“Scenes from Parallel Lives”: Jacques Rivette and Marguerite Duras

Mary Wiles

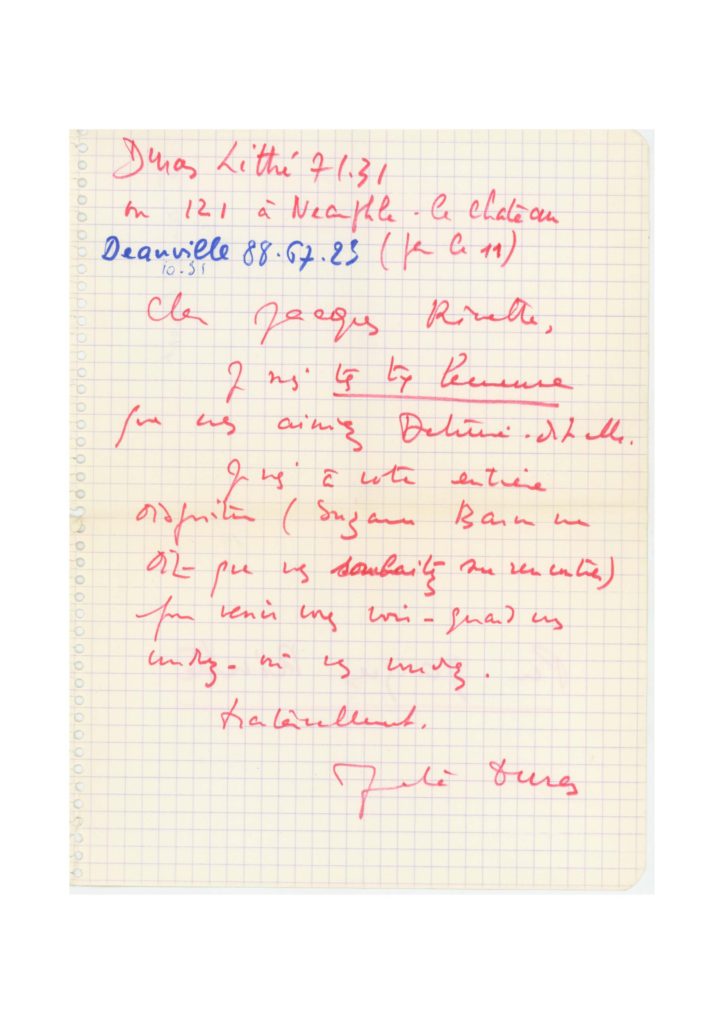

Shortly after the release of her first film, Détruire, dit-elle (Destroy, She Said; 1969), Marguerite Duras wrote a short note to Jacques Rivette, who had expressed his interest in meeting with her.1 She proposes a rendezvous:

Dear Jacques Rivette,

I am very, very happy that you liked Détruire dit-elle.

I am entirely at your disposal (Suzanne B. says that you would like to meet with me) to come and see you…whenever and wherever you like.

Fraternally,

Marguerite Duras

Almost a half century later, this piece of correspondence was discovered by chance amidst the clutter of dusty black-and-white photos, scripts, film canisters, and old letters, which Rivette had kept stashed away in the basement of the apartment on Rue Cassette that he and his wife Véronique had shared.

We can surmise that Rivette’s keen interest in meeting Duras was piqued by his desire to interview her for an upcoming issue of Cahiers du cinéma. In the immediate aftermath of May ’68, Rivette was understandably drawn to Duras, a fellow traveller whose film work, not unlike his own, would continue to evolve from within, drawing on the auteurist themes of erotic obsession, madness, and loss that had informed her fiction. In November 1969, Rivette in collaboration with Jean Narboni conducted the seminal interview “Destruction and Language” (La destruction de la parole), in which the author discusses her auto-adaptation of novel to film, Détruire, dit-elle. Rivette begins with this observation, “…it seems you [Duras] want more and more to give successive forms to each of the things—let’s not use the word stories—that you write…” (…c’est le fait qu’il semble que, de plus en plus, vous avez envie de donner des formes successives à chacune des—non pas des histoires, que vous écrivez…), and follows up by pointing to the stage directions, “Note for Performance,” which are included as an addendum to her identically titled novel.2

Like Duras, Rivette had approached his own first feature-length adaptation, Suzanne Simonin, la religieuse de Denis Diderot (1966), through theatre. In 1963, he had made his theatrical debut directing Jean Gruault’s adaptation of La religieuse at Studio des Champs-Élysées. Theatre was indispensable to the artistic evolution of Rivette and Duras in the 1960s, when the two directors worked side by side towards the genesis of distinctive visions of cinematic mise en scène, which would be founded equally upon the destruction of traditional generic boundaries between “texte théâtre film.”

Cycles: Duras and Rivette

The different dimensions of theatricality, which coexist in the films of Duras and Rivette, take shape within the respective cycles that define the evolution of their work throughout the 1970s. Comprised of three novels and three films written and directed by Duras between 1964 and 1976, the Indian cycle began with the novel, Le ravissement de Lol V. Stein, and culminated in the mid-1970s with the release of the penultimate film in the cycle, India Song (1975).3 Like Détruit dit-elle, India Song had initially been conceived as a stage production. The theatrical scenario, which had been commissioned in 1972 by Peter Hall for the National Theatre of London, was published in 1973 with the subtitle “texte théâtre film.” The title not only signals the shift between genres and mediums but also, according to Duras scholar Michelle Royer, can be understood as the author’s attempt “…to capture the movement of rewriting with its erasures, amendments, and reformulations.” (…de saisir un mouvement, le mouvement de réécriture avec ses gommages, ses ratures, ses reformulations.)4 The most mutable of Duras’s works in the cycle, India Song: texte théâtre film, was later recorded for French radio, and then released as a film in 1975, whose fully intact sound track was subsequently recycled over a different image track in the companion film, Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta désert (1976). In the latter film, the ornate palace that had been the site of the story of India Song is shown in ruins, emptied of characters and objects. In these paired films, Duras uses uncanny duplications (doubled soundtracks, doubled narrators, doubled topographical spaces and scripts), recalling the reduplication of the medium accomplished several years earlier by Rivette in the eight-part, nearly thirteen-hour Out 1: Noli me tangere (Out 1: Touch Me Not; 1970-71) and the re-edited four-hour version, Out 1: Spectre (1974). In the latter film, Rivette selects and reorganizes the images from the long version but also adds sound at certain moments to achieve a machine-like “meaningless frequency.”5 Could Rivette’s radical experimentation with serial form and sound at the beginning of the decade have influenced Duras’s own distinctive formulation of her film cycle?

