Brandon De Wilde* : “Eloquent of Clean, Modern Youth”

Murray Pomerance

Accustomed to seeing platoons of good-looking adolescents marching through blockbuster adventure stories (to name only a few, Emilio Estevez and company in The Breakfast Club [1985] and other denizens of the John Hughes world, Leonardo DiCaprio in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape [1993], Jake Lloyd in Star Wars: The Phantom Menace [1999], Natalie Portman in Léon: The Professional [1994], Asa Butterfield in Hugo [2011]), contemporary viewers of film might be interested to know that through the end of the 1970s Hollywood cinema produced relatively few movies in which there were significant parts for young people; and further that only a handful of child and teen actors became well known for their screen work. Beyond Jackie Coogan (The Kid [1921]), Shirley Temple (Bright Eyes [1934]), Judy Garland (The Wizard of Oz, Babes in Arms [both 1939]), Mickey Rooney (A Midsummer Night’s Dream [1935]), Roddy McDowell (How Green Was My Valley [1941]), and Dickie Moore (Little Men [1934], Sergeant York [1941]), who worked in the early days of the “golden age,” we can count in this group Johnny Crawford (El Dorado [1966]), Tommy Rettig [The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T [1953]), Hayley Mills (The Parent Trap [1961]), Darryl Hickman (Leave Her to Heaven [1945]), Patty McCormack (The Bad Seed [1956]), Christopher Olsen (Bigger Than Life and The Man Who Knew Too Much [both 1956]), and Brandon De Wilde.

Born April 1942 in Brooklyn, to a Dutch-English-Huguenot French father (related to Eugène Delacroix) who had a career as actor (he worked with Tallulah Bankhead in The Little Foxes and appeared as well in five other shows including Brother Rat and in numerous television programs) and an English-Scottish former-actress mother (who had performed in Tobacco Road), Brandon was something of a child prodigy in performance. His career was launched with vigor in the Broadway run of Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding (January 5, 1950 – March 17, 1951), where he played the starring role of John Henry West beside Ethel Waters and Julie Harris and under the direction of the legendary Harold Clurman (who thought him an “enchanting” boy [264]). The De Wildes were living in Baldwin, Long Island, and Brandon’s father Frederic (Fritz) was stage-managing Member on Broadway. His friend Terry Fay, the casting director, knew the boy and suggested Fritz “bring his son in for an interview. Brandon’s parents were anything but anxious to have their child in show business. They kept postponing the interview in the hope that a child actor would be uncovered to play the important role”:

When the De Wildes could no longer stand answering the phone requests they finally brought Brandon in to see Producer [Robert] Whitehead. He looked the boy over and then asked the father, “Can he act?” “I don’t know,” was the honest reply. But Whitehead decided the lad looked the part so perfectly that he urged Fritz to let Brandon read for the role. Unhappily, the parent took his son home to study up on a scene which was to be read the next morning. He rehearsed the disinterested youngster that night. The next morning, Brandon awakened his Dad and recited the entire scene from memory—not only his own, but Miss Waters’ part as well.[1]

As John Henry, Brandon was precociously charming, thickly bespectacled, curious about everything the adolescent Frankie (Harris) and her mammy Berenice (Waters) had to say about trauma, rejection, and being alive. Rarely was he off the stage, lurking in corners, perched upon the table, posing in Frankie’s clothes, asking far too pertinent questions, all with a bravura display of confidence and poise. In 1952, when Stanley Kramer produced a film version with Waters and Harris, under the helm of Fred Zinnemann, Brandon was again cast, but now his tour de force performance had an indelible place onscreen, so much so that he came to the wider attention of Hollywood. There are numerous provocative and deeply touching moments with John Henry in the film, among which are his almost successful cheating at cards, his cooing adoration of Frankie’s outlandish dress for her brother’s wedding, his querulous musing on mortality (“What’s ‘die’?”), and a perfectly evocative gesture late in the film when as Berenice—who has one glass eye—comments on seeing something with her mind’s eye De Wilde stands beside her, takes her face in his little hands, gazes down into it, and asks, “Berenice—which one is your mind’s eye?” in his slightly shrill, exceptionally articulate voice; the voice that never stops questioning, the voice that can never be told enough, a voice especially evocative, perhaps, as with Waters and Harris he sings the hymn, “His Eye is on the Sparrow.” Waters dubbed him “a perfect gem”[2], and Zinnemann recollected “a lovely little boy, completely professional and self-disciplined and with a wry sense of humor; everyone was charmed by him.”[3] If Bosley Crowther found the screen John Henry “delightfully mettlesome and humorous” but “lanky in the legs”[4] Brooks Atkinson two years earlier praised the script as “masterly” and allocated Brandon De Wilde’s stage performance a paragraph of its own:

