Animals in Korean Cinema: From Absent Referent to Present-Day Predicament

David Scott Diffrient

Why do we look? What do we see? How do we respond?”

— Randy Malamud, An Introduction to Animals and Visual Culture

In his recently published study of the ways in which human representations of nonhuman animals in visual culture have long contributed to the latter’s objectification and exploitation, Randy Malamud poses a series of provocative questions about the literal and figurative “framing” of interspecies encounters in film.[1] For decades, movie audiences have grown accustomed to the presence of animals onscreen, through a “cultural frame” that often takes those creatures—be they domesticated livestock or undomesticated wildlife—out of their natural habitat. Rarely, however, does the spectator ever pause to reflect on his or her own ethically dubious relationship to the cinematic image or, more broadly, to the anthropocentric nature of a medium that transforms animals’ material reality into a symbolic language suited for human consumption. Besides foregrounding and even fetishizing animals’ instrumentality as sources of either aesthetic pleasure (e.g., trilling songbirds, shimmering goldfish), nutritive protein (e.g., egg-laying chickens, dairy cows), physical labor (e.g., plough-pulling oxen, homing pigeons) or companionship (e.g., canine and feline pets), filmic representations can be said to box in nonhumans within the quadrilateral “cage” and artificial “ecosystem” of individual shots, which are generally composed with humans (rather than “lesser” beings) in mind. Malamud argues that, instead of merely taking for granted the animal as a culturally caged entity—as a being whose very “being-ness” or autonomous existence has largely been denied by the medium’s anthropocentric tendencies—viewers should ask themselves why they are looking at such images in the first place, and what actually constitutes the object of their gaze.[2]

Notably, the author’s rhetorical invitation to the self-reflective spectator, who is asked to adopt a different “way of seeing” and at least entertain the idea of a creaturely subjectivity outside the orbit of man’s consciousness, recalls the title of John Berger’s essay “Why Look at Animals?”[3] The latter text, which is part of the art critic’s 1980 collection About Looking, uncovers the paradoxical manner in which animals—once the center of our existence—have been culturally marginalized through ever-more visual representations. One need only consider the preponderance of animal imagery within contemporary children’s culture, as part of the design and/or content of particular consumer items (e.g., toys, games, picture books, clothing, etc.), to recognize how diffusion often leads to disposability or disappearance.[4] In being reduced to spectacle, which ironically suggests hypervisibility, nonhuman beings are rendered invisible – a vanishing act performed by postindustrial man so as to gain even greater dominion over the beasts that once safeguarded yet threatened his forbearers’ existence (as both food and foe). The natural extension of that tendency to treat animals as spectacle, observable in everything from commercial goods to academic paintings, is the wholly unnatural space of the public zoo, a site of “enforced marginalization” where captured creatures from distant lands stand in for other spoils of colonial conquest (including people). Put on public display (ostensibly to satiate the visitor’s desire for knowledge, much like a museum artifact might) and physically isolated from others of their own (or different) species, the zoo animal becomes “utterly dependent upon [its] keepers.”[5] Moreover, and most crucially for Berger, a fundamental change in the nature of interspecies looking accompanies this cultural and material shift in human-nonhuman relations, with the once-unmediated gaze between the two figures drifting into, rather than across, a “narrow abyss of non-comprehension.”[6]

In this short essay, I do not presume to point a way out of that abyss of non-comprehension so much as offer a further substantiation of Berger’s main arguments. Building upon his claim that “the essential relation between man and animal was [and continues to be] metaphoric,” and assuming that the latter figure lies at the very origins of the former’s symbolic language (which can be traced back to the earliest cave paintings), I wish to explore some of the most persistent yet overlooked tropes in a national context where animals are paradoxically omnipresent and invisible. Specifically, a brief look at onscreen depictions and spoken references to animals in Korean cinema will reveal their multi-purpose malleability as all-too-handy metaphors for a range of social issues that have plagued the East Asian peninsula both before and after its 1948 division into North and South sovereign states. Although greater attention will be given to South Korean motion pictures in which animals are rhetorically invoked as “absent referents” (an expression that Carol Adams introduced in her 1990 book The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory), I gesture toward pre-division cultural productions that laid the foundation for future representations, in terms of their mobilization of nonhuman beings as reductively allegorical figures. Of course, the incorporation of animal-based metaphors in Korean cinema echoes earlier modes of representation discernible within the country’s literary output and folkloric traditions (a history beyond the purview or scope of the present study). But the international popularity of the motion picture medium makes it especially noteworthy as a source of transcultural or “universal” values as well as conventionalized notions of what animals might “mean” to contemporary audiences.

Why, some readers will ask, should one focus on Korean cinema, as opposed to any other national context or type of cultural production in which animals are mobilized as metaphors? Surely many of the observations that emerge in the following pages can just as easily be applied to motion pictures from other regions of the world. What makes the Korean case so striking is the relative absence of critical discourse surrounding human-nonhuman relations in film and the contrasting plethora of commentary (in journalistic accounts and academic essays) about animal rights and animal welfare – hot topics in a country where the much-discussed consumption of dog meat and the continued harvesting of bear bile (despite governmental crackdowns) have attracted international attention.[7] The conspicuous lack of writing about the country’s cinematic bestiary merely exacerbates the absence of the animal as “absent referent,” even as Koreans themselves have demonstrated, through their actions and words, a growing awareness of the plight of creatures whose needs have often been deemed secondary to those of humans.