In some sense, Rivette’s Nervalian cycle of films, Les filles du feu, can be viewed as a supplement to the unfinished serial, Out 1, 2, 3…. Without doubt, the cycle, which Rivette later renamed Scènes de la vie parallèle, represented the culmination of his dream of an around-the-clock cinema showing continuous programs.6 Each of the four films in the cycle was to have represented a different genre—a love story, a film of the fantastic, a western, a musical comedy—and Rivette confirms that certain elements and themes were to circulate from one story to another, and that certain characters were to reappear from film to film in different guises, playing major roles in one story and minor roles in another.7 All four films were to take place within a partially invented mythological framework corresponding to the forty days of the traditional carnival cycle, a period that includes three lunar phases when rival goddesses of the moon and sun come to earth and mingle with mortals. Unfortunately, the four films that Rivette envisioned were never completed; however, he did finish filming the fantastic thriller Duelle (Duel; 1976) (Scènes de la vie parallèle: 2). Une quarantaine and Noroît (Northwest Wind; 1976) (Scènes de la vie parallèle: 3). Une vengeance), which were to serve as the second and third parts, respectively, of the four-part film cycle.

Sound and Cycles

Close collaboration with their mutual producer Stéphane Tchalgadjieff allowed Rivette and Duras the freedom to develop their radically experimental approach to sound in film. Rivette conceived of uniting Les filles du feu through “…a progression of complication linked to the intervention of music on action” (…une progression de complications, liée à l’intervention de la musique sur l’action.)8 The cycle would adhere to Rivette’s strict conception of direct sound practice, which demanded that musicians be present on the set and improvise freely, while the camera recorded them alongside the actors. Rivette maintained: “There was not a moment, not for the piano of Wiener (Duelle) nor for the three musicians (Noroît), even when they do not appear in the image, that would be altered later in the sound mix.” (Il n’y a pas un moment, tant du piano de Wiener, que les trois musiciens, même quand ils ne sont pas du tout dans l’image, il n’y a pas un moment qui soit repris ensuite au mixage.)9 He envisaged a progressive expansion in the role of music from film to film, and reflected later that he had conceived of the fourth and final film as a musical comedy extravaganza with orchestral accompaniment modeled on Jean Renoir’s Le carosse d’or (The Golden Coach; 1952).10 If Rivette intended to enmesh music and image by recording them on the set simultaneously, Duras would accomplish a radical split between the sound track and the image track in the Indian cycle. At the commencement of the cycle, Duras refers to the separation between the soundtrack and the image track in La femme du Gange as constituting two distinct films, “the film of the images and the film of the voices” (le film de l’image et le film des voix).11 Not unlike the escalating aural trajectory Rivette had envisioned for Les filles du feu, the soundtrack in the Indian cycle films takes on increasing importance; however, its visual narrative betrays what Madeleine Borgomano describes in L’écriture filmique de Marguerite Duras as the “progressive stripping down” (dépouillement progressif) that culminates in the evacuation of story content from the image within the final film, Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta désert.12

Conceptualized as a midway point in their respective cycles, India Song and Duelle represent an important transitional moment in their evolution: both films embrace the elevated role of musical ritual, poetic incantation, and dance movement, revolutionizing cinematic sound practice; both films offer a unique iteration of a central drama that is repeated and altered between texts in their respective cycles, and both films present the audience with a phantasmatic world in which phantom doubles move through geographical locales that are transformed into mythic, magical spaces—from an illustrious French embassy to an abandoned tennis court in India Song, from a modern dance studio to a deserted park at dawn in Duelle.

Goddesses and Divas

The works of the Indian cycle and those of Les filles du feu are composed of a constellation of characters that revolve around their dual heroines. Goddess of the Sun Viva (Bulle Ogier) and Goddess of the Moon Leni (Juliet Berto) are introduced in Duelle where each one reigns over a solar or lunar landscape, respectively.13

The two occupy a magical temporal zone, une quarantaine (forty-day period) as they search for an enchanted jewel that will enable them to remain on the earth. Duras’s heroines are introduced in the novel, Le ravissement de Lol V. Stein (1964), which engenders the Indian cycle and serves as its backstory. The passionate obsession and madness of Lola Valérie Stein originate at a ball in T. Beach where she looks on as her fiancé Michael Richardson is spirited away by a mesmeric woman, whose name is later revealed to be Anne-Marie Stretter. As Duras scholar Deborah N. Glassman observes in her seminal study, Marguerite Duras: Fascinating Vision and Narrative Cure, the ball becomes “a vanishing point” of all the Indian cycle novels and films, a “bewitching event that remains extrinsic to the narrative frames seeking to capture it.”14 Lol remains an absent presence in India Song, whose double in the region of S. Tahla, Anne-Marie Stretter, is placed on display as she dances at the reception held in 1937 at the French embassy in Calcutta. Both Anne-Marie Stretter and Lol are phantom figures, resurrected from an arcane past, and in this way, resemble Rivette’s sun and moon goddesses whose perambulations through Paris are determined by their transitory status as exiles from an invisible realm of the dead.