Brandon De Wilde, who is 7 ½ years old, plays the neighborhood boy with amazing imperturbability. This is a vastly humorous part, and Brandon won all the hearts in the audience last evening, for he is resourceful and self-contained; and Mr. Clurman, who has a special gift for the parts of children and young people, has staged these interludes tactfully and amusingly.[5]

To both stage and screen De Wilde brought a certain palpable innocence coupled with a directness and physical attractiveness that could be variably modeled depending on narrative needs, much as would a major star but already at his very young age. “He never missed a performance, doing the play for 572 performances on Broadway and 56 times on the road from Chicago to the West Coast . . . His father turned to stage managing to have ‘time to look after Brandon.’”[6] In the film, some of De Wilde’s gestures, sharply articulated, were plotted into the background; yet cinematographer Hal Mohr’s precise lighting plan always picked him out, and Mohr assisted his performance further by shooting with Garutso balanced lenses, a favorite of Kramer’s, which focused light of plural wavelengths. Even with wide apertures and figures in near focus there resulted a sufficiently deep focus to bring distinct clarity to John Henry, wherever he was in the shot.

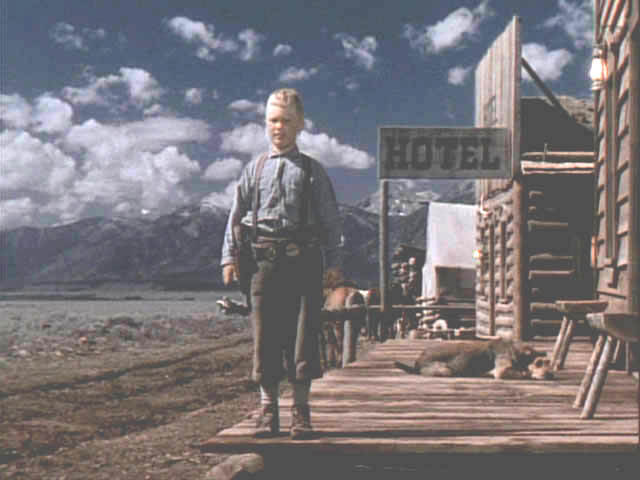

A year after the Zinnemann film, and sporting a Dutch-style bowl cut, the boy was working for George Stevens in Wyoming and at Paramount studios in the role that more or less seeded his career (and became iconic in the history of American film), that of Joey Starrett in Shane. Again that querulous, high-pitched voice—“Shane? Shane? Come back, Shane!!”; again the young boy looking up at his favorite adult as an icon of truth and purity; again the sense of little Brandon as a curious kitten, jumping all over the place and tucking himself into corners so that he doesn’t miss any of the action: the perfect stand-in for the camera, and thus the ideally childlike, keenly perceptive representative of the viewing audience. It was easier for people watching the Technicolor Shane than for even the eagerest viewers of the black-and-white Wedding to see and admire Brandon’s platinum blond hair and sharp, glittering sky-blue eyes. His behavior with Van Heflin and Jean Arthur in this film is so naturalistic, so spontaneous that it is difficult to conceive of them as other than his real parents. Bosley Crowther writes that Brandon shows “a very wonderful understanding of the spirit of a little boy amid all the tensions and excitements and adventures of a frontier home.” De Wilde’s performance seems to make the film cohere for this critic, who after ceding him a full paragraph—

