Animalistic Laughter: Camping Anthropomorphism in Roar

Sean Donovan

In 1971, Tippi Hedren participated in a photoshoot with Life magazine photographer Michael Rougier, showcasing her husband Noel Marshall and their family lounging in their spacious Sherman Oaks home. Far from a typical look at the rich and famous, these photos commanded attention through the presence of Neil, a 400-pound lion that is featured with the family in a variety of quotidian tableaux: with Hedren by the pool (see FIGURE 1), with Marshall in his office, even with Hedren’s daughter Melanie Griffith in her bed.[1] These photographs were an expression of the family’s devout lion-love, willfully selling the fantasy of the Hedren-Marshall family living alongside an adult lion in a utopian union of animal and man (Neil actually lived in an animal preserve called Soledad Canyon, which Marshall purchased shortly after the photoshoot). As revealed in Hedren’s 2016 memoir Tippi, the photos also bore a calculated purpose: they were part of an effort to spur buzz in Hollywood about Roar (1981), Hedren and Marshall’s dream project, a family adventure film celebrating the majestic beauty of lions. Marshall would direct and star alongside Hedren, who was giving up birds for a new and even more ferocious animal co-star. Completed almost ten years after this glamorous photoshoot, Roar had a production history that completely contradicted the glossy leisure myth promoted by Rougier’s photography. Writing about the photoshoot years later, Hedren remarked, “I didn’t learn until many years later how naive and stupid we were.”[2]

FIGURE 1. Tippi Hedren and Neil the lion (Michael Rougier, Life, 1971)

Roar in production suffered from an idealistic reverence for lions that bore deadly results. Ostensibly, the filmtells the story of a distracted lion researcher (played by Marshall) whose family comes to visit his ranch in an unnamed part of Africa (some exteriors were shot in Kenya) to find themselves alone with the lions, and entirely unprepared for how to care for the mighty beasts.[3] Even though the plan for the film was always to show lions as capable of causing great harm to humans if not treated properly, behind-the-scenes protection for the humans involved in making the film was sorely lacking, with an under-experienced staff haphazardly directing untrained lions. An estimated seventy people were gravely injured, including multiple cases of gangrene and bone fractures[4], though Hedren claims the total was much lower.[5] Notable among the injuries was cinematographer Jan De Bont (future director of Speed), who was scalped by a lion mid-filming, an act that triggered a mass resignation by other members of the crew, although not De Bont himself.[6] As the film was shot in Soledad Canyon, an animal preserve housing some 132 big cats, two elephants, three sheep, and various African birds[7], a skeleton crew working for both the preserve and the film, and loyal to the Hedren-Marshall family, shepherded the project through a five-year shoot (and eleven-year production altogether).[8] The production was further rocked by inconsistent funding and severe flooding. The turbulence led to a shaky, muddled film in its final cut, in which no American distributor expressed interest, although some international release deals were negotiated in 1981.[9] The film remained largely unseen, until 2015.

Drafthouse Films, a hip indie-minded distributor rooted in the Austin-based company Alamo Drafthouse Cinemas, heard of Roar’s chaos-plagued history and decided to revitalize the film with an American release, this time stressing it as a “cult film” for raucous midnight audiences.[10] The strong, if foolish and ill-informed, humanitarian goals Marshall and Hedren brought to Roar, as an extension of their animal rights aspirations, now had to contend with a re-branding emphasizing camp pleasure in the film’s decisive failure and shocking violence. In Drafthouse’s trailer for the film, the moniker “most dangerous film ever made” was added, foregrounding the infamously troubled production. To darkly comedic effect, the trailer lists the injuries suffered by each star under their names. Tippi Hedren, broken leg. Melanie Griffith, facial reconstructive surgery. Noel Marshall, gangrene and multiple puncture wounds. This violent assemblage plays against a musical backdrop of Robert Florczak’s sentimental crooning on nature-themed songs written for the film, (“here we are in Eden…”), the juxtaposition of the idyllic against the life-threatening and thoroughly visceral. Dratfhouse’s release of Roar camps up a tragically plagued production, re-contextualizing its failures as laughable entertainment.[11] Occupying a dangerous level of taste, freely laughing at real-life injury, only heightens the intensity and pull of Roar.

One of Roar’s chief cinematic draws is the promise of unruly wildness, lions un-penned and out for savagery. In Roar,it is as if the iconic lion from the MGM logo has been released from its cage to wreak havoc on its camera-wielding captors. The lions behave both violently and tenderly, throwing Roar off balance in the creatures’ sheer unpredictable unreadability as the benevolent human intentions surrounding them collapse. Though violence is prioritized in the film’s advertising, much of the camp pleasures of Roar draw equally from its periods of tedium, from the multiple ways in which Roar struggles to cohere as its desired cinematic narrative. The film gestures towards a kind of animal camp, performative by not performing, emphasizing a basic unreadability against anthropomorphic codes attempting to ensnare and taxonomize the animal.