In both films, female characters, in particular, are drawn from the past yet become embodiments of the present.15 Rivette’s long-time co-scenarist Pascale Bonitzer elaborates on the nostalgic mode of address of India Song, locating the source of the film’s nostalgia not only in its visual and aural sign system designed to conjure up an exotic terrestrial paradise, but also in its evocative presentation of the caste of colonial grande bourgeoisie, the “beautiful and racist” (beau et raciste) cadre, fittingly fated to disappear.16 He concludes by arguing convincingly that Duras adopts and transforms the retro drama, exceeding its tragic, historical dimensions and pushing it towards the extremes of parody and caricature. The repeated use of very long takes and in-depth staging, the sacerdotal performance style, and above all, the radically disjunctive soundtrack, Bonitzer maintains, imbue the “so-called” tragic love story of Stretter and Richardson with insidious comic undertones.17 What he terms “a supplementary screen of the past” (l’écran du passé), which insinuates itself into the breach between the silent images and the off-screen music and voices coming from an undefined space, provides the spectator with a source of covert fascination, made possible by the fact that the bodies and faces that appear like ghosts never express themselves with “living voices” (de vive voix).18 Duras reconfigures the retro drama in India Song, drawing on the performance tradition associated with silent cinema to achieve a singular mode of non-narrative filmmaking.

Could “the powerful visual fascination” that the character Anne-Marie Stretter wields be attributable, in part, to the performance tradition associated with a silent film genre, in particular with that of the diva film?19 Film historians Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs attribute the emergence of the diva in the 1910s to the European film acting tradition, which was comprised of lengthy takes and staging in depth, giving the actress the time and space to develop her performance style.20 The diva performance tradition was pioneered by the Italian actress Lyda Borelli, whose inaugural film role in Mario Caserini’s diva film Ma l’Amor Mio non Muore! (Love Everlasting; 1913) remains the prototype of the genre.21

Brewster and Jacobs affirm that diva films were reliant on the centrality of the diva and thus, created “scenes in which the diva is left alone to express her reaction to the big situations—a way of directing attention to the star’s performance.” 22

Figure 5. Stretter (Delphine Seyrig), “imprisoned by a sort of suffering” (prisonnière d’une sorte de souffrance)

Such “star turns” reoccur in India Song, such as the scene at the reception at the French embassy in which the inimitable Delphine Seyrig in the role of Stretter slowly pauses, then poses before the wall mirror, and finally turns and exits; on the soundtrack, an off-screen male voice reflects, “She seemed imprisoned by a sort of suffering.” (On la dirait prisonnière d’une sorte de souffrance.) Seyrig’s performance closely conforms to the persona of the mater dolorosa (sorrowful mother), which film historian Angela Dalle Vacche associates with the acting style of the diva, observing, “…the diva is mostly a woman who suffers because she was born a woman, whether she has children or not.” 23 An even more powerful moment in this respect is the scene in which Stretter reappears in the identical space, this time present only as a sombre mirror reflection, left alone to contemplate the traumatic and disturbing encounter in the previous scene with the vice-consul from Lahore (Michael Lonsdale), whose screams continue to reverberate through the cavernous space of the French embassy

Seyrig, whose long-suffering character Stretter embodies the silent dignity and balletic elegance of the prima donna, adopts and transforms the performance style of the diva in India Song. Trained in the theatre, Seyrig shaped the diva role to suit the dimensions of her character, reequipping it with the restrained, minimalist acting style associated with the naturalist dramaturgy of Henrik Ibsen. Seyrig knew Ibsen’s work well. Indeed, it was her performance in Ibsen’s play, An Enemy of the People, in New York that caught the attention of director Alain Resnais, who would subsequently recruit her for L’année dernière à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad; 1961).24 It could be that Seyrig’s studied theatrical performance style had been modelled on that of Italian actress Eleonora Duse—the great rival of Sarah Bernhardt—whose “non-melodramatic” performances of Ibsen, according to Brewster and Jacobs, were the subject of legend.25 The naturalist acting style that Seyrig had cultivated in both theatre and film productions lends credence to her interpretation of the character Stretter, for as Brewster and Jacobs point out, “Ibsen’s plays…placed a great deal of weight on the idea of repression—the inability of characters to express themselves or even to understand the situation in which they found themselves.”26 Duras’s imposition of a recorded soundtrack on the unfolding silent spectacle of India Song effectively completes Seyrig’s opaque performance. Moreover, the entire cast of characters also appears entranced, as Duras scholars have routinely observed, due to their preoccupation with the sound of their own recorded voices that are being played back while they are being filmed.27 Beyond vocal echoing, Duras also resorted to the reduplication of the image and in doing so, recasts the pictorial style of silent film acting. Mirrors that played a prominent role in diva films where they served to multiply and center the diva’s expressive gestures are omnipresent in India Song; Stetter and her entourage appear and disappear by turns in the mirrored reflected spaces that at times become indistinguishable from the fictional space of the film.28 In her use of disjunctive sound and mirrored space, Duras reshapes the diva persona, which had evolved as part of the pictorial acting style of the 1910s.