Significantly, filmmakers have been at the forefront of recent efforts to raise public consciousness and to promote the South Korean government’s newly enforced legislation designed to protect the wellbeing of animals. Chief among them is Yim Soon-rye, director of such critically lauded Korean New Wave films as Three Friends (Sechinku, 1996) and Waikiki Brothers (Waikiki beuradeoseu, 2001), and producer of the animal-rights-themed omnibus film Sorry, Thanks (Mihanhae, komaweo, 2011), which brings together the individual contributions of four filmmakers (including her own short “Cat’s Kiss”).[8] Despite its diverse range of cinematic styles (a common complaint leveled against multi-director episode films), the latter film displays thematic consistency in its approach to the lives of canine and feline pets and is just one of the many independent productions to have been featured at the Animal Film Festival, an annual event launched in the southern city of Suncheon in 2013. Sorry, Thanks is also a film that, like Bong Joon-ho’s more high-profile Netflix production Okja (2017), has been adopted by nonprofit organizations and advocacy groups like Coexistence of Animal Rights on Earth (CARE), International Aid for Korean Animals (IAKA), and Korea Animal Rights Advocates (KARA) in the hopes of affecting change at the institutional level and in the hearts and minds of movie audiences at home and abroad. Significantly, Yim has served as the Executive Director of KARA for several years, illustrating the strong affinity between independent filmmakers and rights activists who share a commitment to ending animal testing, dog meat consumption, factory farming, and other exploitative or cruel practices that have long colored the global (mis)perception of South Korea as a land where speciesism—or, the prejudicial privileging of humans over nonhumans—runs rampant.

In the following pages, rather than explore the current landscape of Korean animal rights activism, I highlight a cross-section of older films that demonstrate the need to pursue this topic—the ethical implications of cinematic speciesism—further, in lengthier, more robust studies than mine. Indeed, this essay is but a prelude to the more astute philosophical treatises on human-nonhuman relations in South Korean cinema that are surely forthcoming. Regardless, my hope is that the present study draws attention to the peculiar salience of animals in the Korean cultural context and amplifies Malamud’s claim that media representations reproduce an asymmetrical power dynamic discernible within the society at large, through the “inherently biased,” tilted privileging of human agency over nonhuman malleability. Indeed, the ease with which animals are shaped into allegorical figures in Korean films underscores the need to be ever-vigilant as spectators ethically attuned to their largely unheard calls.

From Sweet Dream to A Pig’s Dream: Classic Cinematic Imaginings of the Animal

In the animal world we find metaphors for the full range of human emotion.

— Marc R. Fellenz, The Moral Menagerie: Philosophy and Animal Rights

As is the case with other nations’ film industries, the cinema of South Korea has had a complicated and troubled relationship with animals since the motion picture medium’s origins as a technological curiosity after the turn of the twentieth century. One of the oldest surviving films from the colonial era, director Yang Ju-nam’s early Chosun talkie Sweet Dream (Mimong, 1936), is the first of many motion pictures to call upon the symbolic suggestiveness of nonhuman creatures as a kind of cinematic shorthand—a convenient, if also reductive, means of revealing aspects of human characters that might otherwise remain undisclosed traits of their personality or temperament. Tellingly, the first shot of this recently discovered film, following its title card and opening credits, shows two chirping birds inside a cage. [FIGURE 1] Framed against the sky and dangling from a string that is tied to the roof of a middle-class home, the birdcage sways in the breeze, rocking back and forth as the shot holds on this image of gentle commotion for six seconds. In retrospect, this metal object and its feathery occupants, which are given pride of place in the narrative, can be seen as a portent of the disturbance that will play out in the opening scene, set inside that minimally furnished yet well-appointed house.

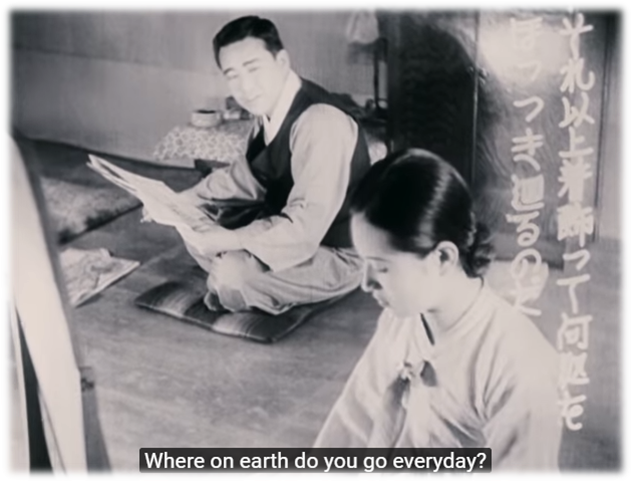

A husband and wife, Seon-yong and Ae-soon, sit quietly apart from one another on the floor, but the silence is soon broken when the former asks the latter (who is busy applying makeup) if she is going somewhere. [FIGURE 2] When Ae-soon responds, “to the department store,” Seon-yong complains about her frequent shopping. This initiates a domestic spat that ends when the petulant woman, who threatens divorce, leaves in a huff. Before she departs for the shopper’s paradise of Seoul, Ae-soon sarcastically tells her overbearing husband that he should lock her up in a room if he wishes to confine her to a life of housekeeping and childrearing.“But I’m not a caged bird,” she says, bringing verbal confirmation to what the audience has already surmised about this modern, materialistic woman, who resists the cage-like domesticity that has been foisted upon her through the institution of marriage. When he asks, “How can a human being say such a thing?” she responds with her own rhetorical question: “Are you saying that I’m not even a human?” Such dialogue, while heavy-handed (in keeping with the film’s melodramatic mode), links the rhetorical figures of the animal and the human, just as the composition and juxtaposition of individual shots indicate director Yang’s equally obvious use of visual symbols—specifically, the birdcage—as nonverbal commentary on the state of this bickering couple’s relationship.