Sketching out a scholarly framework for understanding animal camp involves a re-positioning of animals from the margins of camp media to its spotlight. Lions make a key appearance in a film with Mae West – her 1933 comedy I’m No Angel (FIGURE 2). If camp remains nebulous to narrow definitions, with its mixture of juxtaposition, anachronism, failure, humor and fabulousness, ordered and re-ordered by different cultural sectors and performers, Mae West is at the very least the kind of pop culture diva archived and institutionalized as a locus of definitive camp (frequently, within drag circles, the “camp prizewinner,” as Clare Hemmings describes them).[12] Mae West’s camp is one of feminine exaggeration, playing up sexuality and womanliness with an aggressive wink: a claiming of oneself outside of coercive, patriarchal dominion.

FIGURE 2. Mae West and a lion in I’m No Angel (Wesley Ruggles, 1933)

In I’m No Angel West plays Tira, a circus performer and lion tamer (FIGURE 2), with characteristic pitch-perfect joke delivery, living amongst a den of thieves. Midway through the film, a particularly adventurous feat of lion taming becomes Tira’s ticket to major show business success. Tira carries a small pistol as she cracks a whip at visibly frightened and malnourished lions. West caresses the scene with her expert panache, responding to a frenzied lion with a coo of “Where were you last night?” The scene reaches its apex when Tira puts her head in the mouth of a large male lion. While other parts of the sequence are a complex forgery of editing, superimposing West onto more volatile shots of angry lions, the interaction with the final lion appears to be genuine, as West is shown patting the lethargic and low-energy animal’s head and moving open its mouth, undoubtedly using force.[13] Though language against animal cruelty was among the “Don’ts” and “Be-Carefuls” of the Hays Code in 1930, its enforcement was vague and never subject to universal standardization.[14]

Attending to camp and hailing its victories necessitates an equal awareness of its violations and aggression. Pamela Robertson, in her otherwise perceptive article noting the presence of race as an “authenticating discourse” for Mae West, attempts to defend the camp heroine across-the-board and remove her from complicity with the reductive, stereotypical roles for African American actresses as a chorus of eager, supportive maids in I’m No Angel. Robertson writes:

Thus, at the same time that West’s maids offer support for her camp performance and direct attention to her as star, they could also be seen as camping it up- overplaying their delight in the white star to point to the constructedness and inauthenticity of their supportive role.[15]

This “could also be seen as,” already worded with insecure commitment to the point, tries to save Mae West as a universal camp heroine when structures of industrial white power in 1930s Hollywood make such a reading fanciful. Camp is complicated, and the nuance of its tactical parody has to be attended to respectfully, and never generously over-honored.

The lions of I’m No Angel are a backdrop for West’s performance: mere camp accessory rather than camp itself. In a later scene of I’m No Angel, a sense of animals as accessories is made much more literal, as we see a large display in Tira’s home with small photographs of all the men she’s experienced, each photo next to a different animal sculpture. Wildness is used again as a conduit for camp, a collection promoting West’s performance while animal bodies are passive vehicles. Roar also collects lions. The screen overflows with them, a multitude of lions crammed into one small house, as if Noel Marshall couldn’t stop hunting for that sense of pure authentic animality. Perhaps Tippi Hedren was channeling West’s amorous flirtation in the 1971 LIFE photoshoot. These animal collections, operating out of an anthropomorphic rhetoric of control, face retribution in Roar, lions roaring back from the deep archive of camp for their revenge.

Some of the foundational scholarship on camp puts up harsh borders against anything ‘animal’ in camp performance. According to Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp,” an often-critiqued but ever-present piece within camp studies, “nothing in nature can be campy.”[16] Definitions of camp are frequently concerned with artifice and exaggeration, with the performative potential of the surface over any ontological tie between depth and truth. For this reason, the natural world’s traditional absence from camp archives lies on a reductive belief in nature as a site of authenticity. Recent scholarship in animal studies has shown how truly unknowable the animal world is, so much of it defined and contextualized by anthropomorphic assumptions. The “authenticity” of nature, then, is just as artificial as any other cultural script.