Rivette was also undeniably drawn to the theatrical world of the diva. Prior to conceptualizing Scènes de la vie parallèle, he had envisioned a film entitled Phénix that was to have focused on a reclusive actress who lived in a grand Paris theatre, a role intended for Jeanne Moreau. In his discussion of the film with Hélène Frappat, Rivette recalls: “Phénix came after Out… I had this idea of Sarah Bernhardt meeting the Phantom of the Opera, and immediately I thought of Jeanne Moreau.” (Phénix est venu après Out… j’ai eu cette idée de Sarah Bernhardt rencontrant Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, et aussitôt j’ai pensé à Jeanne Moreau.)29 In collaboration with Eduardo de Gregorio and Suzanne Schiffmann, Rivette drafted the scenario for Phénix, setting forth the story set in the late nineteenth century of a diva named Deborah who he described as “an actress, famous, venerated, and already even a bit mythical, in the image of those legends of the theatre, which for us are evoked by the names Sarah Bernhardt or Eleonora Duse.” (actrice, célebrée, prestigieuse, et déjà même un peu légendaire, à l’image de ces ‘monstres sacrés’ qu’évoquent, pour nous, les noms de Sarah Bernhardt ou Eleonora Duse.)30 Rivette was never able to acquire the funding he required to proceed with his diva film; however, certain qualities of Rivette’s phantom goddesses in Duelle recall those of the diva, who in her finest moments, according to Dalle Vacche, involves “a certain kind of ineffable spirituality, a ritualistic otherness, and an intuitive aura about invisible things.” 31 Sun and moon goddesses in Duelle borrow the diva’s imperious, aristocratic demeanour, her whimsical and at times extravagant dress style, and her superfluous costume changes.

Taxi-Girls and Divas at the Dance Hall

Rivette’s goddesses take center stage at “Le Rhumba,” a Paris dance club whose mirrored, labyrinthine decor does not simply invoke that of the diva film, but also the numinous landscape of Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (Orpheus; 1950) where the messenger of death Heurtebise confides the deepest of secrets: “Mirrors are the doors through which death comes and goes” (Les miroirs sont les portes par lesquelles la mort vient et va). Cocteau’s stylistic legacy is everywhere apparent in Duelle, which takes its inspiration directly from his three-act play, Les chevaliers de la table ronde (The Knights of the Round Table; 1937). The parallel realities of Duelle recall those of Cocteau’s play in which human and supernatural forces struggle for dominance in King Arthur’s court whose members are possessed by evil doubles governed by the magician Merlin. While drawing on Cocteau’s sense of myth and magic, Rivette models his dance club on the New York taxi-dance hall, which became popular after the First World War.32 He hand-picked the ageing piano player Jean Wiener, who appears alongside actors on the set. It was Cocteau who had first noticed Wiener in 1921 at a small bar called the Gaya, where he marvelled at the pianist’s ability to play American music “marvellously.”33 It is unsurprising that Rivette would recruit Wiener for his own club where the pianist, who is occasionally accompanied by a backup band, improvises during the filming, recalling the era of silent film when live music accompanied the screening. Leni and Viva who both frequent Le Rhumba confer with and compete against their respective mortal counterparts, Lucie (Hermine Karagheuz), who mans the front desk of a nearby hotel, and Jeanne/Elsa (Nicole Garcia), who works at the dance club as a taxi-girl.

The performance style of mortals Lucie and Jeanne/Elsa is designed to counter that of the diva tradition, for it is shaped to suit the working-class milieu of the taxi-dance hall and the taxi-girls who worked there. The acting style of Hermine Karagheuz in the role of Lucie is presented as spontaneous and unrestrained. She sports a red club jacket for much of the film, which marks her as a mortal, for it provides a conspicuous contrast to the flowing capes, glistening gowns, and iridescent tailored jackets worn by the goddesses. Opposed to these svelte, poised figures, Lucie responds to her environment with sudden, fitful movements, darting here and there with an animal impulsivity that Rivette will push to an extreme in Merry-Go-Round (1977-1978; released 1983).

Wrapped in a double-breasted trench coat that might have come from the set of Kiss Me Deadly (dir. Aldrich; 1955), Nicole Garcia provides a demure and desultory performance well suited to her character Jeanne/Elsa’s status as a taxi-girl, which is signalled by her double name.

Rivette was familiar with New York popular culture of the 1920s, particularly the music, song and dance subculture from which the taxi-girl emerged. The director’s initial interest in the taxi-girl may have been piqued by Barbara Stanwyck’s suggestive performance as a jaded taxi-girl in pre-code classic, Ten Cents a Dance (dir. Lionel Barrymore; 1931), which was inspired by Lorenz Hart’s and Richard Rogers’s popular song of the same name that is played over the title sequence.

Or perhaps Rivette first encountered the taxi-girl in the work of expatriate writer Henry Miller, for whom she had served in Tropic of Capricorn (1939) as a symbol, a mythic creature who represented the alluring and seductive side of the American dream.34 The taxi-dance hall that had inspired music, film, and fiction was typically located in urban areas of mobility, such as tenement districts where small apartments, furnished rooms, and inexpensive residential hotels predominated.35 These places of amusement were tinged with an element of social danger, partly because of the inevitable commingling of classes and ethnicities in less expensive venues. In his sociological study of the urban dance hall, Paul G. Cressey points out that the taxi-dance hall provided a means of escape during the inter-war years from oppressive restrictions, enabling its clientele and taxi-girls alike to project themselves into alternative theatrical roles.36 Each dancer would typically adopt a “professional” name that was suggestive of her new self-conception: Alma Heisler to Helene de Valle, Eleanor Hedman to Gloria Garden, Alice Borden to Wanda Wang and Mary Maranowski to Jean Jouette.37 Garcia indulges in the theatrical role-playing of a taxi-girl in the scene in which she shamefacedly confesses to the inquisitive Viva that she works in a dance club under the assumed name of “Elsa” because she found her real name “Jeanne” “common” (vulgaire).

