V.F. Perkins

Acting on Objects

1. Stella Dallas (King Vidor, USA, 1937): Stella and the Bow Tie

In the first fifteen minutes of Stella Dallas, we are given an effective sketch of the forces, desires and delusions that propel the abrupt marriage in 1919 between small-town millhand’s daughter Stella Martin (Barbara Stanwyck) and factory manager Stephen Dallas (John Boles). Then the film whips us forward past the birth of a daughter, Laurel, for an equally deft account of the resentments and irritations that nag away at the pair now that familiarity has dulled their first hopes and fervours. Stephen, exiled from the wealth and position of his Long Island upbringing, is vexed by his wife’s defiant and incorrigible coarseness, while Stella chafes under his pedantic efforts to reform her speech and manners.

All this is dramatised in a scene at Millhampton’s country club. To Stephen’s disgust, Stella resists those concessions to decorum that would stand in the way of a good time. The sequence ends with Stephen impatient to leave but thwarted, stuck holding his wife’s coat while she dallies in unsuitable company.

On the dissolve, the club’s dance band music fades into a quiet where our ears pick up even the click of a light switch. It must have been a sombre journey that brought the couple back to their apartment. Stephen paces the hallway searching for the words that will express his discontent but contain his fury. Stella breaks the silence and stands at the door of her dressing room[1] . She feigns resignation to the ‘usual lecture’, having asked – disingenuously – ‘What have I done this time?’ Mr. Dallas opens the inventory of his wife’s offences against good taste and his authority. Reproofs and protestations are exchanged until Stella retreats to her dressing table and begins the removal of her jewellery. She takes off trinket after trinket, announcing her indifference with a hostile glance as Stephen advances to stand over her and complete the catalogue of his concerns. But her mood changes as she responds to Stephen’s challenge to consider the crucial matter: ‘What’s to become of us?’ Her hands are arrested at the clasp of her necklace and her eyes lift to meet Stephen’s gaze. Her voice softens on the words ‘Yes, Stephen.’ Notably it is Stella’s attitude that changes here, not Stephen’s. He remains fixed in position to ask ‘Stella, why did you marry me?’ – a question that is fraught with accusation, and a cover for the one that must bother him most.

Stella answers the question in more ways than one. In words: ‘Because I was crazy about you, silly, and I still am, only…’ In the tone of her speech: no longer argumentative but conciliatory, even a mite playful. But also in gesture: as she speaks she relaxes into a brief smile and reaches up to undo Stephen’s bow tie. A cut to a shot favouring Stephen directs our attention to Stella’s hands pulling the tie apart and preparing to deal with his collar[2]. Removing her sparklers, Stella had set about undressing. Releasing his neckwear, she has set about undressing Stephen. The action carries such weight, for Stella and for us, that everything surrounding it is charged with meaning. Most remarkable, by contrast with the mobility of Stella’s hands and their effect on his dress, is the rigidity of Stephen’s posture and the fixity of his gaze. He has no response at all to Stella’s touch, and seems not to notice the invitation that her gesture implies.

The bow tie enables Barbara Stanwyck to declare Stella’s sexual availability with intimate indirectness while blocking all suggestion that the move is prompted by the character’s own appetite. Her gesture is not extended with any further intimations of desire. We may gather that Stella wishes to dissolve Stephen’s annoyance and is relying on the one approach that has always, till now, been effective. We recognise that the failure of her offer marks a turning point. It is certainly, for her, an immediate disappointment. She has rested her arms on Stephen’s shoulders (in an answering shot with subtly softened lighting) while beginning a plea for understanding. But Stephen interrupts her, without dilution of his hectoring manner, to resume the declamation of his sorrows and grudges.

Stella’s arms sag. ‘Yes, Stephen’ she says, this time in tones of defeat and dejection[3]. She abandons her work on the bow tie and turns away to attend once more to her necklace. Perhaps she has noticed Stephen’s repossession of the word ‘crazy’, draining it of erotic meaning. ‘Once a long time ago’ he charges, ‘you said you were crazy to learn everything, become someone, didn’t you?’ The death of Stephen’s sexual interest in Stella is definitive. Incapable of being aroused, he is too locked in to his discontents even to observe that an offer has been made. Through all further discussion he stands with the wings of his tie dangling unattended from his collar, the limp remnant of a bid unanswered.[4] His self-righteous protestations of love are rendered hollow. The rest of the sequence presents developments pivotal for the plot: Stephen’s (how long withheld?) announcement of his promotion to a post in New York, Stella’s refusal to move there with him (on the terms he has laid down) and her lack of concern at the separation thus decreed. But we understand the motives that underlie each turn of these events because we have witnessed the action and inaction centred on a single item of costume.