Sontag in her own article seems to illuminate pathways to a natural camp only to walk past them. She creates a dichotomy between Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill House and the Palace of Versailles as eighteenth-century examples of social manipulations of nature, whether in the direction of honoring a transcendentalist natural mystique (Strawberry Hill) or artificializing the natural into something architectural, even decadent (Versailles). According to Sontag, the developers of Strawberry Hill “patronized nature,” curious verbiage that envisions humanity as a distant benefactor of the natural world.[17] Versailles is a campy dream of aestheticized nature, but by casting Strawberry Hill as its opposite, Sontag creates a definition of camp that under-analyzes humanity’s relationship with the natural world. Strawberry Hill is just as curated, just as shaped to human design, as Versailles. To understand a rhetoric of camp emerging from depictions of “the natural world” is to arrive at the production of social concepts of naturalness all together, something camp has historically been used to interrogate.

But how to account for the camp position of animals? What are the ethics of ascribing performative agency to a subject that defies such presumptions? Seung-hoon Jeong writes powerfully of animals on screen as an “ontological other,” working off Bazin’s writings, that requires the basic use of cinematic montage for identification. He writes:

The animal…not merely remains an ontological other within the filmed diegesis, but becomes an ontological hybrid concerning the filming enunciation. It becomes both a black hole that penetrates different modes of the cinematic image and a quilting point that stitches the very differences. And this potential of “becoming” seems to enable the animal film to conversely reach the ideal of anthropomorphism that goes beyond its clichéd illusion formed by montage.[18]

If the animal is a cinematic creation, the object of the filmmakers’ gaze, where is the potential for camp? The agency of the camp object, against its interpretative audience and context, has been a substantive issue in camp studies since its inception. Sontag first raises the issue with her description of “unintentional camp,” supposedly the purest kind, setting up an object vs. audience position wherein the spectator’s rendering of an object is more important than the object’s own autonomy, performance, or intent.[19] This issue is magnified in scholarly renderings of camp that labor in reductive dichotomies, such as Brett Farmer, who sees camp as “transcendence,” emphasizing the performative intellect of cis gay men, elaborately de-constructing feminine identity, at the expense of women performers who are robbed of any insight or intent in their own gender performance.[20] The femme is the performance, but the camp artist generating it is securely male, and his intent and identity matter more than any resonance of the camp object itself.

Clare Hemmings offers a more redemptive paradigm of camp, with a less restrictive subject/object binary, in her piece “Rescuing Lesbian Camp” (2007). Hemmings writes with a very grounded perspective, examining lesbian incarnations of camp as they interact with butch/femme discourse. She writes:

Or camp! The gorgeous refusal to exit that condemned as vile and putrid, the holding fast in/of the abject, the loving of the loathed…Might feminine camp, in whatever body, be a refusal to believe in escape, and, in a delightful turn, an insistence on the material, the literal if you like, as itself transient? This too will pass.[21]

In this passage, Hemmings refuses to focus on camp as a rhetoric of transcendence within established binaries, writing instead of a camp that fully commits to its position of disproportionate power. She imagines a camp that can live in “the abject” without turning away from it, without relying on transcendence as a way of shuttling from one side of the heterosexist white cisgendered patriarchal discourse to the other. There is no “escaping” the remote subjectivity of the animal, and an animal camp cannot arrive somewhere new, transcendent through the power of an animating curative agency. In Roar, the oppressive dichotomies chasing camp are confounded by objects whose agency cannot be legible in human form, and whose audiences can’t claim to understand them any better than the framework of anthropomorphism does. The camp of Roar emerges through a contested text, torn between a man-made narrative of anthropomorphism and the disobedient animals such a context seeks to enfold. The performances of the film’s volatile lions lay bare the discursive roles of animals in this text reflecting a uniquely animalistic camp.

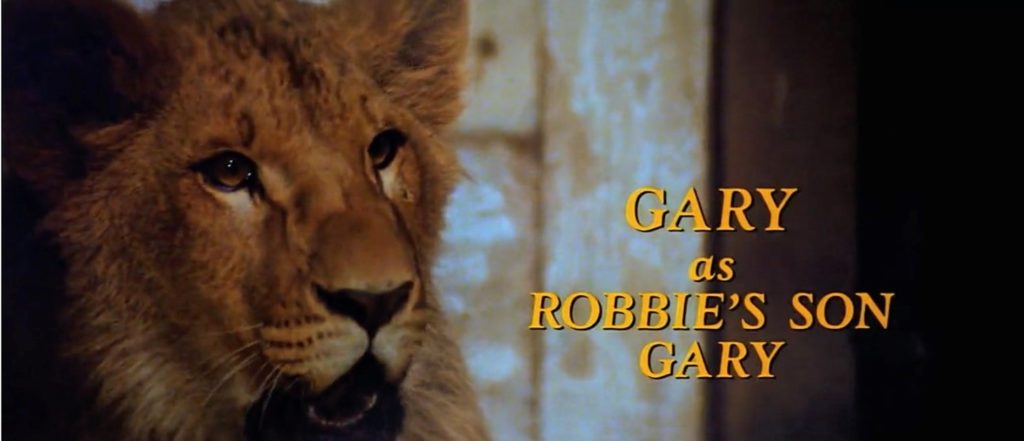

FIGURE 3. Animal Stars (Roar, Noel Marshall, 1981)

