayrol) with a horrific public sphere (the concentration camps), resulting in the subject’s necessity to rethink itself and its relationship to that public sphere. “The crisis of World War II, the Holocaust, the trauma that traveled from Hiroshima around the world, and the impending cold war inform, in short, a social, existential, and representational crisis that would galvanize an essayistic imperative to question and debate not only a new world but also the very terms by which we subjectively inhabit, publicly stage, and experientially think that world.”[1] It is not coincidental, then, that many essay films confront historical traumas, or rather, the relationship of the individual to historical trauma.

Although this cinematic tradition spans across the late-20th and 21st centuries, Corrigan centered his remarks at the Savannah Film Festival around Chris Marker’s rich and perplexing film Sans Soleil, or Sunless (1982). “If Marker’s Sunless (1982) represents one of the widely acknowledged triumphs of the [essay film] practice, it represents the triumph of an amalgamation and orchestration of modular layers, as a travelogue, a diary, a news report, and a critical evaluation of film representation.”[2] Indeed, the film’s many layers can alienate confused viewers who search in vain for narrative coherence, or worse, a thesis statement.

Corrigan’s audience of SCAD faculty and students, who had recently attended a screening of Sunless, represented a wide range of respondents. Among those students who encountered the film for the first time, comments varied from “I’m not sure what I was supposed to get from the film,” to “I loved the gentleness of the film’s approach, as it moved from continent to continent, topic to topic.” The ensuing discussion captured the heart of what’s at stake in the essay film and reinforced Corrigan’s insistence that labels such as “reflexive documentary” or “subjective documentary” don’t adequately differentiate this mode of filmmaking. Not entirely in jest, Corrigan answered that Sunless is about “things that quicken the heart,” an allusion to the film’s mention of 11th Century Japanese writer Sei Sonagon’s habit of making lists, most famously a list of “things that quicken the heart.” That phrase, perhaps more than any other in the film, might help us trace the associative links between the film’s reflections on Japanese popular culture, the atomic bomb, civil war in Guinea Bisseau, animism, and an Icelandic volcano.

Sunless’s ambitions surpass, and even question, the relevance of an “about,” a cohesive narrative or a thesis statement. Rather, the film aims to gently, if unflinchingly, ponder the varieties of human responses to life’s mysteries and its unthinkable traumas, noting how we ritualize, individually and as a culture, the loss of a cat, the anarchic joy of rock and roll, or the destruction of an entire population by an atomic bomb. As Corrigan notes, throughout Marker’s long and diverse film and media career, “his concerns have remained remarkably consistent: memory, loss, history, human community, and how our fragile subjectivity can acknowledge, represent, surrender, and survive these experiences.”[3] The vehicles of narrative cinema, avant-garde practice, or even subjective documentary aren’t quite adequate for conveying the associative possibilities and intellectual provocations that fantastically meld in Marker’s aesthetic. As Corrigan theorizes it, the essay film offers us a rubric to better understand Marker’s aims and to help us as spectators to position ourselves in relation to the film, whose style and purpose exists, as Corrigan writes, “well outside the borders of conventional pleasure principles.”[4] Corrigan’s address, like Marker’s films, offered festival attendees a wonderful opportunity to expand beyond the festival’s more conventional and contemporary fare and to engage an important moment of film history, one that continues to resonate through film culture.

Published December 3, 2012.

Notes

[1] Timothy Corrigan, The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 63.

[2] Ibid., 8.

[3] Ibid., 36.

[4] Ibid., 5.

Tracy Cox-Stanton is Professor of Cinema Studies at Savannah College of Art and Design, and the creator and editor of The Cine-Files.