As a matter of fact, it is the concept and the presence of this little boy as an innocent and fascinated observer of the brutal struggle his elders wage that permits a refreshing viewpoint on material that’s not exactly new. For it’s this youngster’s frank enthusiasms and naïve reactions that are made the solvent of all the crashing drama . . . And it’s his youthful face and form, contributed by the precocious young Brandon De Wilde, that Mr. Stevens as director has most creatively worked with through the film.[7]

–waxes on about how the performance gives moments “the keenest punctuation” and proceeds, after praising Heflin, Arthur, Alan Ladd, Jack Palance, and a number of other character players including the prodigious Emile Meyer, to this rare exclamation: “But it is Master De Wilde with his bright face, his clear voice and his resolute boyish ways who steals the affections of the audience and clinches ‘Shane’ as a most unusual film.”[8]

Brandon De Wilde, (left) bright-eyed in the morning as Joey, and (right) a surrogate viewer in Shane (1953).

As to the bonding between Joey and Shane (Ladd), it is a celebrated token of 1950s screen interaction. When (with puppy at his feet) Joey calls after Shane, the name “Shane” not only rhymes with “pain” but becomes a perfect metonym for suffering and redemption in the reddening sunset. For this performance, Brandon De Wilde became the youngest actor ever to receive an Academy Award nomination. (Palance was also nominated, but the award went to Frank Sinatra for From Here to Eternity.)

The actor’s “coming of age” film, as it were, was Philip Dunne’s Blue Denim (1959), during the filming of which he celebrated his seventeenth birthday and saw “emergence from childhood both as an actor and as a person”[9] (Brand 4). It was a time in his life when he was beginning to experience and value independence. A publicity release offered that his room in the De Wildes’ West 86th St. apartment

is furnished like a den: twin couches instead of beds. He has a built-in hi-fi set, his own record player, built-in book-cases. The walls are sand color, there’s a gold rug, the couch covers are greenish-velvet with vari-colored throw pillows, and, in tribute to his status as a young adult, he has his own telephone in his room—the basic rate being paid by his parents, anything over by Brandon from his allowance.[10]

He was openly opinionated about the proper behavior for teenagers on dates (holding a point of view that by today’s standards would seem modest if not downright prudish: he wants “looks—but something deeper . . . when you get to be 17 [you] look for something more, personality”; further, “If I meet a girl—I bring them home”[11]). Johnny Mathis recordings wowed him, as did the writing of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, “roast beef, steak, hot dogs and Chinese food,” baseball, and The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), not to mention his role models, Helen Hayes, Paul Newman[12], and Marlon Brando, whose surname became his nickname.[13]