Theatrical role-playing that was part of the performance subculture of the taxi-dance hall in the 1920s extended beyond aspirational social class roles to include taboo homoerotic fantasies. Taxi-girls were known to “frolic together over the floor” when business was slow, according to Cressey, soliciting the pleasurable gaze of side-line spectators.38 Rivette reimagines the gender dynamics of the taxi-dancers’ performance, tailoring the theme of lesbianism to suit the cultural context of his Pigalle dance club. Moon goddess Leni disguises herself not only as a mortal but also a male patron when she appears at Le Rhumba in drag, dressed in a glossy red dinner jacket, black trousers, and tie with her dark hair pulled back in a tight bun. She ostentatiously presents her dance ticket to taxi-girl Elsa, who obliges, slipping the ticket inside her black lace décolletage.

Their careful performance conforms closely to the protocol of the actual taxi-dance hall where each dancer would guard her tickets closely until the end of the night when she would redeem them from the management for a nickel each. Yet Juliet Berto’s exaggerated performance of social gallantry on the dance floor, which includes twirling her wrist decorously before taking her dance partner’s hand, can be seen as a parodic commentary on the model of masculine entitlement that is embodied in the fictional prototype of the moneyed male dance hall patron—the grotesque patriarch Lord Christie, whom we never see but whom Elsa describes as a big-time spender able to buy up all the evening’s tickets. As the dance scene unfolds, the profilmic spectator looks on from the sideline, amused and pleasurably enmeshed in the pervasive ambiance of sexual ambiguity cultivated in the club.

The Dance and Homoerotic Interludes

The playful flirtation between the duplicitous moon goddess Leni and her unsuspecting dance partner Elsa culminates in a homoerotic interlude during their subsequent rendezvous at an empty dance studio. From the outset of the scene, the goddess’s statuesque pose and resolute gaze ahead command respect. The sharp, strident linearity of her tailored ensemble is offset by the flowing curves of her dark blue cape billowing in an unearthly wind. Her costuming, like her comportment, could be compared to that of the bohemian dandy whom Albert Camus describes in L’homme révolté: “The dandy creates his own unity through aesthetic means…. ‘To live and die in front of a mirror’ such was, according to Baudelaire, the watchword of the dandy.” (Le dandy crée sa propre unité par des moyens esthétiques…. ‘Vivre et mourir devant un miroir’ telle était, selon Baudelaire, la devise du dandy.)39

Leni’s authoritative march across the studio to greet Elsa is at odds with the gentility of her gestures; she delicately removes Elsa’s sunglasses and asks whether she has been crying. As Elsa discloses her confusion and malaise, Leni shadows her hesitant movements across the studio floor. Rivette’s choice of deep focus ensures that Wiener and his piano remain in view, while his music marks their steps in time as would a metronome. Moon goddess and mortal, brunette and blonde, pose against the horizontal ballet barres, like students waiting for dance class to commence. Their doubled reflections, which haunt the mirrored space of the studio, disappear when Leni at last leans over and kisses Elsa full on the mouth.

The tender moment invokes the celebrated sapphic kiss in Josef von Sternberg’s Morocco (1930). As James Naremore points out in his analysis of Marlene Dietrich’s performance in Acting in the Cinema, her relationship to women is eroticized in this sequence, yet due to the introduction of fetishistic strategies, Sternberg and Dietrich are able “to preserve the boy-meets-girl plot required by Hollywood narrative.”40 Whereas Dietrich’s sexual destiny in Morocco is ultimately bound to the heterosexual romance, Leni’s is untethered from the conventional expectations of classical Hollywood cinema. From within the parallel universe that Rivette proposes in Duelle, the goddesses are free to engage in potentially transgressive, homoerotic theatrical role-playing, challenging the audience to envision an alternative world, or parallel universe, where sexual desire can take multiple forms.

A 180-degree cut marks the radical shift from the slow, sensual tenor of the scene, which has been sustained, in part, by Wiener’s musical improvisation. Leni transitions into a seemingly effortless solo performance in which she compares her own graceful dance moves across the studio floor to the seductive moves of her supernatural adversary Viva, who, she feels, is playing the part of the manipulative seductress by stealing the man with whom Elsa has been in love. As Leni spins and prances across the studio dance floor, mimicking Viva’s femme fatale persona, Wiener shifts to the lilting musical motif previously associated with the sun goddess and her seduction of the mortal Pierrot, a role designed for the talents of dancer Jean Babilée who had performed decades earlier in Cocteau’s ballet, Le jeune homme et la mort (The Young Man and Death; 1946).

Leni’s lines, which are spoken in synchrony with her dance steps, and the accompanying piano refrain evoke the heterosexual romance of Viva and Pierrot, yet the profilmic spectator is simultaneously invited to identify with Elsa’s eroticized gaze whose object in the scene is Leni. The overlapping of homosexual and heterosexual desire within this scene—the final dance scene in the film—recalls similar Durassian strategies, which Renate Günther discusses in her exhaustive analysis of gender and sexuality in the director’s films.41

Lesbian desire is never visually represented on the screen in India Song; it is instead aurally articulated by two disembodied female voices whose narration of the love affair of Stretter and Michael Richardson (Claude Mann) unfolding before them overlaps and at certain moments blends with their own. For Günther, this “blending of sexualities” is clearly expressed in the inaugural dance scene in the film.42 Carlos d’Alessio’s title song introduces the scene in which the lateral, gliding movement of the camera finally comes to rest on the dancing couple who appear before us in a mirror reflection, as they are simultaneously being observed by a blond male guest, the double of Richardson.

The two off-screen female voices speak about the passion of the heterosexual couple Stretter and Richardson and simultaneously about their own homosexual passion. Voice 1 poses the question, “Why are you crying?” to which Voice 2 replies, “I love you so much I can’t see any more, can’t hear, can’t live.” (Sur quoi pleurez-vous? Je vous aime jusqu’à ne plus voir, ne plus entendre, mourir.) Voice 2’s double role as off-screen lesbian interlocutor and emotionally implicated onlooker of the on-screen heterosexual romance recalls that of Elsa, whose response to Leni’s eroticized approach in the dance studio could be interpreted as that of the desirous lesbian lover or the entranced observer implicated in the off-screen affair of the heterosexual couple Viva and Pierrot.