Figures 1 and 2: The 1936 film Sweet Dream (Mimong) begins with a shot of birds inside a cage, followed by a similar image of domestic confinement involving the female protagonist, Ae-soon.

Although it is a feature-length motion picture, Sweet Dream clocks in at a brisk forty-eight minutes, making the reappearance of the birdcage in subsequent scenes all the more glaring as the film’s principle allegorical object. At the midpoint of the film, after Seon-yong forces his cheating, shopaholic wife out of their house (calling her both a “slut” and an “animal”), he stumbles upon their teenaged daughter, Jeong-hee, crouched in a pool of tears and lamenting the absence of her mother. As he tries to comfort the girl, who yearns for long-withheld maternal affection, the birdcage swivels in the breeze behind them, once again reminding us that the winged creatures and their own cramped home are to be read as an analogous emblem of female confinement. Indeed, this shot seems to suggest that Sweet Dream’s most resonant theme now encompasses multiple generations of women who struggle against patriarchal, parental, and even (offscreen) colonial authority in early twentieth-century Korea. Although artfully composed, the shot focuses so much attention on the cage that its feathery occupants figuratively “disappear,” or cease to have any autonomous presence as anything more than a metaphor for the human condition.

Equally noteworthy is the birdcage’s third appearance in the film, presented as a sudden, unexpected insert shot during a chaotic scene in which Ae-soon’s new boyfriend—a shady gangster who has just robbed a hotel—is attacked by rival members of Seoul’s criminal underworld. Flashing onscreen for three seconds, the avian enclosure, which remains tethered to the place where it was first shown in the film (i.e. far away from the hotel room where the fight breaks out), bobs violently, as if the brutal events in one distant location are impacting life back at home. The shaking birdcage not only symbolizes the familial discord that we have witnessed up to that point, but also foretells the calamitous injury that soon befalls Jeong-hee. In typical melodramatic fashion, with an emphasis on cruel fate, the young girl is suddenly hit by the speeding taxi that spirits her mother to yet another romantic tryst (this time with a ballet dancer whom Ae-soon has fallen for, and who is shown boarding a departing train in the film’s penultimate scene). Although Jeong-hee survives this vehicular collision, Ae-soon, now repentant, takes her own life at the hospital bedside of her recuperating daughter, lending a darkly ironic final twist to the film’s title. As in many of the melodramas that would follow this motion picture’s 1936 theatrical release, the female protagonist is made to pay the ultimate price for her misdoings, her yearning for a life of hedonistic pleasure and self-fulfillment outside the domestic sphere. However, the woman’s death, at least in this early motion picture (in which the cage can also be read as a symbol of Japan’s disciplining apparatus during the colonial era), is emotionally resonant in a way that is not extended to her “animal other”—the birds whose own metaphorical annihilation is not lingered upon or milked for the audience’s emotional gratification.

In his brief analysis of the film, Han Sang Kim notes that Sweet Dream, which was sponsored by the Seon Man (Chosun-Manchuria) Traffic Times for the purpose of providing audiences with instructional guidelines about traffic safety, “reveals a striking contrast between trains and automobiles.”[10] But it also reveals a sharp dichotomy between human and nonhuman animals. Despite the apparent comparability between the film’s female characters and the birds, the latter are merely props within a prop (the synecdochal cage, which itself mimics the enclosure of the frame), reduced to being a functional signifier lacking subjectivity. In this way, they are no different from the caged birds that would appear onscreen twenty-five years later, in director Yu Hyun-mok’s Golden Age classic Stray Bullet (Obaltan, 1961).

Near the half-hour mark of this film, a young war veteran named Yeong-ho accompanies a military nurse-turned-factory worker named Mi-ri (an old friend with whom he has recently become reacquainted) back to her apartment. On the way up, they stop on the top steps to consider how small the world below them seems, and how curious it is that an old man should be dozing in the courtyard outside her flat. As the man, whom they refer to as “Heaven’s Gatekeeper,” snores away, two chirping birds flutter above his head. [FIGURE 3] Contained within a cage, these winged yet flightless animals are offered up by director Yu as an objective correlative to the pair of young lovers who are each trapped in the existential malaise and socially debilitating environment of a soulless city.

Tellingly, the most overt, symbol-laden commentary about Yeong-ho’s depressed psychological state comes from his own lips, when he tells a group of friends that, for the past two years, he has failed to find a job. But he does so indirectly, by way of animal metaphors. At the beginning of that lengthy speech, the unemployed vet compares his mounting frustrations—his personal and professional struggles—to “fighting a wild bear.” As he extends that figure of speech into a humorous anecdote, Yeong-ho explains that he went from hunting a bear to chasing after a boar and then going after a deer, all to no avail, before setting his sights on something more attainable: a pheasant. When that too eluded him, he tried to catch a rabbit, but found only more hunters (i.e. job competitors) in search of that “animal.” He concludes his talk with yet another reference to nonhuman creatures, telling his listeners that, in order to succeed in a competitive job market, they should be like crows, the only birds that ironically are not afraid of scarecrows.