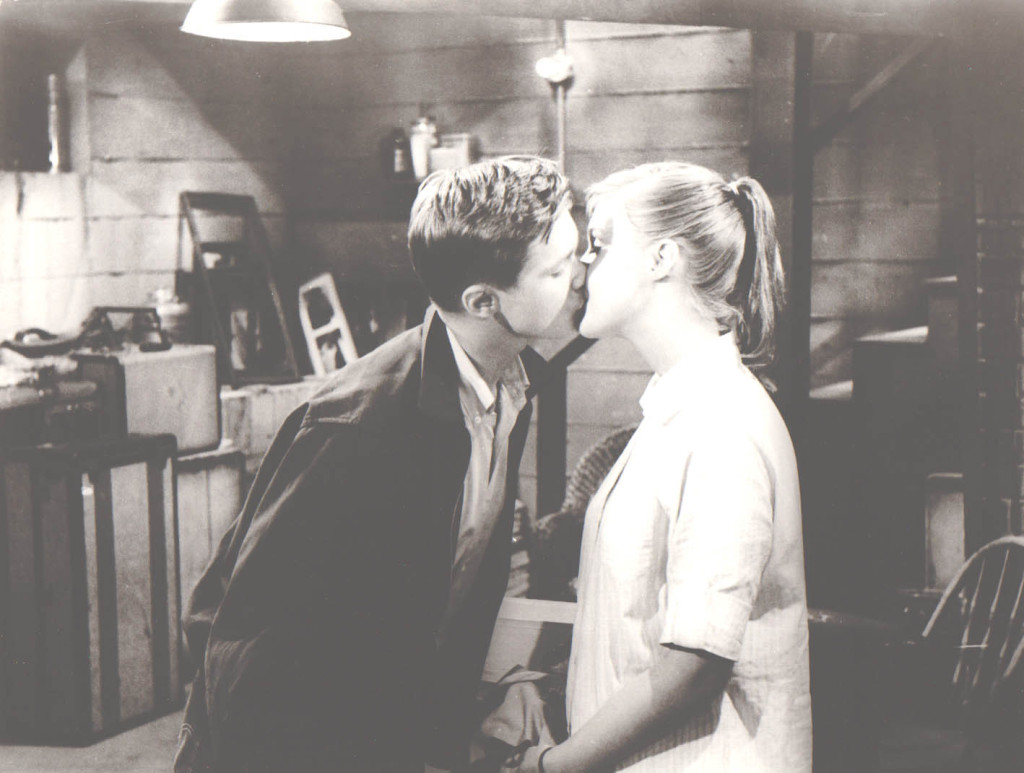

Blue Denim is conceived as a portrait of the conventional teenager par excellence but it is worth saying that this creature is not, in the mid-to-late 1950s, the rebel typified by the young Elvis, or James Dean, or Brando. Arthur Bartley is wholehearted, well-scrubbed. He has sense enough to be embarrassed in front of his parents, furtive about his smoking, card-playing, and drinking with his outspoken chum Ernie (Warren Berlinger) in his basement den. In a telltale scene, the two boys climb downstairs, open up some beers, and proceed to a poker game, but not until Ernie has done a sweet imitation of Paul Henreid’s cigarette-lighting routine from Now, Voyager (1942), lighting two fags in his mouth and letting sweet Arthur choose one for himself. De Wilde puffs emphatically, putting on a gangster show: not only is Arthur breaking loose from his parents here but the actor beneath is breaking away from his child shackles in Shane, The Member of the Wedding, and other juvenile roles. The two tough-talkers are interrupted by pert, well-meaning Janet (Carol Lynley) who ends up in a hesitant clinch with Arthur on the comfy old sofa. She confesses she doesn’t like to see him the way he is when Ernie’s around, all bluster. “It’s easier to put on an act,” says he. “Arthur,” says she, “Anybody who looks at you right off, they say, ‘There’s a somebody.’” Something is building on his face as he paces around the dark space. “Can I . . .?” “No,” Janet whispers, “it’s no good if you ask.” So they just kiss, and on the soundtrack the violins go momentarily crazy. “Our noses got in the way,” he smiles. Outside in the street she pretends to stumble at the kerb, so that he will step forward and she can grab him and kiss even harder. For De Wilde, it’s still an adventure in chastity, but he has crossed the border—in more ways than one, since off-camera, and through a chemistry never explained – the style of the time – Janet is pregnant.

Right of passage. Arthur (Brandon De Wilde) and Janet (Carol Lynley) in their getaway in Blue Denim (1959).

The tentative and frustrated sexuality on display in this scene was characteristic of most adolescent relationships in the generally repressive 1950s, with curious and miscomprehending adults always inhabiting the margins of the space where teenagers could interact feelingfully. While much Hollywood teen melodrama has centralized transgressive figures—Vic Morrow in The Blackboard Jungle (1955); Corey Allen or Sal Mineo in Rebel Without a Cause (1955); Brando in The Wild One (1953)–teenage life, rife with hungers and titillations, remained for most kids essentially orderly, chaste, and moralistic. Brandon De Wilde as the good boy in difficult situations was a realist middle-class icon. In one scene, Janet is in Arthur’s basement den discussing his sexual knowledge, which he leads her to surmise is substantial. “I’m glad,” says she, approaching him, but he flees to a dark corner and throws himself helplessly and ashamed onto the sofa. She runs over. “I never, either,” he admits, with keylight washing over his unblemished face, “I made it all up about other girls. I don’t know anything.” This portrayal, raw without being uncivilized, was precisely the sort to alienate young men eager to feel and display self-assurance in a similarly virginal state (so that the “naughty,” “improper” characters played by such as Clift, Brando, Dean, Allen, and Morrow could more easily have attracted them); Brandon’s was as powerful and revealing a portrait of conventional youthful masculinity at the time as has been put to the screen, pungent especially in his very clear–and very clearly suspended and unrealized–hunger. Arthur finally sacrifices his future as an architect or lawyer to go off dutifully with Janet as, Bernard Herrmann’s strident score finally coming to harmonic rest, the film ends. De Wilde’s coming of age fell flat with Crowther, who, forgetting that a young man finding his competence lacks grace and skill, ruefully found him only “amateurish and wooden.” Pointing unconsciously to the dense repression the actor was brilliantly reflecting, the critic said Arthur “seems not to comprehend the reason for his predicament.” I take this as an unwitting compliment to Brandon’s acting skill, because it’s only looking back — as John Knowles noted in A Separate Peace —that we understand. Behind the camera, now five feet eight inches tall and weighing 145 pounds, Brandon was eagerly dating Carol Lynley.

