Touch, textures, and intensity ——— Analyzing Fight Club

from the perspective of embodied spectatorship

Simin Nina Littschwager

Oscillating between intense corporeal experiences on the one hand, and various modes of physical and psychological alienation on the other, Fight Club is a film about affective extremes. The character-narrator’s (Edward Norton) disengagement from the world is portrayed not only as a process of mental dissociation – culminating of course in the subconscious creation of his alter ego Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) – but also as a pathological bodily state. The latter is characterized most prominently by insomnia as well as by a desire for substantial physical pain and transgressive physical encounters, and further by a fundamental sense of tactile estrangement that runs deep throughout the entire film. Fight Club is a tale of, quite literally, being out of touch with the world and with others, and of regaining this touch. As such, it demands a mode of viewing that is equally sensitive to the film’s narrative and broader socio-political themes as it is to the textures, surfaces and materialities that constitute its fictional world, along with the tactile experiences they engender. Looking at the interrelationship between touch, textures and embodied intensity, this essay suggests that Fight Club crucially plays on our own sense of touch in engaging us with its main character and his predicament.

Tactility and corporeality are indeed some of Fight Club’s key themes. There are a number of apparent examples that immediately come to mind: the graphic depictions of sex, violence and masculinity; the productive function of pain during the actual fight scenes and elsewhere; and not least the distinctly physical appearance of Tyler himself. Yet the film is interspersed with a much wider range of affective moments and sensuously charged situations, and the narrator often frames his experience in explicitly bodily terms. For instance, after discovering a collection of essays written in the first person from the perspective of an organ (“I am Jack’s medulla oblongata. Without me Jack could not regulate his blood pressure, heart rate or breathing.” – “I am Jack’s colon. I get cancer. I kill Jack.”) he uses similar figures of speech to express his emotions, in particular those that are negative and suppressed (“I am Jack’s raging bile duct.” – “I am Jack’s smirking sense of revenge”).[1] Such latent preoccupation with the viscera has already surfaced earlier in the film when Jack, under a false name and faking various illnesses, visits support groups because they provide him with relief from his insomnia. He deliberately chooses groups that have to do with internal bodily diseases such as cancer or parasites, whereas he casually ignores those that deal with psychological trauma such as the “incest survivors group.” Notably, it is not primarily the act of listening to other people’s accounts of pain and suffering that soothes his own condition, but rather the one-on-one rituals at the end of each session. While hugging each other in pairs, members are encouraged to “share yourself completely”– their mutual experience being shared not through words but through touch.

Tactility, often sexualized yet altogether gentle and affectionate, also infuses many of Jack and Marla’s encounters: from the first time they meet and embrace in a support group meeting, to the moment when Marla tests Jack’s feelings for her under the excuse that she needs her breasts checked for lumps, and lastly to the film’s final image of them holding hands in front of exploding skyscrapers. Nancy Bauer, writing about the interpersonal aspects of Jack’s insomnia, his emotional detachment, and his inability to either experience or express feelings, argues that Fight Club is about “the passionate question of what it means to recognize another person’s existence” and find the right distance to them, which she sees fulfilled in this final image.[2] Yet in addition to the “profound separation from other people” that Bauer observes as a result of his insomnia,[3] Jack’s predicament is rooted in an even deeper reaching alienation from the world, one that is essentially tactile and embodied. The film therefore is just as much about the question of finding the right way of touch and letting oneself be touched by another person.

The thematic prominence of corporeality, touch and affect makes Fight Club an interesting case study to revisit from the perspective of embodied spectatorship. On the one hand, Fincher’s film has been scrutinized in particular for its representation of sexuality and violence and, in relation to that, the crisis of masculinity set in the context of corporate and consumer culture in the US. On the other hand, discussions of Fight Club and spectatorship have mostly come from narratological and cognitivist perspectives. For instance, Eva Laass gives a detailed analysis of the film’s effective play with focalizing strategies, discussing it as an example of unreliable narration in cinema.[4] Others have focused on the notorious twist in which we learn that Jack and Tyler are in fact the same person.[5] Yet just like the story itself encompasses a much wider scope of embodied experiences as outlined above, Fight Club’s capacity to elicit embodied responses from viewers extends beyond the visual presentation of bodies and corporeal encounters on the screen. Mark Hagood, who focuses on the use of Foley in Fight Club, suggests that sound works in such a manner. Performing what he terms a “transductive analysis [that] inquires into the sonic transmission of affect,”[6] Hagood argues that sound – in particular the punching sound during the fight scenes – not only “is an essential signifier of the connections between human bodies on-screen,” but “is also an essential connection between the representational bodies on-screen and the body of the ‘viewing subject’.”[7] However, even though he acknowledges the embodied nature of film viewing, he contends that, “since there is no haptic element to film, sound becomes an essential body double for touch.”[8] Yet this position can be disputed, following haptic theorists such as Vivian Sobchack, Laura Marks and Jennifer Barker.