Figure 3: Two chirping birds flutter above the head of “Heaven’s Gatekeeper” in director Yu Hyun-mok’s Stray Bullet (Obaltan, 1961).

While none of the aforementioned animals actually appear onscreen in this or any other scene of Stray Bullet, they are rhetorically invoked or brought to virtual life as “absent referents,” to borrow the words of Carol Adams, an ecofeminist critic who has noted the tendency in anthropocentric fictions to treat nonhumans as metaphors for describing the experiences of human characters.[11] Akira Mizuta Lippit, author of Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife, likewise draws attention to cultural representations that trade on the transversality of animal and metaphor. As he states, “the animal is already a metaphor, the metaphor an animal. Together they transport to language, breathe into language, the vitality of another life.”[12] Thus, when a litany of animal references spills from Yeong-ho’s lips in the abovementioned scene, all of which are employed to explain his lack of employment, this seemingly powerless figure ironically exerts his linguistic mastery or power over voiceless “others” – creatures whose selfhood runs a distant second to the primary focus on human life in this and practically all films, Korean or otherwise. In this way, motion pictures, even those like Stray Bullet that depict the harsh realities and unequal power structures of a classist society, or which seek to dismantle various discriminatory –isms (e.g. racism, sexism, etc.) in an ethically responsible way, leave unexamined the framework of speciesism that undergirds most representations. That framework, the cultural theorist Cary Wolfe claims, has made it nearly impossible to reverse the “fundamental repression” of nonhuman subjectivity “that underlies most ethical and political discourse.”[13]

According to Adams, the absent referent of the animal “is both there and not there.” “It is there through inference,” she explains, “but its meaningfulness reflects only upon what it refers to because the originating, literal, experience that contributes the meaning is not there.”[14] Absence doubles in the case of those films that were made before 1936’s Sweet Dream, especially those like director Na Un-gyu’s Arirang (1926) that, in the words of Kyung Hyun Kim, mobilized socially resonant “visual allegories” in order to bypass Japanese film censorship. Footage of “cats and dogs fighting each other,” which is said to have been included in this lost classic of early Korean cinema, could be interpreted as a symbolic figuration of anticolonial resistance, surreptitiously snuck in to the narrative discourse by a filmmaker who famously took part in the national independence movement, but who resorted to metaphor-driven subterfuge in order to make a political point. If contemporaneous viewers understood the hidden meaning of Na’s animals, effectively “seeing” what could not be shown (and which can no longer be seen, since Arirang has been lost to time), they did so at the expense of the creatures themselves, who are “there and not there,” the lowliest of the low in the “human-centered hierarchy” of cultural representations.[15]

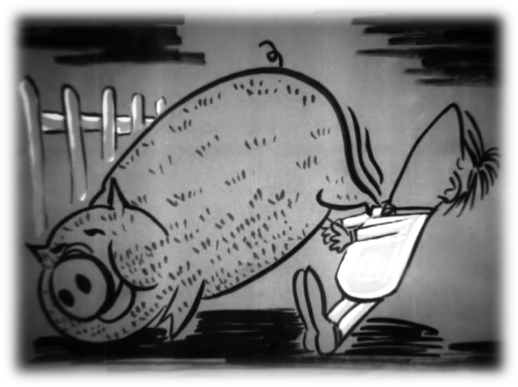

Within months of Stray Bullet’s theatrical release, another film critical of the growing social divide between the wealthy and the poor—director Han Hyeong-mo’s A Pig’s Dream (Dwaejikkum, 1961)—placed even greater emphasis on animals as symbolic and literal currency in the lives of Koreans who, pushed to the margins, resort to shady dealings in order to scrape by. As the female narrator intones in this film’s opening montage, which shows documentary footage of the traffic-choked streets of Seoul, a housing shortage has forced millions of people to seek shelter along the outskirts of the capital city. At this point, Han juxtaposes shots of an impoverished shantytown with starkly contrasting images of luxurious homes. The voiceover continues to set the scene, informing the audience that the government’s Department of Social and Health Services has built thousands of residential dwellings outside of Seoul for selected families (i.e., those that are able to pay a monthly rent), and that one such family will be the focus of A Pig’s Dream. Notably, the titular animal appears during the opening credits, which are superimposed atop a hand-drawn title card showing an enormous hog looming over a filmmaker. We then see the pig grinning cartoonishly as it kicks another person in the neck, an action that hints at this film’s broadly comical tone as well the cruel misfortune that eventually befalls Son Chang-su and his wife by narrative’s end. [FIGURES 4 and 5]

Figures 4 and 5: The title sequence of Han Hyeong-mo’s A Pig’s Dream (Dwaejikkum, 1961) shows a cartoon pig acting petulantly before the camera.