Roar is a text created in mystical longing for the natural world, fetishizing nature as the ultimate authentic. An early title card in the opening credits, over a herd of wild zebras, reads “Since the choice was made to use untrained animals and since for the most part they chose to do as they wished, it’s only fair they share the writing and directing credits.” What follows is a series of frames where some of the central lions are credited, not as writer-directors as the film misleadingly offers, but as actors. The lion stars and their roles, Roar informs us, are “Robbie as Robbie,” “Gary as Robbie’s son Gary,” and “Togar as Togar.” Through no failure on their own part, these lions have no existing celebrity profile of which to speak. The audience is not intrigued that Robbie the actual lion has the nuance and acting skill required to portray Robbie the fictional lion. Togar doesn’t even play “Togar” the whole time: the real Togar’s love for napping peacefully in the sun cut against the ferocious violence Roar’s filmmakers desired for their lead lion antagonist, and thus the more reliably vicious Tongaru was frequently used in his place.[22] Yet Roar insists on viewer awareness of the lions as performers, as playing ‘characters,’ implicated in a narrative space. This could be grounds for a generous reading, one winking slightly at the anthropomorphism inherent in the film. But in Roar’semphasis on the designation of “Robbie as Robbie,” the film reveals a faith in and attachment to its anthropomorphic fantasies of animal co-creators. It is, after all, a fantasy that the lions want to be a part of a film at all.

The lions of Roar are flesh-and-blood animals but also composites of the technical and narrative work that surrounds them. John Berger, demonstrating a keen awareness of how the concept of animals circulates in social worlds, describes animals as “the first metaphor,” noting their frequent presence in human representational systems from cave paintings to the current day.[23] In this way, narrative media functions like a zoo: arranging reflections of animals carefully controlled for a viewing public. Berger elaborates on the specific concept of the zoo that “Public zoos came into existence at the beginning of the period which was to see the disappearance of animals from daily life. The zoo to which people go to meet animals, to observe them, to see them, is, in fact, a monument to the impossibility of such encounters.”[24] Animal media can thus be part of the chain of extinction, announcing human separation from animals with narrative interpellation as a further layer of violence. This idea of animals as ephemeral, which would be taken up later by Akira Mizuta Lippit as “spectral,” emphasizes the pressing rarity of the natural world in the face of immense global development.[25] In the wake of more and more endangered wildlife, the animal takes on a heightened role of metaphoric significance in human society, a representation of the ultimate authenticity of an unsullied world.

Berger, like many writers in animal studies, displays a certain romanticism, longing for connection across the species divide. He honors and laments the passing of a “look” that could facilitate such connection, writing “That look between animal and man, which may have played a crucial role in the development of human society… has been extinguished.”[26] Were the creators of Roar similarly struck by the power of “the look,” hoping to use cinema to rekindle humanity’s capacity to care for and live with lions? Or did they hope to initiate it? Roar’s efforts at human/animal intimacy reach for something beyond the dulled, even monotonous presence of animals in human lives. Berger discusses zoos with an eye to the emptying of intensity in the lives of animals:

The animals, isolated from each other and without interaction between species, have become utterly dependent upon their keepers. Consequently most of their responses have changed. What was central to their interest has been replaced by a passive waiting for a series of arbitrary outside interventions. The events they perceive occurring around them have become as illusory in terms of their natural responses, as the painted prairies.[27]

Zoos, monuments to the disappearance of animals, perpetrate a further disappearance against animals by rendering their subjectivities even more remote, dulled to routine and captivity. Berger defines anthropomorphism as the “residue” of this process, a transformation of control and the rhetoric of animals in human discourse into a commingled archive: repairing the bridge to “the look” by defining animals completely through human interests, thoughts, and emotions.[28]

FIGURE 4: Tippi Hedren and Neil the Lion back-to-back (Michael Rougier, Life, 1971)