The correspondences and uncanny echoes between the first and the last dance scenes in India Song and Duelle, respectively, can be attributed, in part, to the directors’ mutual interest in the interplay of sound and image: the mirrored space of the dance of seduction in each film is both complemented and counterpoised by the musicality of the piano music and the female voice (off-screen in Duras, on-screen in Rivette).

Conclusion

Maurice Darmon’s observation that India Song is “a film about the end of a world” (un film sur la fin d’un monde) is also true of Duelle.43 At the close of the film, both mortal and moon goddess seek deliverance as they vanish from the twilight world of the quarantaine into darkness beneath the roar of the metro. The disappearance of diurnal and nocturnal goddesses into a mysterious void at the end of Duelle invokes that of the evanescent Stretter whose suicide is disclosed at last by a hushed female voice, as Duras’s camera lingers on a dark, occluded horizon—an empty space at dawn. The two films leave us with the disquieting sense of what Jacques Aumont has identified in the work of Rivette and Alain Resnais as “oblivion as it is occurring, even if it is a partial forgetting, light, allusive…” (l’oubli en train d’advenir, même si c’est un oubli partiel, léger, allusif,…).44 In their respective cycle films, Duras and Rivette seem concerned not simply with the mythic past and archetypal figures that supersede history but with passage, or to use Aumont’s phraseology, “le passage du passé” (the passage of the past).45 Duelle ends abruptly with a Rivettian phantasmic moment, a sudden cut to black that posits the eradication of time, the unimaginable passage into a parallel universe that is set in motion by the mortal Lucie’s recitation of the magician Merlin’s demented spell from Les chevaliers: “Two plus two no longer equal four/all the walls can fall away” (Deux et deux ne font plus quatre/tous les murs peuvent s’abbatre).

India Song closes with the unintelligible chanting of the mad beggarwoman from Savannakhet, Laos, whom we never see but whose passage is shown in the camera’s movement across a map of Indochina, as names of potential destinations float past us mapping an historical cartography of exclusion. In the end, the mortal Lucie and the nameless madwoman might be understood to be the “apocalyptic agents,” which Leslie Hill associates in the 1960s and 1970s work of Duras with “… this task of radical destruction or transformation” that produces hope for “a new beginning arising out of the ashes and destruction of the past.”46 For Duras and Rivette, this ritual of auto-destruction and regeneration is evidenced in their mutual desire to cull from the remains of the previous work(s) in the creation of the next within their respective film cycles.

By the mid-1970s at around the time that Duelle and India Song were in production, Rivette and Duras had both consolidated their reputations as mavericks within the respective domains of film and literature from which they had emerged in the 1950s. As filmmakers, they were united in their mutual desire to conceive of a new relationship between the soundtrack and the image, to discover a new approach to acting that would involve musical space, and to achieve a radical transformation of the male-focused system of representation of mainstream cinema. Their films from this period were interconnected not only through their relationship to experimental and cyclical form but also through other diverse associations, such as the resonance of the female voice onscreen and off, the representation of the female body in dance and performance, and the evocation of desire between women. The filmic imaginations of Rivette and Duras were closely allied, particularly in the manner in which they chose to portray women’s lives in their respective cycles.

At the close of the decade, both directors’ work underwent a radical shift in direction.47 Duras decided to end her filmmaking career and return to writing, her “native land” (au pays natal).48 Rivette relinquished his dream of an around-the-clock serial cinema, abandoning his work on the mythological cycle of Les filles du feu. He would finally return to the tetralogy decades later with the haunting love story, Histoire de Marie et Julien (2003), a retooling of the original project, Marie et Julien (1975), which was to have been the first film in the cycle. In a 1990 filmed interview, Rivette expressed regret at not having been able to make this film that he had planned in collaboration with his actors Leslie Caron and Albert Finney, who, he felt, had displayed a powerful synergy on the screen.49 His sudden disappearance from the set in the summer of 1975 after only three days of filming had prompted Duras to offer to step in and complete the film. At that moment, Duras may rightly have seen herself as the director most attuned to Rivette’s work and able to assist him, but the collaboration was not to be. Rivette’s team of actors remained steadfast in their refusal to proceed without him. We can only wonder at the direction this phantom cycle film might have taken, had it been directed by both Rivette and Duras, and the extent to which such a hybrid project would have affected their respective film cycles and careers in the years that followed.

After a brief hiatus from filmmaking brought on by exhaustion, Rivette returned once more to the pleasures and terrors of the contemporary Paris cityscape in Le Pont du Nord (1982), familiar terrain that he might well have described in Durassian terms as his “native land.” The film’s release prompted the final official rendezvous between the two filmmakers, yet the tables were turned, for this time it was Rivette’s new film that was the impetus for their conversation. Duras delighted in speaking with him about it:

I see it [your film] in Paris, in a Paris that is timeless, unpredictable, undreamt-of, as a city that was admirable and that is in the throes of destruction and that within this destruction, there are two errant women… we have never seen women like this out in the open air, without any attachment, without identity, a film that runs along like a river, admirable, admirable, admirable.

(Je le vois dans Paris, dans Paris hors du temps, imprévisible, incroyable, comme une ville qui a été admirable et qui est en cours de destruction et que dedans cette destruction, il y a ces deux femmes errantes… on n’a jamais vu de femmes comme ça dans l’air libre, sans attache aucune, sans identité, film qui est comme coule une rivière, admirable, admirable, admirable.)50

It was, perhaps, in its capacity to present unusual, unforgettable portraits of women that Duras found Rivette’s work so vital and also closest to her own. In the final instance, there can be no doubt that the evolving rapport between Rivette and Duras was founded upon a deep “fraternal” understanding and complicity.