In John Frankenheimer’s All Fall Down (1962) and Martin Ritt’s Hud (1963), the now matured De Wilde played curiously matched roles, but in two radically different keys, because one film’s domesticity is urban, protected (even a little smothered), and suffering from fractures of personality while the other’s is rural, unbounded, and suffering modernity’s rupture of agrarian value. In William Inge’s screenplay for All Fall Down (from a James Leo Herlihy novel) Brandon is Clinton, younger brother to Berry-berry Willart (Warren Beatty), a dissolute, shiftless, promiscuous drifter. The boy’s nagging and intrusive mother (Angela Lansbury, in her second maternal role for Frankenheimer that year) and alcoholic-genius father (Karl Malden) have little time for, or curiosity about, Clint beyond probing his journals to see what he is writing all the time. The boy aims to be a novelist and is always somewhat withdrawn from the action, scribbling about a world we never see, except when a female visitor (Eva Marie Saint) captures his heart and when he is off with his brother, gazing at that Apollonian icon with an “adulation [he] cannot shade in his wondering, trustful eyes.”[14] It is only at film’s end that Clint’s bated breath seems to run out, Berry-berry’s craven abusiveness becoming too plain to neglect and Clint finally walking away from him to get on with his life. Before this moment, Berry-berry has been “a fetish and talisman of hope and perfection that the boy clings to in anxious desperation.”[15] De Wilde’s performance is simple and true, deep and shockingly accurate.

Top: Clint (Brandon De Wilde) and Mom (Angela Lansbury) in All Fall Down (1962); Below: Brandon De Wilde, always writing, in All Fall Down (1962).

Reflecting in 1966, De Wilde estimated Frankenheimer the director he liked the best:

He’s really a wonderful guy. We got along beautifully. And all he ever said to me before a scene was . . . well, first he’d take me over in a corner, away from everyone, drop an arm around my shoulder and say, “Listen, kid, just get in there and beep-beep the bonk-bonk out of that bang-bang scene.” We really got along well. He’s really a swell guy.[16]

The youthful admiration is dulled and the youthful gaze harder and more resolute with De Wilde’s Lonnie Bannon in Hud (from a novel by Larry McMurtry). The older figure here, Paul Newman in the eponymous role, is Lon’s uncle, still one more promiscuous drinker straying from the ruts of traditions trod out by his aging, worn-down father (Melvyn Douglas) on a cattle ranch in Texas. But Lon is devoted to his grandfather as persona and protector and to the value system for which he stands, based on nature’s cyclicity and imbricated with a deep respect for the land that is one’s trust. While Hud, “a nineteen sixties specimen of the I’m-gonna-get-mine breed—the self, snarling smoothie who doesn’t give a hoot for anyone else” would like to sell the ranch for oil rights, old Homer, “the aging cattleman who finds his own son an abomination and disgrace to his country and home”[17] will have none of it, and Lon is his stalwart helper, the next generation to whom he is bequeathing his knowledge, feeling, and reason even as the catastrophic Hud has connived in legal fact to inherit the property. When Homer collapses and dies one night at roadside, it is Lon who cradles him in his arms, with wide eyes drawing in every last syllable of hope and education from the man he intends to emulate. Hud is sullen and quiet, counting the minutes until his father is history and the world is fully his. In the end young Lon avoids going to Homer’s funeral, packs his bag, and leaves the ranch forever. “Brandon de Wilde is eloquent of clean, modern youth,” wrote Crowther, “naïve, sensitive, stalwart, wanting so much to be grown-up.”[18] (The same “wanting . . . to be grown up” is palpable in Blue Denim, but Crowther had no taste for watching it in a boy so callow.)