According to Sobchack, for example, we are “cinesthetic subjects,” whose vision and hearing in cinema are always cross-modally informed by the other senses such as touch.[9] And as this essay will suggest, our tactile engagement with a film, our ability “to commute seeing to touching and back again without a thought”[10] in fact plays a key role in understanding Fight Club as “a film about human contact.”[11] Not least the fact that many reviewers employ body-based metaphors to describe the film’s aesthetic suggests that Fight Club’s affective appeal – or its repelling effect – indeed stems from a wider range of embodied cinematic experiences. For instance, one reviewer comments on the film’s “blistering, hyper-kinetic style,”[12] and another describes it as a “sustained adrenaline rush of a movie.”[13] If we bear in mind Barker’s definition of cinematic tactility, which comprises of haptic, kinetic and visceral structures of embodiment,[14] then these figures of speech can be taken literally rather than metaphorically, supporting the notion that Fight Club mobilizes a range of our bodily registers in relaying to us the tactile dimension of Jack’s alienation from the world.

To account for the tactile involvement of the viewer in Fight Club, a textural – rather than textual – analysis of the film is a most suited approach. Tracing a film’s “tactile and tangible patterns and structures of significance,” as Barker describes this analytical method, reveals how meaning emerges as part of the embodied experience of watching a film, rather than pointing out the narrative clues that we might pick up on in a more reflective mode of engagement.[15] A film’s texture, in this context, is understood as “something we and the film engage in mutually, rather than something presented by the films to their passive and anonymous viewers.”[16] With a greater emphasis on a film as an aesthetic object, Lucy Fife Donaldson suggests that the notion of a film’s texture is a comprehensive concept that applies to “both fine detail and composition”[17] and the overall “evocation of touch and surface, of the materiality of a film’s work.”[18] Yet like Barker, Donaldson too stresses the implications of analyzing a film’s texture for spectatorship when she writes that:

[it] has an important connection to its sensory dimension, concerning the resulting qualities of a surface that we might perceive through touch or anticipate through sight and sound. As such, texture expresses the sensuous “feel” of a medium, material, or environment, and thus connects with the subject of touch. This in turn invites consideration of affect, and of the sensorial relationships between film and spectator.[19]

Analyzing a film’s texture does not mean ignoring its narrative altogether though. Rather, as Ian Garwood points out, textural analysis “is sensitive to the sensuous capacities of cinema [and] considers how this might deepen, rather than distract or supersede, the viewer’s interest in a film as a distinctive fictional world.”[20] Put differently, paying attention to a film’s texture as a critical method allows us to consider not only the role of texture within the film itself, but also how its “details, patterns, and overall shapes; the density and sparsity of action, the flow or friction of a camera movement or montage sequence”[21] engages us as embodied viewers, or “cinesthetic subjects,” to use Sobchack’s term. Thus in the context of Fight Club, looking at the interrelationship between touch, textures and embodied intensity allows us to think about how our own sensuous proximity to the film helps us make sense of the story it tells, beyond the representation of bodies on screen.

Tactile intensity in Fight Club’s opening sequence

A good place to start this textural exploration of Fight Club is the film’s opening sequence. We might follow an approach common to much haptic scholarship and single out a key moment and “[use] the texture in a moment to understand and value the texture of a moment” as well as relate that moment to the film’s broader thematic and narrative.[22] According to Martine Beugnet, doing so “allows us to engage with the films as thinking processes … not to merely think about film, but to think with and through film.”[23] Moreover, as Laura Marks has observed, commercial narrative cinema often uses haptic images – images that deny an easy sense of optic orientation and invite a close mode of viewing instead – “as though to slowly ease the viewer into the story.”[24] However, while Fight Club’s opening sequence indeed draws on the tactile registers of the viewer’s body, it is all but a slow and gentle transition into the world of the film: Taking us on a nauseating ride through the dark, wet and densely textured world of Jack’s brain, it provides a haptic entry point in the form of a rather rough and bumpy ride.

The CGI-effected tour de force begins in the amygdala (the region associated with fear and emotional responses), then continues backwards and at fast pace through a network of rapidly firing neurons and later along Jack’s sweaty forehead, and ultimately ends atop a gun barrel revealed to be stuck in his mouth. Thematically, this opening introduces us to some of the film’s core issues such as mental illness and emotional disturbance, foregrounding the tensions between the mental and the physical, interiority and exteriority, emotion and intellect, which all define Jack’s struggle throughout the main part of the film. It further points to Tyler’s existential ambiguous status as a figment of Jack’s mind-brain, and, as Anthrin Steinke suggests, makes visible his association processes and rhizomatic thought-patterns that underlie the entire narrative as an organizing principle.[25] However, while such a reading is perfectly feasible, this emphasis on cognitive aspects alone does not account for the affective and sensory impact the sequence has on spectators.

Experientially, the immersive brain ride yields an unsettling somatic effect. Immersing us into the cerebral world of Jack’s brain with extreme microscopic detail, Fight Club’s opening sequence not only exceeds our own perceptual and bodily capacities to a significant degree, it also leaves us with little but our own sense of tactility in order for us to make sense of this space. For most viewers, the interior of a human brain is not routinely familiar, and so it is only later that we come to identify this mysterious setting as the innermost regions of Jack’s brain. Initially, its disorienting geography is as alien as the unchartered landscape of a planet in a science-fiction film, and its uncomfortably strange sounds, shapes, textures and surfaces evoke sensations that range from haptic curiosity to revulsion, from fascination to disgust.