Mary Wiles is Senior Lecturer in Cinema Studies at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand. She is the author of Jacques Rivette (University of Illinois Press, 2012) and has published on contemporary French and New Zealand cinemas in such journals as Senses of Cinema, Illusions, Australian Journal of French Studies, and Studies in French Cinema. She has also been interviewed in the second issue of The Cine-Files, where she discusses her rendezvous with Jacques Rivette.

Notes

- Duras co-directed La Musica (1966) with Paul Seban, which featured Delphine Seyrig and Robert Hossein; Détruire, dit-elle is the first film for which she claimed sole directorial credit.

- Jacques Rivette and Jean Narboni, “An Interview with Marguerite Duras” in Destroy, She Said, Marguerite Duras, trans. Helen Lane Cumberford (New York: Grove Press, 1970), 91. Rpt. of “La destruction de la parole: entretien avec Marguerite Duras par Jean Narboni et Jacques Rivette,” Cahiers du cinéma, 217 (November 1969): 45-57, (p. 45). It may have been Michael Lonsdale’s performance as the character Stein in Détruit, dit-elle that inspired Rivette to cast him in his next film Out 1: Noli me tangere in the role of theatre director Thomas.

- Deborah N. Glassman, Marguerite Duras: Fascinating Vision and Narrative Cure (London: Associated University Presses, 1991), 16, 34. Duras scholars generally concur with Glassman who advises that India Song has its origins in the literary texts Le ravissement de Lol V. Stein (1964), Le vice-consul (1965), and L’amour (1971). In a cinematic context it is related to La femme du Gange (1973) and Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta désert (1976).

- Michelle Royer, L’écran de la passion: Une étude du cinéma de Marguerite Duras (Mount Nebo: Boombana Publications, 1997), 23.

- Jonathan Rosenbaum, Lauren Sedofsky, and Gilbert Adair, “Phantom Interviewers Over Rivette,” Film Comment (September-October 1974): 18-24, (p. 23).

- Scènes de la vie parallèle (Scenes from a Parallel Life) is the official title submitted to the C.N.C (Centre national de la cinématographie) of the 1970s cycle of films that Rivette had envisioned, which is also known as Les filles du feu. Duelle (1976) and Noroît (1976) serve as the second and third parts, respectively, of the four-part film cycle that was never completed. Histoire de Marie et Julien (2003) is a retooling of this old project from the 1970s.

- Serge Daney and Jean Narboni, “Entretien avec Jacques Rivette,” Cahiers du cinéma 323-24 (May-June 1981): 43-49, (p. 48).

- Ibid., 48.

- Serge Daney and Jean Narboni, “Entretien avec Jacques Rivette,” Cahiers du cinéma 327 (September 1981): 8-21, (p. 18).

- Jacques Rivette, “Scenes from a Parallel Life: Jacques Rivette Remembers (2),” interview by Wilfried Reichart, conducted for WDR programme: Jacques Rivette and the Parallel Life, 2004. In The Jacques Rivette Collection. DVD Box Edition. Arrow Academy, 2016.

- Marguerite Duras, Nathalie Granger suivi de La Femme du Gange (Paris: Gallimard, 1972), 103.

- Madeleine Borgomano, L’écriture filmique de Marguerite Duras (Paris: Éditions Albatros, 1985), 11.

- Bulle Ogier also performed in Duras’s films, Des journées entières dans les arbres (1976), Le navire Night (1979) and Agatha et les lectures illimitées (1981).

- Glassman, 34.

- See Maurice Darmon, Le cinéma de Marguerite Duras: La Trilogie Anne-Marie Stretter Tome 2: 1974-1976 (Paris: 202 Éditions, 2015) who stresses the convergence of the past and the present in India Song. Darmon observes: “That beggarwoman, that ‘loony with red hair’, the color of the devil, the color of exclusion, of treachery and the mane of Judas, it is me Duras, and Calcutta is here, at the heart of Europe, exterminated by all of the fascisms…” (Cette mendiante, cette ‘dingue aux cheveux rouges’, couleur du diable, couleur de l’exclusion, de la traitrise et chevelure de Judas, c’est moi Duras, et Calcutta c’est bien ici, l’Europe au cœur, exterminée par tous les fascismes…), 41.

- Pascale Bonitzer, Le Regard et la voix (Paris: Union Générale d’Editions, 1976), 148. Bonitzer observes: “The music, the fragrance, the dreams, which these names evoke, and the date, 1937. But this charm, what is it really?… Of course, it’s obvious: the retro mode! Retro, which is to say nostalgic.” (La musique, le parfum, le rêve dont ces noms sont chargés, et la date, 1937. Voyons, mais ce charme, quel est-il? …Mais oui, bien sûr, cela crève les yeux: la mode rétro! Rétro veut dire nostalgique.) Bonitzer began as Rivette’s co-scenarist during the production of L’amour par terre (1984) and continued in that capacity on every film thereafter.

- Bonitzer, 150, 151.

- Bonitzer, 150. In the course of his discussion, Bonitzer compares the characters of India Song to those of Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau (1974). He observes: “Even more than in Céline and Julie, one thinks of Casares’s The Invention of Morel: these [bodies and faces] are the dead, phantoms, traces, without any more consistency than phosphene, which glide past us.” (Bien plus que dans Céline et Julie, on pense à l’Invention de Morel (Casares; 1940): ce sont des morts, des fantômes, des traces, sans autre consistance que des phosphènes, qui glissent ainsi devant nous…), 150.