Lon (Brandon De Wilde) with Hud (Paul Newman) at Homer’s death in Hud (1963). Digital frame enlargement.

De Wilde gave fifty-six television performances in the twenty years after 1951, including a 1962 stint on “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” and a star turn as the eponymous orphan hero in the 1953-54 series “Jamie.” Among his other film appearances, he stars with James Stewart in James Neilson’s Night Passage (1957) and plays the pivotal role of John Wayne’s fated son Jere Torrey in Otto Preminger’s In Harm’s Way (1965).[19] In the latter film his scenes with Wayne are striking for their maturity and strength, coming as a resolution of De Wilde’s long apprenticeship as the innocent child or young brother looking upward to see which way he should go. This father neither likes nor approves of him, yet the young man has a stony sense of dignity and pride, a prodigious grace, and finally a staunch morality as he faces the knowledge that his fiancée has suicided after being raped by a senior officer. The New York Times found him “crisp and cocky.”[20]

At 3:25 p.m. Mountain Time on July 6, 1972, driving to visit his new wife in the hospital, Brandon De Wilde’s camper van collided with a guard rail near the intersection of Kipling Avenue and the Grand Army of the Republic Highway in Lakeview Colorado. He died that night at the age of thirty.

Murray Pomerance is Professor in the Department of Sociology at Ryerson University. He is the author of numerous books, including the forthcoming Marnie from BFI Film Classics, as well as the recent The Eyes Have It: Cinema and the Reality Effect, Alfred Hitchcock’s America, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema, The Horse Who Drank the Sky: Film Experience Beyond Narrative and Theory, and Johnny Depp Starts Here, among many other books on film, edited volumes, and works of fiction.

* With sincere thanks to Steven Rybin and Jesse De Wilde. Brandon’s name is credited as de Wilde in his childhood and De Wilde in later years, but in several signed photographs I have seen, he spelled it “deWilde.”

[1] Harry Brand, Undated Biography of Brandon de Wilde, Brandon de Wilde file, Jane Ardmore Papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills, 2-3.

[2] Ethel Waters (with Charles Samuels), His Eye Is On the Sparrow: An Autobiography, New York: Doubleday, 1951, 274.

[3] Fred Zinnemann, An Autobiography (London: Bloomsbury), 1992, 114.

[4] Bosley Crowther, “Stanley Kramer’s Production of ‘The Member of the Wedding’ Has Premiere at Sutton,” New York Times (31 December 1952), 10.

[5] Brooks Atkinson, “At the Theatre,” New York Times (6 January 1950), 26.

[6] Harry Brand, Undated Biography of Brandon de Wilde, 3.

[7] Bosley Crowther, “Stanley Kramer’s Production,” 10.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Harry Brand, Undated Biography of Brandon de Wilde, 4.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Anonymous, Unsigned notes on Brandon De Wilde, Jane Ardmore Papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills.

[13] Harry Brand, Undated Biography of Brandon de Wilde, 5-6.

[14] Murray Pomerance, “Ashes, Ashes: Structuring Emptiness in All Fall Down,” in Murray Pomerance and R. Barton Palmer, eds., A Little Solitaire: John Frankenheimer and American Film (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 188.

[15] Ibid., 189.

[16] Bob Ellison, “Brandon de Wilde Still Boy in ‘Shane,’” Los Angeles Times (22 April 1966), 1.

[17] Bosley Crowther, “ ‘Hud’ Chronicles a Selfish, Snarling Heel,” New York Times (29 May 1963), 26.

[18] Ibid.

[19] For further discussion, see Murray Pomerance, The Eyes Have It: Cinema and the Reality Effect (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2013), 166-174.

[20] Bosley Crowther, “John Wayne Starred in Preminger Film,” New York Times (7 April 1965), 36.