Figure 2: Fight Club‘s opening sequence takes us to a place that is as alien as a planet in a science fiction film.

Even prior to any visual orientation, Fight Club’s opening invokes a mode of hearing that can best be described as haptic. In her brief discussion of sound, Marks suggests that haptic sounds are registered by our ears as an indistinct “aural texture,” rather than “aural signs” that we consciously listen out for.[26] This notion of “aural texture” perfectly captures the beginning of Fight Club where, once a thirty-second display of studio logos has passed, electronic sound effects of no discernible origin arise out of the near pitch-blackness of the screen. A strange gurgling is followed by a crackling white noise, a brief succession of musical beats and a scratching sound reminiscent of a record being manipulated on turntables. The undifferentiated origin of these haptic sounds stirs a certain unease – a good reminder that cinematic tactility is not necessarily a pleasant experience – yet what truly makes our skin crawl is their uncanny proximity. According to Steven Connor, “The sound of the screen is not ‘on’ the screen, but in the listener.”[27] The transgressive, perhaps even invasive quality he ascribes to sound thus defies the notion of the skin as a barrier, and it captures the intrusiveness of Fight Club’s aural texture, a bodily sensation that almost feels too close for comfort.

This latent sense of disquiet is by no means mitigated when faint light lets us catch a first glimpse of a peculiar surface that neither our eyes nor any other part of our perceptive body can readily identify. Before long the camera starts pulling away, not allowing much time for our eyes to dwell on the dark and fuzzy, moist and murky looking textures gliding past. A welcome light source in this dark environment are the credit titles, behind which in regular intervals little luminescent, blue and white clouds pop up to disperse the white letters and then evaporate along with them. Accompanied now by fast-hammering Drum & Bass music, the camera moves at a moderate pace at first, narrowly floating through a gap between two horizontal planes. Suddenly, a gaseous black substance spouts out from a number of crater-like holes, and as if triggered by this mysterious emission, the camera swiftly accelerates backwards. Closely riding over a crest and then maneuvering a left-hand bend in a nauseating move, it then starts swerving and skirting at varying speed along, and right through, an entangled network of fibers and pathways. Throughout this ride the camera remains at a near impossible physical proximity to its surroundings, and yet it pursues its course remarkably smoothly, without ever bumping into something and completely unperturbed by the flurry of tiny particles whirling and buzzing around.

As mentioned earlier, Barker’s definition of cinematic tactility encompasses touch at the surface of the body as well as the deeper structures of embodiment, a notion that sheds light on our ambivalent experience when first encountering the haptic strangeness of this cerebral setting. Referencing Walter Benjamin, Barker notes how touch and the feeling of disgust are closely related.[28] This helps explain how here, and throughout the sequence, the shallow depth of field produces a mode of haptic visuality that effects a sense of unease and aversion. Without knowing what exactly it is that we are looking at, the obscure surfaces – some of them look furry, while others appear to be of a sticky viscosity – are something we would rather not feel against our skin. Our perceptual unease in this dark and strange environment is fortified through the fact that the film’s backward movement is at odds with our own body’s proprioceptive orientation towards the world. For as Barker suggests, we and a film engage in a gesture of mutually shared kinesthetic empathy that finds its most basic expression in a shared inclination to move through the world upright and in a forward direction.[29] Thus while the motion of the camera evokes the kinetic pleasure of the ride, it simultaneously unsettles our sense of direction. In short: it is not just that we do not know where we are – we do not know where we are going either.

Once the camera exits the cerebral labyrinth of Jack’s brain through a hair follicle, in a smooth and effortless passage only CGI can provide, we may begin to realize what kind of space we have just been traveling through. Sobchack has famously described how her fingers carnally knew what she saw in the opening shot of The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993) before she consciously identified a blurred close-up of fingers.[30] A similar sense of haptic recognition may befall us when we are watching this moment in Fight Club’s opening sequence: our skin, “intensely sensitized to the texture and tactility … figured on the screen,”[31] is able to identify the grotesquely magnified pores, beads of sweat and facial hair long before our eyes get accustomed to the defamiliarizing effect of the microscopic enlargement. Only when the camera continues moving backwards along the metal rail that we soon recognize is the barrel of a gun, its cool and smooth surface palpably different to the sticky textures of the body, it dawns on us that we have just been traveling through the interior spaces of a brain. Having become conscious of the reality of this innermost yet alien location, some viewers may well feel a sense of relief when, finally, the ride ends and a seamless focal shift reveals the clearly identifiable image of a human face.

Figure 4: Jack’s magnified skin elicits a sense of haptic recognition near the end of Fight Club‘s opening sequence.

While this has brought us to the end of the cerebral ride, no discussion of Fight Club’s opening sequence in terms of its bodily affect would be complete without addressing the musical title track. The Drum & Bass music, composed by the Dust Brothers, constitutes an additional layer of the film’s aural texture. Far from attuning its viewers gently to the movie, the fast hammering music immediately follows the haptic sounds mentioned earlier. Syncopated break beats and intersecting drum loops – typical characteristics of Drum & Bass – create a nervous kinetic energy. Lower frequency beats impel the 4/4 rhythm throughout, and at several moments high-pitched screeching and shrieking sounds pierce through the darkness. In combination with the stroboscopic lightning flashes and the phosphorescent light pulsating through some of the fiber cables, this music evokes an atmosphere reminiscent of the flickering frenzy of an underground techno-club. Not only does it significantly contribute to the accelerated feel and velocity of the ride, but it also works on a visceral level, and thus engenders the deepest mode of what Barker has defined as cinematic tactility.