A particularly curious picture from Hedren’s 1971 photoshoot with Neil the lion imitates not “the look” but rather something akin to its polar opposite: lion and human back-to-back, facing away from each other. Hedren is propped up against Neil’s massive frame while staring at a newspaper, their close proximity an effort to prove a fictive easy comfort. Neil’s eyes look thoroughly alert, even on-edge, in contrast to Hedren’s casual recline. Hedren’s hair, a similar shade of brown to the base of Neil’s prodigious mane, seems to weave into the lion, a desiring of two becoming one in action, brains melding into human/animal solidarity. Yet, the distracted looks of Hedren and Neil prove an effective, unintentional metaphor for Roar: the hollow structure of anthropomorphism, flush with the warmth of idealistic humanitarian intention, rendered nonetheless foolish, condescending, and ill-prepared. Reading Tippi, Hedren’s turn to animal rights is narrativized as profound self-empowerment. Her memoir configures the act of pawning a fur coat gifted to her by Alfred Hitchcock as a rejection of the decadent powers of Hollywood, that were truly abusive to her, in favor of the wild world of animal rights.[29] The themes of Hollywood super-stardom or animal rights activism as a binary choice continue throughout her book: while choosing costumes for the characters of Roar, Hedren described the aesthetic as the “polar opposite of Edith Head,” the legendary costume designer who had created Hedren’s iconic look for The Birds.[30] In a very real way, Hedren desired rebirth through animals, ‘the look’ as discovery of a higher self. Such discoveries, as Roar exhibits, are perpetrated in clumsy ignorance of the agency and independence of the natural world.

Akira Mizuta Lippit is less hopeful about ‘the look’ between humans and animals. Lippit positions animals as a perspective of necessarily “impossible identification” that can never fully escape a human framework of understanding.[31] The inheritance he takes from John Berger’s work is clear, especially in his transposition of the disappearing animal to the spectral animal, one whose departure in the world he analyzes from a more textual vantage point. Coining the term animetaphor, Lippit analyzes how animals are always deployed to specific textual uses; even in the real world the animal remains “a metaphor made flesh.”[32] Animals’ intersection of the real and the textual is complex, and necessarily intertwined with cinema itself, the product of a supposed indexical relationship to the real that is frequently manipulated. Lippit turns to Eadweard Muybridge and the early years of cinema, writing “By capturing and recording the animals’ every gesture, pose, muscular disturbance, and anatomical shift with such urgency, Muybridge seemed to be racing against the imminent disappearance of animals from the new urban environment.”[33] Lippit utilizes the earliest of cinematic aesthetics to emphasize how quickly animals were consumed and typified, as if taxonomically classified, by the camera.

Scholars working in this tradition frequently connect textual anthropomorphic manipulations of animals to particular social relevance. Barbara Crowther, writing on the representation of wildlife in nature television, including lions, emphasizes the hold of patriarchal narratives of gender even beyond human bodies. The animetaphor is therefore not simply a controlling gesture over the animal or a nostalgia for vanishing wildlife- it can also be mobilized to specific strategies of human tyranny. Crowther writes:

It is easy enough to identify in the language of wildlife scripts the conventional patriarchal concepts that underlie them- and indeed underlie natural history itself. Beside the obvious markers, like references to the animal “kingdom” and to “Man,” there are significant distinctions made along gender lines. “Competitive” behavior and “territorial aggression” are repeatedly attributed to male animals, while females have “mothering instincts” and “protect their young.”

I bring up Crowther’s work to point to the work of animetaphors that extends beyond simply a power relationship between humans and animals. Human control over the rhetorical use of animal figures is so all-consuming, further power differentials are expressed through the language of the animal. The application of the “natural” ontological “truth” of animals to social politics of identity is also, as Crowther argues, a means of “naturalizing” prescribed roles in a patriarchal system. Texts like Crowther’s natural history programs “[validate] these assumptions as ‘natural’ in human culture by ‘finding’ them in animal groups.”[34] Anthropomorphism can be used as an authenticating power, upholding the status quo of power relations.

Returning to Sontag, it is true that camp “sees everything in quotation marks,” referring to items not as their ontological “truth” but as their performative role in a discursive system.[35] Therefore, animal studies, and studies of anthropomorphism specifically, have a “natural” relation to camp in their awareness of artificial constructs mobilized to targeted textual ends. The lions of Roar are real, untrained big cats, but in the rhetoric of anthropomorphism, their reality is part of a social value system that sutures them to human narrative codes. In a text as wobbly and malfunctioning as the film ultimately is, Roar’s lions effectively stand outside of the scraps of its broken narrative in campy grandeur.

FIGURE 5. Roar, Noel Marshall, 1981

Noel Marshall and his family, tourists in this African landscape they are simulating in their California home, play out a performance of benevolent colonial control. The Maasai people, an ethnic tribe central to Kenya and Tanzania, are thanked in the opening credits of the film, and are briefly featured, in largely the only footage of the film shot in Kenya. Noel Marshall’s Hank is introduced in this scene as a kindly doctor, bandaging the leg of a wounded Maasai woman. This sequence occurs during the opening credits of the film and strives to reinforce the authenticity of Roar’s Africa.