Although its title can be read in two ways (either as someone’s pig-related dream or, more fancifully, as the dream of a pig), the film soon makes it clear that the animal who appears in the opening credits is merely the object (rather than subject) of an anthropocentric fiction, and certainly not an autonomous being with an interior life or imagination of its own. We first encounter the main character, Mr. Son, as he is roused from sleep one morning by his impatient wife, who has grown tired of his proclivity for alcohol and their ongoing financial worries, which come to a head each month when the government bill collector, Mr. Chun, pays a visit. Chang-su is unusually excited this morning, telling his wife he had “the type of lucky dream that only comes once in a lifetime.” Although several different creatures, from snakes to swallows, can be interpreted as signs of good fortune if encountered in a dream, the pig occupies a special place in the minds of many Koreans, the most superstitious of whom will sometimes buy lottery tickets upon waking from such a reverie.[16] The protagonist likewise believes his dream to be a good omen, but Mrs. Son (who has her hands full with their precocious son, Young-jun) is not so easily convinced, and opts to use this pig reference as an opportunity to comment sarcastically on her husband’s rotundness. Eventually, though, she too begins to shed her pessimism, a change of heart triggered by a neighbor’s offering of a free pig as potential money-maker and problem-solver for this lower-middle-class family. The neighbor’s hidden motive—getting her daughter into Dongkwan middle school, where Mr. Son works as a teacher—is soon revealed after Mrs. Son puts aside her concern about the bad odors associated with pig-raising and agrees to accept her gift. As their conversation comes to an end, Mrs. Son, now brimming with optimism, sends her housemaid Soon-ja to go fetch the pig from her neighbor’s house, an order that the younger woman misinterprets as a sign that she will need to sharpen her knife (in anticipation of eating pork cutlets).

Before Soon-ja shows up with the pig, another visitor arrives unannounced. Mr. Kim, the protagonist’s old friend from Busan, descends from a repurposed jeep along with a stranger named Charlie Hong. As a second-generation Korean living in Hawaii, Charlie is involved in some nefarious activities, smuggling pharmaceuticals into the country and helping his associates get rich in the process. He claims to be on the crew of an American transport ship that docks in Busan Harbor every few months. Each time it does, the oily man “brings some medicine from the U.S.” and has Mr. Kim “sell it for cheap.” They have travelled to Seoul, the latter claims, because the latest shipment was so large. As these are “extra medical supplies,” this is not a case of smuggling, Charlie insists, luring the initially skeptical protagonist into a scheme that will eventually result in his and his wife’s complete loss of what little money they have. Thus, the black pig that arrives in the following scene, once seen as a portent of the wealth awaiting this increasingly desperate family, in retrospect seems to have augured their ultimate downfall, leaving them not only penniless but also childless. In the film’s tragic dénouement, they learn that Young-jun, upset at the man who robbed his parents, went out looking for Charlie only to get hit by a car. That ending, eerily reminiscent of the aforementioned scene in Sweet Dream (when the female protagonist’s young daughter is nearly killed by a speeding vehicle), reveals A Pig’s Dream to be the melodramatic tragedy that it really is – a generic inversion of the tone established in the cartoonish opening credits and in early scenes depicting the comical misadventures of this family on the literal and figurative outskirts of South Korean society.

With the possible exception of director Kim So-Dong’s Money (Don, 1958), which similarly hinges on a scene in which an animal (specifically, a cow) is sold out of financial necessity, no other film of its day puts as much emphasis on money as this 1961 production. Nearly every scene in A Pig’s Dream features dialogue revolving around the presumably better life that Mr. Son and his wife might have should they ever get any money. As the social ethicist Chai-sik Chung has written, those areas of Korean society “that traditionally have been governed by other values than money,” including the family, friendship, child-rearing, and education, “have been subjugated to ruthless market-oriented reasoning, economic calculus of costs and benefits, and to the dealings for hire and sale.”[17] Chung’s diagnosis of a problem that has only worsened in recent years, leading to the depersonalization of social services and the fraying of social bonds in twenty-first-century South Korea, could be applied with only slight modification to the finance-fixated characters and impoverished milieu on view on A Pig’s Dream and other films of the late 1950s and early 1960s (a period of rapid industrialization, one of the reasons for the tremendous growth of cities like Seoul). “You need money to live,” Charlie tells Mr. Son before the swindler’s fraudulent identity is revealed. “Money is number one,” the American continues before concluding that not having any cash-flow “is the same as slitting your throat.”

The death that is alluded to in this scene, and which occurs near the film’s conclusion, in fact looms over the entire text, especially after the pig arrives. When two of Mr. Son’s friends show up for an afternoon drink, one of them tells him that the animal will make “the perfect appetizer.” Similarly, when Mr. Chun, the government bill collector, darkens their doorstep in the following scene, he mutters “donkkaseu” (the Korean word for “pork cutlet”) upon glimpsing the pig, which effectively is being denied a right to happiness for the sake of filling human bellies. [FIGURE 6] Although it is the family’s son, rather than the precariously situated pig, who eventually dies, the latter’s disappearance in the film’s third act is disturbing in its own right, seeing as how central the animal had been to their hopes for success. At one point, Mr. Son informs his alcohol-drinking pals that “this pig is our future,” and indeed so much narrative and thematic weight is placed on the shoulders of this overdetermined signifier—a metaphor laden with too many meanings—that it is effectively crushed, rendered invisible.

Figure 6: The titular animal in A Pig’s Dream is referred to by one character as “donkkaseu” (the Korean word for “pork cutlet”).

In fact, for all its apparent centrality to this film’s premise and themes, the titular animal is just one of many nonhuman creatures invoked in A Pig’s Dream, the opening montage of which explains to the audience that, unlike snails, people in Seoul “can’t carry their homes on their backs.” While “birds can still build homes” in the city, as the female narrator informs us over images of nests in trees, there simply isn’t enough land for flightless humans to do so. Later, during Mr. Son’s first meeting with Charlie, Mr. Kim tells him that, “If pharmaceutical brokers get word” of their medical cargo, “they’ll be like bees to honey.” Significantly, he says this while a clock in the shape of an owl (hanging from the wall of the main character’s tiny living room) tick-tocks away. [FIGURE 7] This last object, a material metaphor given its own close-ups whenever director Han Hyeong-mo feels the need to underscore the theme of time slipping away from the family, might remind us of John Berger’s claim that, in their hypervisibility as transfigured commercial goods, animals as actual/embodied creatures have all but disappeared.