- Glassman, 81. Glassman associates the representation of Stretter with the classical era of Hollywood cinema, observing, “…the languorous and sole feminine center of male attention is treated like a Hollywood star, the cast is dressed in evening wear of the late 1930s,” 76.

- Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 111-112.

- Angela Dalle Vacche, Diva: Defiance and Passion in Early Italian Cinema (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008), 180.

- Brewster and Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema, 112.

- Dalle Vacche, Diva, 7.

- For a detailed discussion of the influence of Ibsen on Alain Resnais, see T. Jefferson Kline’s “Last Year at Marienbad: High Modern and Postmodern,” in Masterpieces of Modernist Cinema, ed. Ted Perry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006), 208-235.

- Brewster and Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema, 95.

- Ibid.

- For a detailed discussion of the interrelation of sound and image in India Song, see Glassman, who takes issue with the disjunctive status of sound in India Song in “On and Off: Sounds and Images,” Marguerite Duras, 73-76; also see Renate Günther, “Words and Images: Filming Desire,” Marguerite Duras French Film Directors Ser. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 23-61; see also Dong Liang, “Marguerite Duras’s Aural World: A Study of the Mise en son of India Song,” In the Dark Room: Marguerite Duras and the Cinema, eds. Rosanna Maule with Julie Beaulieu, New Studies in European Cinema 7 (Bern: Peter Lang, 2009): 211-234.

- Silents Please! “Fatal Passions: An Overview of the Italian Divas.” Accessed 22 April, 2017. https://silentsplease.wordpress.com/2014/12/10/ma-lamor-mio-non-muore/

- Hélène Frappat, Trois films fantômes de Jacques Rivette: Phénix suivi de L’An II et Marie et Julien (Paris: Cahiers du cinéma, 2002), 11.

- Frappat, Trois film fantômes, 19.

- Dalle Vacche, Diva, 1.

- I have written previously about Rivette’s taxi-dance hall aesthetic in “Re-staging the Feminine in Jacques Rivette’s Haut bas fragile,” Studies in French Cinema 1.2 (2001): 98-107 and also in “Reenvisioning Genres,” Jacques Rivette (Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 77-98.

- Francis Steegmuller, Cocteau: A Biography (Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1970), 263. Steegmuller affirms that it was Wiener’s music that had attracted Cocteau to the Gaya, which would become his anti-Dada headquarters during the 1920s. The Gaya would ultimately become known as Le Boeuf sur le Toit. Rivette would undoubtedly have been aware of Wiener’s affinity for American jazz, which had led to the pianist’s connection with Cocteau, and also his stature as a composer. Wiener composed films scores for many French directors, including Jean Renoir, Julien Duvivier, Jacques Becker, Robert Bresson, Marcel Herbier, and Marc Allégret.

- Robert Ferguson, Henry Miller: A Life (London: Hutchinson, 1992), 79.

- Paul G. Cressey, The Taxi-Dance Hall: A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1932), 232.

- Cressey, 241.

- Cressey, 97.

- Cressey, 7.

- Albert Camus, L’homme révolté in Œuvres Complètes1 (Paris: Gallimard, 1983), 77.

- James Naremore, Acting in the Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 147.

- Renate Günther, “Gender and Sexuality,” Marguerite Duras French Film Directors Ser. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002): 96-133. See also, Leslie Hill, Marguerite Duras: Apocalyptic Desires (London: Routledge, 1993).

- Günther, 119-120. See also, Marguerite Duras, India Song, trans. Barbara Bray (New York: Grove Press, 1976). In the play, India Song, Duras provides these written stage directions: “Voices 1 and 2 are women’s voices. Young. They are linked together by a love story. Sometimes they speak of this love, their own. Most of the time they speak of another love, another story. But this other story leads us back to theirs. And vice versa,”

- Maurice Darmon, Le cinéma de Marguerite Duras: La Trilogie Anne-Marie Stretter Tome 2: 1974-1976 (Paris: 202 Éditions, 2015), 40.

- Jacques Aumont, L’attrait de l’oubli (Paris: Éditions Yellow Now, 2017), 34.

- Aumont, 34.

- Leslie Hill, Marguerite Duras: Apocalyptic Desires (London: Routledge, 1993), 37, 38.

- See Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Rivette’s Rupture (Duelle and Noroît),” Chicago Reader (February 28, 1992). http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2016/09/rivette-s-rupture/. Rosenbaum discusses Duelle and Noroît as marking a transition between “the modernism of his first six features and the postmodernism of his last six.” See also Adrian Martin, “The Broken Trilogy: Jacques Rivette’s Phantoms,” Lola 6: Distances (September 2015). http://lolajournal.com/6/rivette.html

- Marguerite Duras, Le Navire Night, Césarée, Les Mains négatives, Aurélia Steiner, Aurélia Steiner, Aurélia Steiner (Paris : Mercure de France, 1979), 14-15. Duras’s final film was Les Enfants (1985); however, she affirms her intent to return to writing books in 1979 in the preface to the script of Le Navire Night: “The end of cinema. I was going to write books again, I was going to return to my native land, to that terrifying labour that I had left behind ten years ago.” (Cinéma fini. J’allais recommencer à écrire des livres, j’allais revenir au pays natal, à ce labeur terrifiant que j’avais quitté depuis dix ans.), 14-15.

- Jacques Rivette, “Scenes from a Parallel Life: Jacques Rivette Remembers,” interview by Karlheinz Oplustil, 4 May 1990, Paris. In The Jacques Rivette Collection. DVD Box Edition. Arrow Academy, 2016.

- Marguerite Duras and Jacques Rivette, “Sur le pont du Nord un bal y est donné: Un Dialogue avec Marguerite Duras et Jacques Rivette,” Le Monde (March 25, 1982), 15.

Note: All translations are my own unless otherwise noted.