Similar to Steven Connor’s sonic conception of sound, Don Ihde describes how aural phenomena get absorbed by, and become meaningful through, our whole body. He writes:

Sound permeates and penetrates my bodily being. It is implicated from the highest reaches of my intelligence which embodies itself in language to the most primitive needs of standing upright through the sense of balance which I indirectly know lies in the inner ear. Its bodily involvement comprises the range from soothing pleasure to the point of insanity in the continuum of possible sound in music and noise.[32]

Echoing Barker’s description of the “visceral resonance between film and viewer that … moves through the skin and the musculature to get here,”[33] Ihde’s account of the full-bodied experience of sound points to the deep-seated connection between music and the body.[34] Moreover, Ihde makes it possible to suggest that Fight Club’s title track might even affect our vestibular sensitivity – the sense organ he mentions that lies in the inner ear – and thus potentially amplifies the disorientation generated by the brain ride itself. For relative to the level of loudness of the remainder of the film, it is clear that the music in the opening sequence is meant to have a forceful impact in terms of both volume and intensity. Its intent, however, is not to drive us to the point of insanity before the film even begins. Rather, it anticipates the embodied intensity that Jack requires in order to regain his touch with the world, and this can be said of opening sequence altogether. Arousing our senses, it makes clear that Fight Club is all about experiencing the intensity of a moment. It is almost as if we – just like Tyler before his first fight with Jack – had cheerfully proclaimed upon entering the theatre: “I want you to hit me as hard as you can!”

“The insomnia distance of everything” – Tactile alienation and the productive function of disgust

In Chuck Palahniuk’s novel Fight Club, on which the film is based, the narrator links his chronic sleep deprivation with his tangibly alienating surroundings, describing it as a mode of tactile hyper-sensitivity that keeps him both perceptually and emotionally removed from his surroundings. In a chapter in which he recounts his support group visits, he says: “This is how it is with insomnia. Everything is so far away, a copy of a copy of a copy. The insomnia distance of everything, you can’t touch anything, and nothing can touch you.”[35] There is a shortened and slightly modified version of this statement in a scene early on in Fincher’s adaptation of the book. When Jack takes us back to the ultimate beginning of his story with a second flashback, he explains in voice-over: “With insomnia, nothing is real. Everything is a copy of a copy of a copy.” This statement is illustrated with a scene at his workplace during which, notably, the first subliminal shot of Tyler flickers by. Given also that one of the film’s most remarkable features is the highly effective play with focalizing strategies that prevents us from realizing that Tyler is merely a figment of Jack’s mind, it may seem that Fincher and screenwriter Jim Uhls have indeed shifted the emphasis from touch to the question of reality in adapting Fight Club for the screen. Yet while it is true that the tactile dimension of Jack’s insomnia never gets as explicitly verbalized in the film as it does in the book, it has not been dispensed with altogether.

Fight Club – the film – draws on an array of cinematic means in order to convey Jack’s tactile detachment from the world, and in doing it so mobilizes our corresponding perceptual registers throughout. The above-mentioned scene, for example, begins with an extreme close-up of a disposable Starbucks coffee cup oddly sliding past and illuminated by the characteristic flashing of a photocopy machine. Next, a mid shot shows Jack standing at a copy machine, opening his eyes as if startled and then staring vacantly further afield past the camera. With a sudden shift of distance and depth of field, the film then cuts to a point-of-view long-shot of an open plan office in which a number people stand at copy machines in near identical posture, each of them staring in another direction and holding a disposable coffee cup in their hands. While this last shot neatly illustrates the notion of infinite duplicates, where “everything is a copy of a copy of a copy,” the alteration of camera distances in this scene works as a tangible expression of the “insomnia distance of everything” as described in the book. Barker notes how such unmotivated cuts and reframings can have a bodily jarring effect for viewers.[36] Juxtaposing emotional distance and physical proximity, the film relays the alienating effect of Jack’s surroundings, where what we see is either strangely far away or uncomfortably close.

A similar play with distances occurs during some of the support group meeting scenes. Here, Jack’s inability to feel emotionally connected with others is often amplified through the way the film itself seems relationally at odds with its main character. In particular, when Jack interacts with other people, the film often takes a distant and observant glance towards him. At other times the camera pretends to take on Jack’s point of view amidst the support groups, its attentive gaze directed at the person speaking, while Jack’s continuing voice-over belies his feigned interest in the other person – yet only to pan across the room and reveal Jack at the other end, accentuating not only the distance between Jack and other people but also the one it maintains between him and us.