Figure 7: A conspicuously framed clock in the shape of an owl: one of the many animal references in A Pig’s Dream.

Here I am reminded of the pivotal scene in yet another 1961 Korean film, Kang Dae-Jin’s postwar classic The Coachman (Mabu), when the horse being drawn by the aging male protagonist is sideswiped by a jeep on a narrow city street. [FIGURE 8] Rather than dwell on the physical damage dealt to the animal, who would likely be euthanized in such a situation, the film focuses attention on the injury sustained by Chun-sam, the main character, whose “surplus status in the industrializing, capitalist South Korean economic landscape,” according to Kelly Jeong, is exacerbated after his tragic fall.[18] Unable to take care of his children any longer once his main source of income has been removed (ironically at the hands of his own boss, the coach owner who drove the vehicle that hit the horse), Chun-sam is “reduced to the status of a child.”[19] But that social descent is nothing compared to the damage done to the film’s only equine character who, though prominently featured on The Coachman’s paratextual materials (posters, advertisements, etc.), becomes an absent referent in the literal sense of being erased from the text following the traffic accident, never to be seen again.

Figure 8: The ill-fated horse in director Kang Dae-Jin’s 1961 film The Coachman (Mabu).

High Ideals and the Lowliest of the Low

Many of the above ideas could be summed up by the renowned rights advocate Joan Dunayer, who states, “Nonhuman animals occupy oppression’s deepest level.”[20] In her book Animal Equality: Language and Liberation, Dunayer notes that derogatory metaphors in the English language, such as the use of “cow” to denote a dull, fat woman and “pig” to denote either a male chauvinist or someone who lives filthily, “rely on speciesism for their pejorative effect.”[21] Besides encouraging injustice toward humans (“especially those who belong to vulnerable groups”), such negative images work to maintain the hierarchical order of things, further subjugating animal groups whose typical behaviors are grossly distorted in the process (e.g., pigs, in actuality, are not “filthy” creatures). Of course, hackneyed expressions circulate in the Korean language as well (e.g., cheong gaeguri, or “blue frog,” denotes a person “who always does things the opposite way he or she was told to do,” yeo-u, of “fox,” denotes a calculating female who gets what she wants, and neukdae, or “wolf,” denotes predatory male with a dirty mind). But such sociolinguistic constructs need not be verbally communicated in a cinematic text when there are so many other signifying tools at the filmmaker’s disposal to register analogous states between human and nonhuman animals. Elements of mise-en-scène, such as lighting, set design, and staging, as well as cinematographic and editorial factors (ranging from the composition of shots to their side-by-side juxtaposition), contribute to the meaning-making process, and can be harnessed to prompt the kind of symptomatic readings illustrated above.

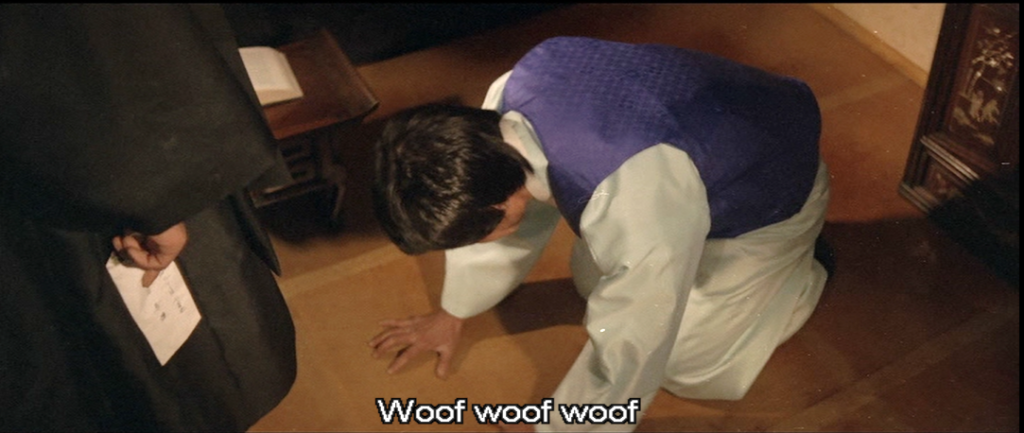

Although no cats or dogs appear in director Kim Ki-young’s 1978 adaptation of Yi Kwang-su’s 1932 novel Soil (Heulk), one man is forced by another to adopt the demeanor of a domestic animal after he has been caught romancing the latter’s wife. [FIGURE 9] Barking like a dog, Gap-jin assumes a canine-like position before the film’s protagonist, Heo-sung, a former houseboy-turned-lawyer who exerts his newfound power over his male rival (whom he refers to as being “lower than a beast”) by subjugating him in a manner that anticipates a similar scene in Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy (2003). Fans of this action-packed neo-noir will recall the moment in question, when the title character—an emotionally and physically wounded man named Dae-su, who is coming to grips with his unwitting complicity in the death of a former classmate’s sister years earlier—lowers himself before his “master” like a dog, licking Woo-jin’s shoes.