2. Johnny Guitar (Nicholas Ray, USA, 1954): Emma and the Chandelier

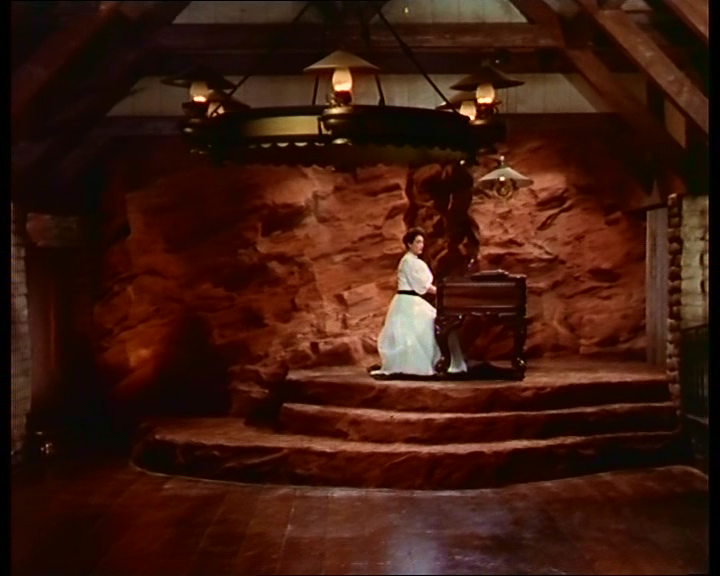

In the elaborate architecture of Johnny Guitar one piece of furniture draws the most particular attention, and may have done most to give the picture its aura of the baroque: the outsized oil-lamp chandelier that illuminates the public area of the gambling saloon erected in the wilderness by the heroine, Vienna ( Joan Crawford). More at home in a cathedral (where it would be called a corona) than in a barroom,[5] this wonderfully crafted ornament hangs as the symbol of Vienna’s most anomalous ambitions and claims. Largely unspecified acts of corruption and self-abasement have financed her rise and the construction of an establishment that she hopes will make her secure and wealthy, if she can survive the hostility of the locals lead by a cattle baron McIvers (Ward Bond) but more determinedly by her antagonist, Emma Small (Mercedes McCambridge).

If Vienna has traded honour, as she laments, for ‘every board, plank, and beam in the place,’ then this gorgeous fitment represents quite an investment of shame. But it represents Vienna also in her aim to exchange virtue for splendour. Other articles too – patterned china, a bust of Beethoven, a baby grand piano – offset the liquor barrels, the craps table and the roulette wheel by providing a dressing of refinement to fill out the spaces and decorate an otherwise gaunt structure. Vienna’s is to serve dual functions; it must deliver profit to a saloon-woman capitalist while making a home for one who seeks recognition (her own, most of all) as a lady of culture. The culture will make the lady.

Now chandeliers like this are a familiar item in Western decor, often helping to paint the barroom in the colours of a bordello. Props departments must have been able to offer them in many designs and sizes. What distinguishes Johnny Guitar is the prominence the object is given in the image and in the action. (It is not once mentioned in the dialogue.) Its functions have to have been written into the script and It is often cheated into position so as to occupy the upper foreground of the frame[6]. On separate occasions, when lowered on its rope by Johnny and when hauled aloft by Vienna, its weight is displayed to us and made audible in the effortful click of the ratchets. The episode to which it gives a spectacular climax begins with an overhead shot as Vienna circles it, taper in hand, to light each of its six lanterns. The care we see lavished on it gives us the sense that it is an art object particularly cherished as a token of Vienna’s achievement and her aspiration.

Having been given so strong a feeling for what the object means to Vienna, we are well placed to apprehend its meaning for her enemy. Emma Small sees Vienna as an intruder who has brought a contagion of vice so potent, so dressed up in glamour that it cannot be contained and can only be wiped out along with its source. Emma is further convinced that she alone sees this truth with the force and clarity to drive effective opposition. She implicates Vienna in robbery and murder so as to turn a town posse into a lynch mob with Vienna as its main quarry.