The film’s original songs by Robert Florczak, which also feature in Drafthouse Films’ trailer for the re-release of Roar, emphasize this neo-colonial vocabulary. Next to the more sentimental entirely English-language “Eden,” emphasizing the human/animal paradise of cohabitation, Florczak’s second song “N’ Chi Ya Nani (Whose Land is This?)” imitates an African percussive style and includes a chorus in Swahili. The lyrics of this chorus, “Whose land is this? / This is my land…,” heard both in English and Swahili, emphasize a sense of freedom and pleasure in the natural world with a surprising undertow of ownership. Tippi Hedren, in her memoir, claimed the lyrics to this song derived from East African legend, that “Whose land is this? / This is my land” was human translation of a lion’s roar.[36] Including this passage within the film’s score is emblematic of Roar’s neo-colonial intentions: bearing reference to animal roots, translated through and for human consumption.

As Roar uses animals as its vision of a natural unsullied world, so too are African natives reduced to similar ends, creating a white American mythos of Africa that is an appropriative tourist vision. Che Gossett describes blackness, particularly African blackness, as “the absent presence” of animal studies, noting the “primitive, barbaric, and bestial” themes that overrun the discursive roles of both animals and black people in white texts.[37] Roar is an anthropomorphic fantasy of romantic alliance between human and animal, but it is also a fantasy of an Africa mastered by one smart white man, geographically and socially. Yet, the white crusaders of wild Africa, typical icons of Hollywood heroism throughout time, are met with such a violent unintentional failure in Roar, that the only response can be to laugh. Camp sees the limitations of the successful white family forcibly revealed, with lions to attend to its destruction.

Roar eventually devolves to set pieces of Madeline (Hedren) and her children fleeing the big cats in different life-threatening situations. But given Roar’s use of real, untrained, non-actor lions, the division of the film between its establishing scenes—grounding the viewer in Hank’s big cat-laden world—and those in which the family is suddenly in danger, is thrillingly porous, the big cats acting more or less the same in both sections, which is to say, not acting at all. In this way the early scenes of Roar become the most instructive in terms of its anthropomorphic imagination. Early on in the film, Hank (Marshall), as the enthusiastic researcher, leads a frightened assistant, Mativo (Kyalo Mativo), around the grounds, inadvertently exposing the camp of the film. “It’s just like life, you get the funny with the tragic!” Hank encourages a trembling Mativo, as they walk Hank’s front porch, every visible spot of ground practically covered in big cat. “For my studies I have to get as close to them [the big cats] as possible!” Hank says cheerfully as a lion ensnares Hank’s leg in his meaty paws. Later, in response to a lion circling the two men, Hank optimistically relays “They like to play the ol’ cat and mouse game!” It is very difficult in Roar to distinguish between an intended shot of human/lion interaction, and a shot planned simply to get across some exposition that, thanks to an intrusive lion, has suddenly changed from the mundane to the life-threatening. This affect of instability that roars off the screen is validated by the film’s chaos-plagued production: Noel Marshall’s son John reported that his father “often refused to call ‘cut,’ even when the actors (mostly family members) cried out for help” in the name of preserving the authenticity of the animal’s actions.[38] An indelible camp image repurposed for the film’s trailer features Noel shouting “they just get a little excited!” back to Mativo as he is plowed off his feet by an onslaught of stampeding lions, cheerfully yelling “ow!,” in an attempt to salvage something clearly beyond saving.

Roar’s ultimate cinematic aesthetic is one of loose distraction. In one frame along Mativo’s tour, Hank and Mativo appear on the far left discussing a dangerous lion of the encampment named Barry, while two different lions, to whom Hank had previously referred as John and Charlie, begin fighting on the far right of screen. The lions’s roars and scratching causes Hank to stumble over his lines of dialogue, he and Mativo looking back in fear at the quick lion brawl that has suddenly erupted. The camera does not cut away, even though what appeared to be the initial premise of the shot has now failed. The feline altercation lasts less than a second, Charlie the aggressor prodding a resting John and then quickly stepping out of frame, minimizing its impact as spectacle. One could imagine a Roar where the primary draw for audiences was watching brutal lion vs. lion fights, but this theoretical source of cruel pleasure goes unfulfilled by the aimless, meandering, unscripted animals.

Roar attempts to side-step its clear failure of in-the-moment narration with an abundance of after-the-fact cinematic techniques. The animal film sentimentality Roar was after was typified by films like Born Free (James Hill, 1966), an earlier “humans loving lions” adventure and a massive success, part of a wave of media galvanizing neo-colonial desire through the mystique of African wildlife, a movement explored by Gregg Mitman in Reel Nature: America’s Romance with Wildlife on Screen (1999).[39] To bring Roar up to generic codes, the filmmakers frequently tie music to lions, attempting to stabilize them as “characters” within the text. The villainous Togar, outsider lion and threat to the pack, is scored imposingly with emphasis on savage drums. Robbie, the head of the pack, our hero lion, is announced with bright authoritative horns. Additionally, the film’s soundscape is flush with ADR (automated dialogue replacement), lines added in after filming to gloss over chaotic scenes with clear plot direction.