During these early stages of the film, the life that Jack leads is that of a consumer and white-collar professional. Consistent with this life-style, he lives and works in a world that is characterized by clean, shiny, artificial and glossy surfaces, a tactile environment that David Howes has described as typical of consumer capitalism, where “Everything seems designed to create a state of hyperesthesia in the shopper.”[37] The office Jack works in, the airports and hotels he visits on his business trips, the pre-packaged convenience products he gets served, the ad-shells he sees in the streets, and not least his condominium on the fifteenth floor of a “filing cabinet for widows and young professionals” – each and every place he encounters has an intensified, smooth yet plasticky feel to it. Even his “inner cave” which he explores during guided meditation fits into this textural pattern: all but a place of comfort, his mental refuge is an ice cave with blindingly white walls and a slippery ground, where his spiritual “power animal,” a penguin, suggests with a chuckle: “Slide!” An almost sterile counterpart to the dark and murky interior of the brain, this bright and cold space is indicative of Jack’s tactile alienation from his surroundings. And it is easy to see how an existence in this kind of environment, where everything appears smooth and glossy on the outside but lacks substance and any personal touch, can lead to a – quite literal – de-tachment from the world. This is a life characterized by triviality and superficiality, where both people and things are defined through nametags and brand names, and where no touch leaves a personal trace, no contact is permanent, and nothing ever holds and sticks.