Vienna has closed the saloon and redefined it as her private sanctuary, but Emma leads the men to violate its space and drag its owner off to hang. The exit from the saloon is choreographed with the power and finesse in a single shot that sweeps everyone out through the building’s one entrance, binding many jarring energies into one deadly flow. The momentum is further propelled by the malign thrust of Victor Young’s music. But as the last few of the invaders reach the doors the camera ceases to track their movement. It pauses within to observe the last departure. The orchestra holds its breath until Emma trips back in, alone and newly armed with a shotgun almost as big as she is. She smiles inwardly, knowing what to do, as the first thing she sees in the deserted saloon is the chandelier. We are given it from her viewpoint and, for the first time, in close-up.

That image is extended, as are the ones that follow, to capture Emma’s savouring the moment. She cocks the shotgun, then grins wide-mouthed and lifts it into firing position. The image teases with readability as Emma discharges her erect, borrowed weapon into the round of Vienna’s chandelier. But it is the fulfilment of hatred that brings Emma such joy and wonder. In performance McCambridge identifies Emma first with the chandelier, bowing low with it as it crashes to the floor, then with the awful power of light shattered into flame. A crazy glee enraptures her and she stretches out her arms to urge on the spread of the blaze. She looks with wonder on the fire that will purge her world of saloon-women and everything they stand for. Backing away to rejoin the hanging party, she is glued to the spectacle and holds the swing doors wide apart to feast her eyes as long as she can.

The speechless mania enacted here is a necessary complement to the shrewdly calculated rhetoric with which Emma, the politician, has earlier inflamed the posse. (The duality of her character mirrors the duality of Vienna’s.) There’s a further marvel of performance a few seconds away, but it projects Emma’s delight in the results of her action rather than in the action itself. What about the chandelier?

It gives Emma a destructive means to a destructive end[7]. It gives the film and the actress the means to display Emma’s pleasure in the process of destruction as well as in its outcome. We do not know just how spontaneously she decided on the deed. (Unlike the lynching, it is not something she has advocated.) She may have been nurturing the event in fantasy ever since the first of Vienna’s boards, planks and beams was set in place. Fire is the most promising agent for the ruination of a mainly wooden structure. Setting the blaze allows Emma a part in the eradication of her foe that is hers alone, whereas the gallows-work is an essentially communal procedure. But if all that’s wanted is a fire, the options are many. A box of matches will do. If the chandelier is to serve, the desired effect may be achieved – we have been shown – by releasing the rope that holds it in place. But that would require effort; the act would be more strenuous than playful. Shooting it down, with one blast, imbues the action with the masculine potency specially attached, in the Western, to gunplay.

But most vital is the way that the assault on the chandelier draws on and sustains the sense that the bond of hatred between Vienna and Emma gives each of them peculiar insight into the other’s psyche. (It could be the other way also – that their insights fuel their hatred.) Living delightedly with Johnny Guitar over many years I have been persuaded that the unacknowledgeable intimacy of hero[ine] and antagonist is a prime source of the dramatic power that allows extremity of emotion to survive and harmonise with the movie’s continuous play with absurdity. Emma has neither seen nor been told anything that suggests what significance the chandelier holds for Vienna. But without this, she knows (and does not have to think about it) that to bring down this chattel is to annihilate Vienna’s own emblem of her achievement and her hopes. Not having to think about it goes for us, too. At this crisis we understand the motives that underlie each action and gesture because we have absorbed the meanings invested in a single item of decor.

V.F.Perkins was a founding editor of Movie magazine and is a member of the editorial board of its on-line successor, Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism. Honorary Professor in the Film and Television Studies department that he created at Warwick University in England, he is the author of Film as Film (Penguin, 1972) and of monographs in BFI Film Classics series, on Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1999) and Jean Renoir’s La Règle du jeu (2012).

[1] This has also to be the bedroom, though no bed is seen.

[2] A striking instance of the way that cutting, as well as visual organisation, can define the burden of a movie image. The shot’s length is governed by the duration of the gesture. As soon as the action is completed, the shot changes.

[3] The repetition here, like the adjacent one on the word ‘crazy’, is one of many gifts bestowed on the actors by expertly crafted dialogue. It is noteworthy that the screenplay was the work of a team who were husband and wife: Sarah Y. Mason and Victor Heerman.

[4] Imagine the range of possible meanings of Stephen’s action if he were at any point to complete the removal of his tie. When and how he did this would matter greatly, it’s clear.

[5] For confirmation see http://www.rouge.com.au/5/perkins.html

[6] It is able to be on screen often because Philip Yordan’s screenplay locates so much of the drama in the public space of the saloon. The first part of the movie is skilfully constructed to yield thirty minutes of continuous action in this setting.

[7] This is a formulation I was delighted to be offered by a student in a long-ago seminar.