But ultimately, these cinematic manipulations are only partial fixes, in some cases drawing more attention to the camp of failed anthropomorphism rising from Roar’s chaos. Noel Marshall’s undaunted romantic dream of lion communication is one example. Early in the film, Roar features a lengthy “conversation” scene between Hank and a young lion named Gary. Gary is lying in the corner of a small enclave in Hank’s cabin. Hank gets down on the floor just in front of Gary, effectively cornering him in the small space. The camera is positioned right behind Hank. The following is a transcription of that scene:

Gary: [roars]

Hank: Well, hello Gary!

Gary: [roars]

Hank: [imitates roar] Why didn’t you-

Gary: [roars]

Hank: Why didn’t you go with your friends?

Gary: [roars]

Hank: Awww.

Gary: [roars]

Hank: Come on, you should go with your friends!

Gary: [longer roar]

Hank: Awww.

Gary: [roars]

Hank: Oh, come on!

Gary: [roars]

Hank: Come on, go with your friends!

Hank follows this circular conversation by leaning forward, lying down beside Gary, and forcing an embrace upon the animal. Gary sinks his teeth into Hank’s arm. Hank gets up and says “Don’t worry baby, Robbie can handle Togar! Your father’s tougher than you think!”, effectively closing the loop on a conversation that never began. Hank does a quick, fleeting imitation of a roar, to which Garry reaches out and bites Hank’s already bandaged hand. It’s worth noting that the inner conflict amongst the lion characters posited by Roar, Robbie vs. Togar with Robbie’s “worried” son Gary somewhere in the mix, obsessed with traditional patriarchs maintaining the family, echoes not only Barbara Crowther’s analysis of lions in nature television documentaries, but the circumstances of Roar’s production as well, where an authoritative father figure pushed his family beyond their limits. Roar displays, in action, humans using animetaphors to enact rituals of social domination.

FIGURE 6. Roar, Noel Marshall, 1981

After a fateful encounter with two lion poachers and many dangerous set-pieces, the screams of Roar are replaced by laughter as the film reaches an artificial happy conclusion. Hank returns to his family’s aid and changes their view of lions with simple instructions—“Don’t hit him, hug him!” to his son Jerry, wrestling with a tiger in the water.[40] Moments earlier played as the life-threatening crises that they were are re-contextualized as sentimental ending notes, structured by the musical score and the human actors’s ever-ready naive enthusiasm. After knocking Hank into the river off a tree trunk as a playful comeuppance for the danger he’s put the family through, Madeline is pushed into the water as well by a curious lion, the family overcome with laughter. The remaining five minutes of the film strive for the same ideal of integrated human/animal intimacy as the LIFE photoshoot, indulging in shots of the family bonding with lions, rolling over the same idealistic ballads by Robert Florczak used for the trailer of the 2015 release.

But what is all this laughter about in Roar? Henri Bergson, similarly to Sontag, excludes “nature” when describing the discursive construction of comedy, writing “the comic does not exist outside the pale of what is strictly human…You may laugh at an animal, but only because you have detected in it some human attitude or expression.”[41] For Bergson, laughter is a social mechanism of control, a “social gesture” keeping normative behavior stable.[42] Therefore, when extrapolated out of the human world, laughter must still be following social codes. For the Hedren-Marshall family the laughter in Roar might be read as anxious: the creeping nervousness of a project gone terribly awry and danger looming around every corner. But for the audience, the laughter functions much the same. Camp exists in borderlands and peripheries, and in Roar that camp-anxiety erupts at the limits of anthropomorphism against the realm of impossible identification.

Tippi Hedren continues to commit earnestly to animal rights and protection, with the Shambala Preserve (the location of Roar, renamed from Soledad Canyon in 1980[43]) a rigorous institution supporting vulnerable wildlife. Her humanitarian work has refined itself since the heady, idealistic days of her and Noel Marshall’s lion love dream. Roar’s camp parody exposes the limiting anthropomorphism that is often behind such gestures, and the chaotic work at the human/animal threshold to establish generic narratives. Though the film is a “failure,” Roar has ironically found a way to use the historically aggressive machinery of cinema to results worthy of the king of the jungle. The lions of Roar possess an affect of radical inhabitance, caught on film and slipping through and outside of the trap of anthropomorphic human narrative.