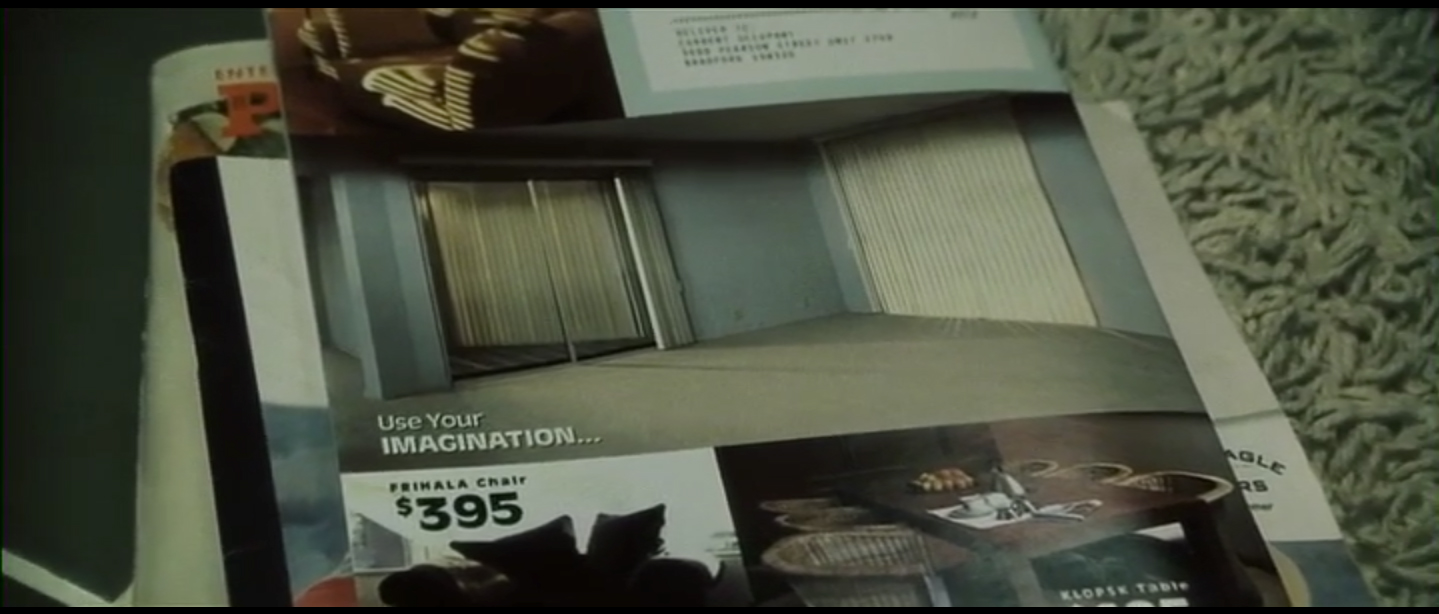

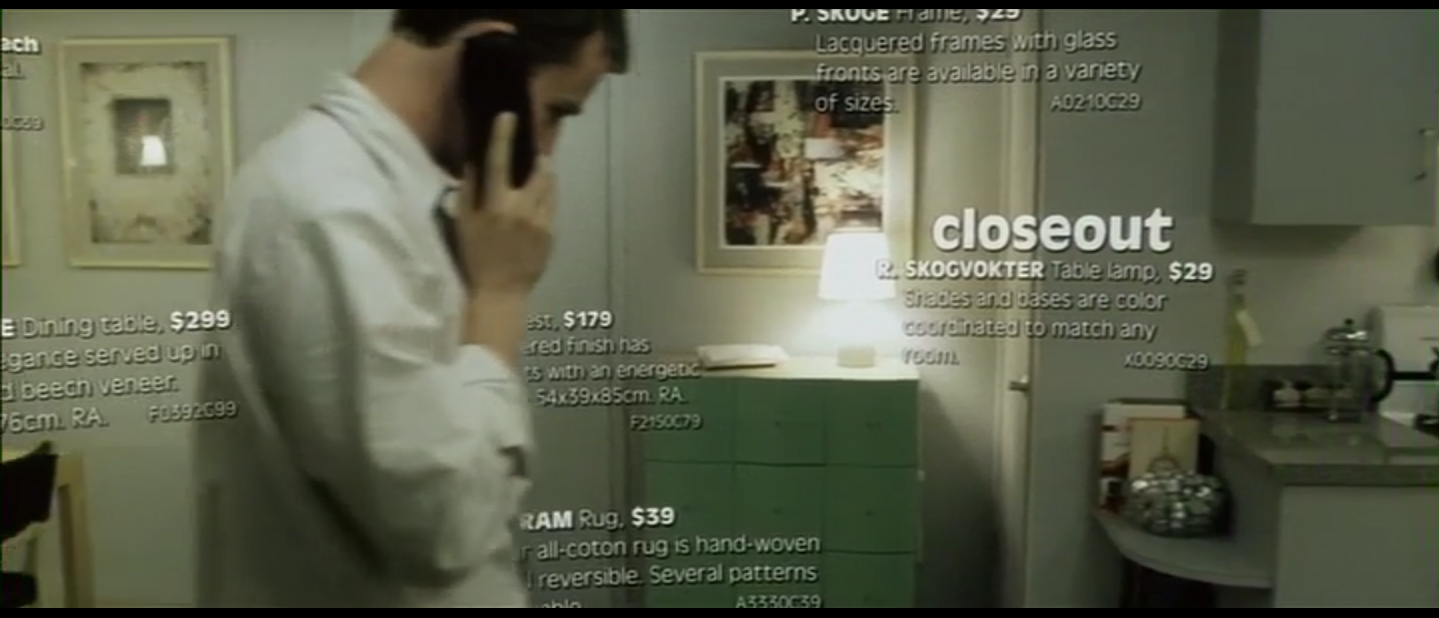

While close-ups often help us get the feel for this world and its alienating effects, perhaps the most haptically charged moment in this respect is an intricately layered spatial montage sequence in which Jack relates how buying mass-produced designer furniture for his apartment is the only activity he finds fulfilling. As soon as Jack begins describing his “IKEA-nesting-instinct,” a low angle camera starts gliding past some polished surfaces of a bathroom and towards Jack, who is browsing through a furniture catalogue whilst sitting on the toilet. The camera is drawn in particular to the illustration of an empty room on the catalogue’s back cover with the suggestive caption “use your imagination.” This illustration takes up the entire screen with a dissolve, a technique that Barker considers as a gesture of cinematic caress that “moves us from shot to shot by allowing the surface of one image to press against the other as they merge slowly.”[38] In that way the film invites our own sense of touch to feel the glossy tactility of a catalogue page and its shiny promises, a smooth surface our own fingers most likely would have enjoyed running along countless times. Suddenly, as if Jack’s imagination or perhaps even the film’s own was brought to life, furniture items start appearing in the image of the empty room from the left to the right. Each of them is accompanied by a caption that is typically found in a sales brochure. The image becomes even more baffling when the camera starts rotating across the room to the right and Jack enters the frame and walks across the room in front of the captions, all the while his voice-over is still detailing his furniture obsession. After a cut, the following shots show Jack in the very same room, amidst the very same furniture items.

The obfuscation between the separate diegetic layers in this sequence creates what Phil Powrie has called a “meta-diegetic and haptic moment, which takes us out of time and space into embodied feeling,”[39] and it does so in the most direct sense. Discussing a moment of similar diegetic instability in François Ozon’s 5×2 (2004), Powrie extends Marks’ concept of images and visuality respectively. He describes how the temporary arrest of diegetic coherence disrupts narrative immersion and incites a more reflective engagement, yet one that is nonetheless founded on embodiment rather than mere cognition.[40] This notion of a “haptic moment” captures the peculiar distancing effect elicited by the IKEA-nesting-instinct sequence. It is not only that, despite the homely atmosphere that the warm lamps and colorful patterns are meant to provide, everything both looks and feels a little too perfect to be a real home. Even though we see Jack walking among the furniture items, both the caption prints and the film’s refusal to move itself through the room defy the illusion of perspectival depth and thus obstruct our sense of spatial immersion. Almost eliciting a state of tactile hyperesthesia in the viewer, the film evokes a felt difference between the diegetic layers, and between a catalogue page and a real, three-dimensional space – and without having to think about it we understand that Jack’s condominium is neither a lived-in, nor an inhabitable home.

In contrast to Jack’s polished and neatly furnished apartment and the glossy life-style products that permeate his consumer life-world, the textures and surfaces that Tyler is associated with could hardly be more opposite. Tyler lives in a dilapidated and boarded up house in an out-of-the-way industrial area, elsewhere tellingly referred to as “a toxic waste part of town.” Already the name “Paper Street” is evocative of a more concrete and tangible location. However, this is not an inviting place in the conventional sense. The minimal furnishings – blank mattresses, pieced together chairs and tables, second-hand kitchenware – might be attributable to Tyler’s anti-consumerist stance. But one would be hard pressed to find any ideological justification for the filthy and run-down state of the place. The walls are coated in multiple layers of dirt and peeling wallpaper. Most surfaces are covered in some unidentifiable smudge, smut or smear. Stacks of old newspapers and magazines fill several rooms. Water stands knee-high in the basement and interferes precariously with the switchboard. There are numerous leaks, and a smell of dampness hangs palpably in the air.