Figure 9: In several Korean films concerning power imbalances between members of different social classes, characters assume a “canine” position, barking in a subservient fashion, as in Ki-young’s Soil (Heulk, 1978).

Such scenes of humiliating behavior, premised on the widely accepted notion that to be a nonhuman is to be “below” or “less than” a human, have filtered into South Korea’s popular unconscious for decades, as further evidenced in director Lee Jang-ho’s award-winning film A Fine, Windy Day (Barambuleo joheun nal, 1980). Significantly, the lowly social status of this film’s three main characters, Deok-bae, Chun-sik, and Gil-nam, is partly conveyed through canine references. This includes an early scene (immediately following the opening credits) in which one penniless member of the trio of workers, Deok-bae, sneaks onto the property of an upper-class family in the Gangnam area in search of food scraps, but is chased away by a snarling dog whose bark he soon begins to imitate. [FIGURE 10] Full of sound and fury but signifying little beyond his “lack, insufficiency, and incompleteness” (a general condition of Korean masculinity in films from that period of rapid urban development, according to Kyung Hyun Kim),[22] Deok-bae’s bark is directed not toward the dog but rather toward the property owners, who laugh haughtily from their elevated perch.

Figure 10: One of several canine references in A Fine, Windy Day (Barambuleo joheun nal, 1980).

The idea that animals “fall below humans in a natural hierarchy” has been an entrenched part of the Western philosophical tradition since the time of Aristotle, who argued that animals lacked the faculties needed to reason and therefore could be appropriately used as “resources for human purposes.”[23] This “subordination thesis,” introduced by the Greek philosopher and subsequently supported by theologians of the Middle Ages such as Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, has since become the dominant strain of thinking, reinforced through Judeo-Christian teachings that maintain that “God created humans in his own image.”[24] As David DeGrazia points out, philosophers such as Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke contributed to the entrenchment of the Aristotelian thesis that human beings can and should claim supremacy over lesser beings. But they went even farther in claiming that animals lacked the attributes that distinguished humans, including “a capacity for language and innovative behavior,” which were outward signs of an interior state. Most cinematic representations of animals subscribe to this idea by repeatedly emphasizing their functional usefulness to humans and by denying any inkling of a deeper consciousness that might give lie to several centuries’ worth of received wisdom about these so-called lesser beings. In doing so, a majority of films—Korean films in particular—privilege instrumentality over interiority and perpetuate a speciesist ideology that has only recently been challenged or deconstructed by activist cultural producers.

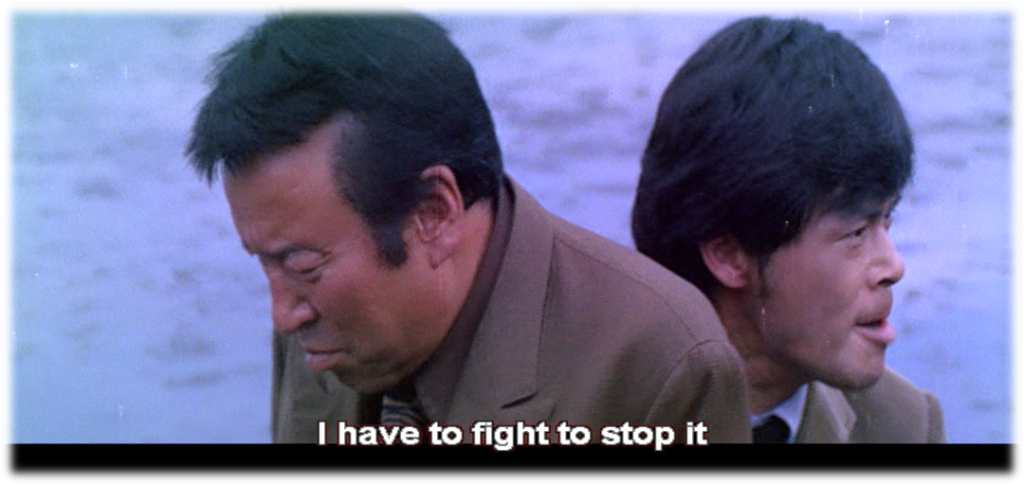

Although properly activist forms of cinematic discourse have circulated in South Korea at least since the days of the Minjung Movement in the early 1980s (albeit often through underground or alternative channels of non-commercial distribution), the welfare of animals is still a relatively new topic. It is worth pointing out, though, that as early as 1977, the subject was superficially broached in auteurist and genre productions, including that year’s Iodo. Directed by maverick filmmaker Kim Ki-young one year prior to the release of his previously mentioned adaptation Soil, this bizarre mashup of supernatural horror, murder mystery, and social problem cinema includes a lengthy subplot involving loss of aquatic life resulting from environmental pollutants. [FIGURE 11]

Figure 11: Kim Ki-young’s Iodo (1977) focuses on a reporter who witnesses the deaths of abalone and other sea creatures on the titular island.