Sean Donovan is a doctoral candidate in Film, Television, and Media at the University of Michigan. His scholarly work has been published in the journals The New Review of Film & Television, Somatechnics, and Gender Forum.

Notes

[1] Ben Cosgrove, “Something Wild: At Home with Tippi Hedren, Melanie Griffith, and a 400-Pound Lion,” Time, 17 October 2014, http://time.com/3545926/something-wild-at-home-with-tippi-hedren-melanie-griffith-and-a-400-pound-lion/.

[2] Tippi Hedren with Lindsay Harrison, Tippi (New York, NY: William Morrow, 2016), 107-108.

[3] Hedren, Tippi, 222.

[4] Lindsay Bahr, “‘Roar’: ‘Most Dangerous Movie Ever Made’ Charges Into Theaters,” The Hollywood Reporter, 16 April 2015, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/roar-dangerous-movie-ever-made-789230.

[5] Kate Erbland, “‘Roar’: Tippi Hedren Reveals How Many People Were Actually Hurt While Filming Legendarily Insane Movie,” Indiewire, 18 November 2016, https://www.indiewire.com/2016/11/roar-tippi-hedren-people-hurt-insane-movie-1201748012/.

[6] Hedren, Tippi, 187.

[7] Hedren, Tippi, 179.

[8] Erbland, “‘Roar’: Tippi Hedren Reveals…”

[9] Hedren, Tippi, 229.

[10] Bahr, “‘Roar’: ‘Most Dangerous Movie Ever Made’…”

[11] Movieclips Indie, “Roar Official Re-Release Trailer 1 (2015) – Melanie Griffith Movie HD,” 10 March 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cny_D50Rr44

[12] Clare Hemmings, “Rescuing Lesbian Camp,” Journal of Lesbian Studies, 11:1/2 (2007), 159-166, 161.

[13] I’m No Angel, dir. Wesley Ruggles, Paramount, 1933.

[14] Kathleen M. Peplin, “Construction and Constraint: The Animal Body and Constructions of Power in Motion Pictures,” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2016).

[15] Pamela Robertson, “Mae West’s Maids: Race, ‘Authenticity,’ and the Discourse of Camp,” Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject: A Reader, ed. Fabio Cleto. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999. 406.

[16] Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’,” Against Interpretation and Other Essays (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1966), 279.

[17] Sontag, “Notes on Camp,” 280.

[18] Seun-hoon Jeong, “André Bazin’s Ontological Other: The Animal in Adventure Films,” Senses of Cinema, Issue 51, July 2009, http://sensesofcinema.com/2009/towards-an-ecology-of-cinema/andre-bazin-animals-adventure-films/.

[19] Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’” 282.

[20] Brett Farmer, “The Fabulous Sublimity of Gay Diva Worship,” Camera Obscura, 20:2 (2005), 164 – 195.

[21] Hemmings, “Rescuing Lesbian Camp,” 164.

[22] Hedren, Tippi, 190.

[23] John Berger, “Why Look At Animals?,” About Looking (New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1980), 7.

[24] Berger, “Why Look At Animals?,” 21.

[25] Akira Mizuta Lippit, Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota press, 2000), 1.

[26] Berger, “Why Look At Animals?,” 28.

[27] Berger, “Why Look At Animals?,” 25.

[28] Berger, “Why Look At Animals?,” , 11.

[29] Hedren, Tippi, 168.

[30] Hedren, Tippi, 180.

[31] Lippit, Electric Animal, 181.

[32] Lippit, Electric Animal , 165.

[33] Lippit, Electric Animal , 185.

[34] Barbara Crowther, “Towards a feminist critique of television natural history programmes,” Feminist Subjects, Multi-Media: Critical Methodologies, eds. Penny Florence and Dee Reynolds (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1995), 127-146, 128.

[35] Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’” 280.

[36] Hedren, Tippi, 87.

[37] Che Gossett, “Blackness, Animality, and the Unsovereign,” Verso, 8 September 2015, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2228-che-gossett-blackness-animality-and-the-unsovereign.

[38] Bahr, “‘Roar’: ‘Most Dangerous Movie Ever Made’…”

[39] Gregg Mitman, Reel Nature: America’s Romance with Wildlife on Film (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999). 2nd edition (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2009).

[40] Soledad Canyon housed two tiger cubs that Marshall wanted to be part of Roar. He and Hedren argued over the logic of tigers in the film considering its African location (Hedren, Tippi, 133-134).

[41] Henri Bergson, “Laughter,” Comedy, ed. Wylie Sypher (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 3rd Edition, 61-146. 62

[42] Bergson, “Laughter,” 73.

[43] Hedren, Tippi, 228.