More than just a plain shift of locales, moving in with Tyler is Jack’s first step to find a way out of the estrangement his condo-lifestyle had fostered. Despite pulling grimaces and making a number of scoffing remarks about Tyler’s “shithole,” Jack acquaints himself rather quickly with the house on Paper Street. Not only that, but he explores it with an increasingly sensory awareness, commenting, for example, on the “rusted nails to snag your elbows on,” the olfactory qualities of the house – “the fart smell of steam, the hamster cage smell of wood chips,” “the warm stale refrigerator” – and the way the house itself seems organically integrated with its environment: “Rain trickled down through the plaster and the light fixtures. Everything wooden swelled and shrank.”

Jack’s perceptual curiosity is paralleled by the film itself. Tyler’s house is surprisingly well lit, a notable contrast to the otherwise dark and gloomy atmosphere, and the camera explores it with much fascination for detail, traveling up and down staircases, traversing adjacent rooms, closely inspecting the grimy walls or dwelling on filthy fabrics. These cinematic tactile explorations occur in particular during the ample time that Jack and Tyler spend drinking and talking in the bathroom. The camera lingers closely, for example, on the discolored water spewing out of a rusty tap of a stained sink, while the characters engage in activities that are commonly associated with bodily hygiene, such as teeth brushing, bathing or washing, and that often involve bare skin. Our own skin understands perfectly well the dangers of contagion lurking in each and every corner here, and yet we find that our gaze often gets stuck on these rough and dirty surfaces. Paradoxically, even though Tyler’s house may not be the most pleasant place in the traditional sense of a home, it nevertheless feels much more real in its dirty stickiness than the artificial and sterile surfaces of Jack’s apartment.

In addition to residing in this “toxic waste part of town,” Tyler is drawn to organic matters commonly associated with disgust and revulsion, such as visceral fluids and bodily waste products. To make matters worse, his fondness for obnoxious substances and potentially contagious encounters is not limited to his own body. He freely violates cutaneous boundaries, contaminating restaurant food with his own bodily fluids such as sperm, urine and mucus, or spilling and smearing his blood onto the face of another man during a fight. Defying his profession as a soap maker, he himself exhibits no fear of bringing his naked skin in direct contact with even the most tainted, possibly contaminated of substances and surfaces. In one notable instance he and Jack steal fat from a liposuction clinic to use it as a component for making soap, retrieving it out of a container labeled “infectious waste.” One of the bags tears open as Jack passes it onto to Tyler over a barb wired fence. Yet instead of shying away in disgust like most of us would, Tyler reaches out for the gooey stuff oozing out of the bag with both his bare hands, an attempt to retrieve some of the valuable ingredient. Witnessing the scene from the safe distance of a long shot, seeing Tyler near bathe himself in the viscous mass incites our own sense of disgust only indirectly. Yet a few seconds later the film dares us to come dangerously close ourselves, exposing us to an extreme close-up of a pot with a boiling, bubbling mass of fat that is part of the soap making procedure.

So how can we make sense of these rough, sticky, and plainly disgusting textures and substances, along with Tyler’s habit of provoking affective reactions by exposing Jack (as well as other people) to such discomforting, aversive, and even painful experiences?

Sara Ahmed argues that both “stickiness” and “disgust” have to do with corporeality, intensity and affect. Stickiness, according to her, can be thought of as “an effect of surfacing, as an effect of the histories of contact between bodies, objects, and signs.”[41] Likewise, disgust “operates as a contact zone; it is about how things come into contact with other things.”[42] More than that, “In disgust, contingency [defined in terms of the ‘contact’ between objects;’ my addition] itself is intensified; the contact between surfaces engenders an intensity of affect.”[43] While Ahmed’s concern is primarily the question of how something becomes to be perceived as disgusting through such contagious contacts, in Fight Club this process works the other way around: here, the function of disgust is that it creates a contact zone for Jack in a paradoxically productive manner. Reminding him of his own tactility, the sticky textures and transgressive bodily encounters create moments of embodied intensity that gradually bring him back to his senses.

We can relate such intensified tactility to the film’s corporeal hallmark experience – the fights – in similar manner. Ahmed describes how intensive collisions with another can stir an affect that not only lets us feel our own embodied existence, but also transforms our relationship to the world itself: “It is through such painful encounters between this body and other objects, including other bodies, that ‘surfaces’ are felt as ‘being there’ in the first place. To be more precise the impression of a surface is an effect of such intensification of feeling.”[44] This explains the productive function the fights have for Jack (as well as for the other men). They offer moments of intensification that bring him back to his bodily being and to the surfaces of the world.[45]