When the ill-fated protagonist, a reporter who witnesses the deaths of abalone and other sea creatures on the titular island, brings this information to his boss at the local newspaper, the latter character responds by saying that, yes, “there are many issues to deal with.” Poisonous chemicals dumped into the water by factory workers is one problem, but so too are farm insecticides, which “are killing all the honey bees,” and air pollution, which indiscriminately claims the lives of all creatures, the older man proclaims. Although Iodo should be applauded for acknowledging human culpability in the harming of wildlife, and for foregrounding the ethical imperative to “fight for the cause” of animal welfare (which the reporter commits himself to), the film ultimately trivializes political activism by showing a man, mad with hysteria, devolving into broadly comical theatrics, as when he runs wildly toward a nearby factory that he plans to “sabotage.” [FIGURE 12] The fruitlessness of that endeavor, combined with the fact that the scene that immediately follows his foolhardy venture shows him sitting across from his boss at a restaurant with a plate of steaming barbeque beef placed between the two men, is indicative of the limitations of cinematic discourse in treating animal rights with the seriousness that the subject deserves. Moreover, the protagonist’s activism is initially triggered when he considers what the death of countless fish might mean to his own livelihood as a fish farmer, a profession that he is then forced to give up in pursuit of a newspaper job. Thus, self-interest motivates what appears to be socially engaged crusading, and the lives of animals are cheap in all but the most literally economic or transactional of senses.

Figure 12: In a way that anticipates contemporary examples of animal activism in Korean cinema, Iodo acknowledges human culpability in the harming of wildlife and foregrounds a character who commits himself to fighting for nonhuman welfare.

I could point toward numerous other examples of the problematic ways in which animals are reductively represented and harshly treated in Korean cinema; from the slaughterhouse scenes in Lee Seong-gu’s Ilwol: The Sun and the Moon (1967) (a Golden Age film about a family of butchers), to the emphasis on harvesting bear bile in the same director’s Where the Buckwheat Blooms (Memilkkotpil muryeop, 1969) (another classic adaptation, this time about a group of itinerant peddlers going from market to market with their ever-dependable horses and donkeys), to the casual violence directed against a dog in The Quiet Family (Joyonghan gajok, 1998) (in which the canine is kicked brutally by the family’s patriarch while they feast on food). The fact that this scene from director Kim Ji-woon’s pitch-black comedy, which prompts laughter from the offscreen yelp of the abused dog, has largely been overlooked by critics provides further evidence that a different way of looking at Korean cinema is needed if animals are to be granted the respect or level of attention that we lavish on human characters. As such, it is high time to embrace or seek out a new, nonhuman hermeneutics to account for the precarious place of animals in film; an “animanalysis,” if you will, that—similar to theorist Anat Pick’s notion of “creaturely poetics” (which frames the “shared embodiedness of humans and animals”)[25]—recognizes multiple forms of personhood in its pursuit of a more thorough assessment of textual and thematic material.

David Scott Diffrient is Professor of Film and Media Studies in the Department of Communication Studies at Colorado State University. His articles have been published in Asian Cinema, Cinema Journal, Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television, Journal of Film and Video, New Review of Film and Television Studies, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, and other journals as well as several edited collections. He is the author of Omnibus Films: Theorizing Transauthorial Cinema (Edinburgh University Press) and the co-author of Movie Migrations: Transnational Genre Flows and South Korean Cinema (Rutgers University Press). He recently served as the co-editor of the Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema.

Notes

[1] Malamud, 5-7.

[2] Malamud, 6.

[3] John Berger, About Looking (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 1-26. See also: Margo DeMello, Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-Animal Studies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 9-11.

[4] Berger, 14, 20.

[5] Berger, 23.

[6] Berger, 3.

[7] For more on these subjects, see: Anthony L. Podberscek, “Good to Pet and Eat: The Keeping and Consuming of Dogs and Cats in South Korea,” Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 65, no. 3 (2009): 615-632; Atsuko Ichijo and Ronald Ranta, Food, National Identity and Nationalism: From Everyday to Global Politics (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 137-139; and Victor Watkins, “Bear-Aware for Twenty Years,” in Lisa Kemmerer, eds., Bear Necessities: Rescue, Rehabilitation, Sanctuary, and Advocacy (Boston, MA: Brill, 2015), 41-42.

[8] Besides Yim’s own contribution “Cat’s Kiss,” Sorry, Thanks includes short films directed by Park Heung-sik (“My Younger Brother”), Oh Jeom-gyoon (“Chu Chu”), and Song Il-gon (“Thank You, I’m Sorry”).

[9] Marc R. Fellenz, The Moral Menagerie: Philosophy and Animal Rights (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2007), 14.

[10] Han Sang Kim, “My Car Modernity: What the U.S. Army Brought to South Korean Cinematic Imagination about Modern Mobility,” Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 75, No. 1 (February 2016): 63–85.

[11] Carol Adams, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory [25th Anniversary Edition] (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015), 53

[12] Akira Mizuta Lippit, Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 165.

[13] Cary Wolfe, Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 1.

[14] Adams, 22.

[15] Adams.

[16] Terry Stocker, The Paleolithic Paradigm (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2009), 506-507.

[17] Chai-sik Chung, The Korean Tradition of Religion, Society, and Ethics: A Comparative and Historical Self-understanding and Looking Beyond (New York: Routledge, 2016), 149-150.

[18] Kelly Jeong, “Nation Rebuilding and Postwar South Korean Cinema: The Coachman and The Stray Bullet,” Journal of Korean Studies, Vol. 11, no. 1 (2006): 136.

[19] Jeong.

[20] Joan Dunayer, Animal Equality: Language and Liberation (Derwood, MD: Ryce, 2001).

[21] Dunaver.

[22] Kyung Hyun Kim, The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 34.

[23] David DeGrazia, Animal Rights: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 3.

[24] DeGrazia, 4

[25] Anat Pick, Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and Film (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011).