Conclusion

More than just visually marking different personalities and life style preferences, the textures and surfaces in Fight Club have an important affective function. Tyler not only corresponds with lacking aspects of Jack’s life by embodying the opposite: he also exposes Jack to new environments and new experiences, often pushing him – and us – out of his comfort zone. In doing so he reminds Jack of what it means to feel alive and inhabit the world with his whole bodily being. Moreover, the textures and surfaces in Fight Club play a key role in making tangible Jack’s tactile alienation from, and reconnection with the world through engaging our own sense of touch. Throughout the film there are indeed a number of sequences, similar to the haptic moment of the IKEA-sequence described earlier, that draw our attention to the film’s texture and surface itself. For example, the dreamy sex sequence of Marla and Tyler’s (Jack, really) first night, the montage sequence of Jack’s attempts at meditating the pain away when Tyler causes a chemical burn on his hand, and the jittering full frame of Tyler that (thanks to CGI) gets “stuck” in the projector, all work as such haptic moments. While the IKEA-sequence was primarily about Jack’s detachment, these other moments often signal intensified affective experiences that allow him to rediscover his embodied existence in the world. All of them, however, much like the sensuous assault of the opening sequence, intensify the cinematic experience of the viewer, the “cinesthetic subject [who] both touches and is touched by the screen.”[46] During these moments, the question of what is real in Fight Club fades into background. Instead, the question that matters is what feels real – not just for Jack but also for us.

Simin Nina Littschwager received her PhD in Film Studies from Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand) in 2015, where she currently also teaches in the Film Programme.

Notes

[1] Notably, he is referred to as Jack in the screenplay because of this habit, a convention that this essay follows from here on as well.

[2] Nancy Bauer, “The First Rule of Fight Club: On Plato, Descartes and Fight Club,” in: Fight Club, ed. Thomas E. Wartenberg (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2012), 126.

[3] Bauer, 123.

[4] Eva Laass, Broken Taboos, Subjective Truths: Forms and Functions of Unreliable Narration (Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2008), 150-165.

[5] George Wilson, “Transparency and Twist in Narrative Fiction Film,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 64.1 (2006), 81-95. See also: George Wilson and Sam Shpall, “Unraveling the Twists of Fight Club,” in: Fight Club, ed. Thomas E. Wartenberg (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2012), 78-111.

[6] Mack Hagood, “Unpacking a Punch: Transduction and the Sound of Combat Foley in Fight Club,” Cinema Journal, 53.4 (Summer 2014), 101.

[7] Hagood, 99.

[8] Hagood, 102.

[9] Vivian Sobchack, “What My Fingers Knew: The Cinesthetic Subject, or Vision in the Flesh,” in Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkely, CA: University of California Press, 2004), 67-71.

[10] Sobchack, 71.

[11] Hagood, 111.

[12] Smith 2009, as quoted in: Mark Ramey, Studying Fight Club (Leighton Buzzard: Auteur Publishing, 2012), 56.

[13] Rooney 1999, as quoted in Ramey, 58.

[14] Jennifer Barker, The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2009), 3.

[15] Barker, 25; emphasis in original.

[16] Barker, 25; emphasis in original.

[17] Lucy Fife Donaldson, “Moments of Texture: Introduction,” in Movie. A Journal of Film Criticism 6 (2015), 27. For a detailed exploration of this concept, see also: Lucy Fife Donaldson, Texture in Film (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

[18] Donaldson, 28.

[19] Donaldson, 27.

[20] Ian Garwood, The Sense of Film Narration (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), 14.

[21] Donaldson, 28.

[22] Donaldson, 27.

[23] Martine Beugnet, Cinema and Sensation: French Film and the Art of Transgression (Carbondale, Ill: Southern University Press, 2007), 19.

[24] Laura Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham, NC: Duke University Press,2000), 162-3, 176-7.

[25] Anthrin Steinke, “‘It’s called the Change-Over: The Movie Goes On and Nobody in the Audience Has Any Idea’: Filmische Irrwege und Unwahrheiten in David Fincher’s Fight Club,” in: Camera Doesn’t Lie: Spielarten Erzählerischer Unzuverlässigkeit im Film ed. Jörg Helbig (Trier: Wissenschaftllicher Verlag Trier, 2006), 149-51.

[26] Marks, 183.

[27] Steven Connor, “Sounding out Film,” 2000. http://www.stevenconnor.com/soundingout/

[28] Barker, 47.

[29] Barker, 81.

[30] Sobchack, 61.

[31] Sobchack, 78.

[32] Don Ihe, Listening and Voice: A Phenomenology of Sound (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1976), 45.

[33] Barker, 123; emphasis in original.

[34] It is also interesting to note in this context that both human heart rate and musical tempo can be referred to as pulse and can be measured in beats per minute (bpm), a value that is particularly important for electronic dance music such as Drum & Bass.

[35] Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club. With a New Afterword (London: Vintage Book, 1997 [96]), 21.

[36] Barker, 70.

[37] David Howes, “Hyperesthesia, or, The Sensual Logic of Late Capitalism,” in: Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader ed. David Howes (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2004), 288; emphasis in original.

[38] Barker, 60.

[39] Phil Powrie, “The Haptic Moment: Sparring with Paolo Conte in Ozon’s 5×5,” Paragraph 31.2 (2008), 208.

[40] Powrie, 210.

[41] Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 90; emphasis in original.

[42] Ahmed, 87.

[43] Ahmed, 89.

[44] Ahmed, 24; emphasis in original.

[45] Ahmed, 27.

[46] Sobchack, 71.